Alan Montague, RMIT University; Alan Nankervis, RMIT University; John Burgess, RMIT University; Nuttawuth Muenjohn, RMIT University; Ros Cameron, Australian Institute of Business, and Timothy Bartram, RMIT University

Over the next decade up to 40% of jobs could be replaced by automation. That’s according to a forecast from the Committee for the Economic Development of Australia.

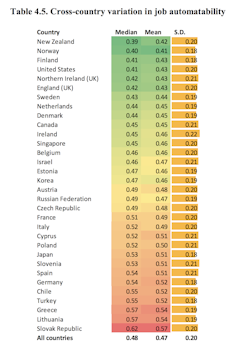

the median worker has 39% chance of their job being automated.

OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Paper No. 202

Other estimates are less dire. A report from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development says only 14% of jobs across its member nations are “highly automatable”, though another 32% are likely to change significantly.

Despite this uncertainty about the exact number of human jobs that will disappear, it is certain the impacts of automation driven by artificial intelligence (AI) are potentially profound.

If the new jobs that emerge as a result are fewer and less rewarding than those lost, we face a period of social dislocation.

Yet there is little evidence of any strategic planning and forward thinking by Australia’s federal and state governments to minimise the potential downside. The recent federal budget, for example, was silent on this issue.

It is analogous to the lack of a strategic plan on climate change.

Read more:

Your questions answered on artificial intelligence

Our concern about the policy vacuum is based on an extensive search on government websites, the media and budget speeches, which disturbingly yielded very little.

We think AI should be an election issue, because there is virtually no job that won’t be affected by AI-driven automation. Being ready for this technological and social revolution should be at the heart of any government’s economic and educational reform agenda.

Workers that never rest

The activities at which AI is expected to outperform humans by 2030 include translating languages, writing high-school essays and driving trucks. By mid-century it is expected AI could be capable of writing a bestselling books or performing surgery.

Researchers believe there is a 50% chance AI will outperform humans in all tasks in 45 years and that almost all current human jobs can be automated in 120 years.

www.shutterstock.com

The World Economic Forum may argue that AI and automation “is about empowering people, not the rise of the machines” but there are good reasons to think some people will lose out.

Read more:

Careful how you treat today’s AI: it might take revenge in the future

Machines have many attractions to employers. They do not need rest, holidays or take sick leave. They will never complain about overtime or join a union.

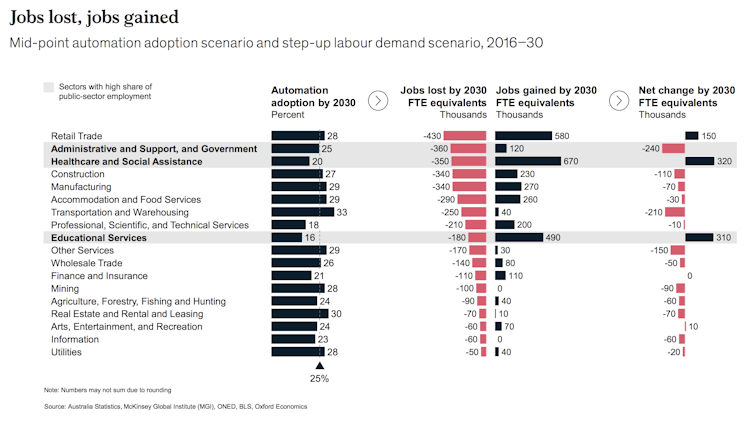

A report published last month by management consultancy McKinsey Australia suggests, if proactive measures are not taken, the unemployment rate could increase by 2.5 percentage points, based on up to 46% of jobs being automated by 2030.

Australia Statistics, McKinsey Global Institute (MGI), ONED, BLS, Oxford Economics

Inequality will also increase, the report says. To what extent depends on “how much Australia steps up its efforts to retrain and redeploy its surplus service, administrative and manual workers”. Without large-scale retraining, Australia’s Gini coefficient (the standard measure of income inequality) could increase from 0.32 to 0.41.

Questions for policymakers

The stakes are high. Employment is so much more than just an income. A decent job provides purpose and dignity. It enables security, health and well-being. Joblessness hurts the individual, families and the wider community. If fewer people have work, and more people get paid less, the federal government will have to contend with falling income-tax revenue and rising welfare spending.

With intensifying global competition and rapid technological change, all governments need to be strategic. They need long-term policies to help business and workers gain the knowledge, skills and abilities needed to seize the opportunities and mitigate the threats.

Read more:

Artificial intelligence can now emulate human behaviors – soon it will be dangerously good

There are three key questions for policy makers:

-

To what extent will AI-driven automation increase unemployment and underemployment?

-

How can governments and employers take advantage of AI and create the jobs of the future?

-

How can government, employers and educators equip employees and graduates with the skills to have jobs alongside robots, instead of competing with them?

The growth in AI and machine learning need not pose a threat to jobs and our standard of living, but without a strategic and shared effort, we will repeat the mistakes of previous technological revolutions, which imposed a terrible price on some in the name of progress.

The authors of this article are working towards a book, The Fourth Industrial Revolution: Implications for Managers in the Asia Pacific, due to be published in September. It will include chapters from colleagues in Taiwan, China, India, Mauritius, Singapore, Indonesia, Thailand and Malaysia. For the Australian chapter we need more information from leaders and managers in industry about the impact of AI and the preparation and planning that is, or is not, occurring. We invite you to complete a short survey as part of this study. You can do so confidentially here.![]()

Alan Montague, Senior Lecturer/Program Director, masters program in human resources management, RMIT University; Alan Nankervis, Adjunct Professor of Management, RMIT University; John Burgess, Professor of Human Resource Management, RMIT University; Nuttawuth Muenjohn, Senior Lecturer, Business, RMIT University; Ros Cameron, Head of Discipline, Human Resources Management, Australian Institute of Business, and Timothy Bartram, Professor, Management, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.