By Preti Taneja, University of Cambridge

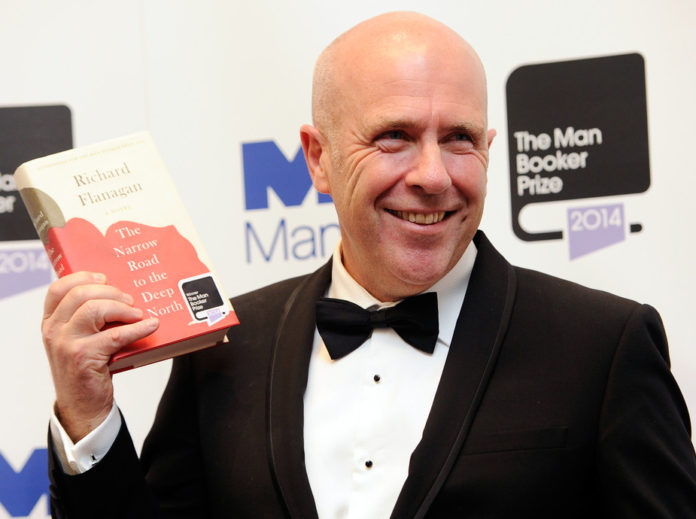

Richard Flanagan has won the 2014 Man Booker Prize with his novel The Narrow Road to the Deep North. Giving his acceptance speech he said:

In Australia the Man Booker is seen as something of a chicken raffle. I just did not expect to end up the chicken.

It’s a win that will probably find favour with Peter Carey, another Australian, and one of just three writers in the history of the Booker Prize to win it twice. The criteria for entering used to be books by “a citizen of the United Kingdom, the Commonwealth or the Republic of Ireland”; this year it was opened to all English language writers (including, of course, Americans) for the first time. Carey said recently that in changing the rules, a “particular cultural flavour” represented by Commonwealth literature was at risk of being lost.

Looked at another way, Carey’s statement suggests a certain kind of book usually wins, one that deals with the patchwork fabric of the Commonwealth; the complicated relationships between cultures and countries that are linked by a power dynamic located in the violence of colonisation.

That a UK-based prize – and one so powerful in the world’s literary marketplace – might be pulled by this undertow only reinforces the long shadow of cultural imperialism.

Flanagan’s novel, written with a devastating lyricism, lives up to this “type” entirely: it is the only shortlisted book by a Commonwealth writer, and tells the story of surgeon Dorrigo Evans, held in a Japanese POW camp while working on the construction of the Thailand-Burma “death” railway.

The vestiges of empire are everywhere: on the tortured bodies of the characters, in their voices, their memories, brought to life in the burning landscapes they move through.

In a piece for the Guardian on the morning before the announcement, Carey admitted that Flanagan’s novel was the only shortlisted book he had read:

Richard Flanagan clearly has to win. He’s our man. He’s a serious guy who can really, really write.

No comment on whether his being “our man” is because he’s Commonwealth, or Australian.

American others

So what of American writers, who, some say, are less concerned with the “others” beyond their own borders? Do they deal more in the strange minutiae of American life, are they more interested in examining the dystopia of the American dream than the world outside?

Though Karen Joy Fowler’s Booker-nominated We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves seems to fit the American bill, it actually adheres to the “flavour” of Commonwealth literary culture.

Yes, her novel goes down the rabbit-hole of American family life, via some familiar tropes of American campus novels and independent cinema’s loose groups of friends. But it does so to explore themes of world importance.

The novel is unafraid to investigate who the real “others” to humanity are; how they are treated; whether they can or should remain enslaved. It is a book of siblings and scientific ethics, of gender and patriarchy; it is absolutely haunting and amazingly fresh.

Long after its covers are closed, it demands that we think about who we are, and what role in the world we want to play.

The Booker type

Writers don’t have to tackle such themes explicitly to win the prize. Hilary Mantel, another two-time winner with the novels Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies, does not offer her readers contemporary history or scientific experiment. She achieves that “Commonwealth” sense of investigating identity through her precise choice of tense and perspective.

Her writing offers readers the chance to live in an eternally present moment from a history that formed our world. In making this choice she allows us to explore something about our own cultural DNA, to experience a time when the idea of dominance over the other, particularly a sense of British superiority over parts of the world, was being formed and consolidated.

The Booker committee emphasises that its criteria is wide, that it seeks to recognise “the best in English language fiction”. This year’s shortlisted books J by Howard Jacobson and How to be Both by Ali Smith are also on the list for the Goldsmith’s prize, given to “fiction that breaks the mould”.

The mould might be stylistic or thematic, or it might simply be the feeling that every reader gets of having read something similar before.

So what flavours should a prize-winning book contain? Flanagan’s novel answers this question through its steady depictions of violence, its careful attention to the idea that all sides are victims in terrible acts of war.

“How to be both” is absolutely the underlying theme here – and I’m with Ali Smith when she says: “Work that engages you sensorily, intellectually, to the heart. That will do it for me.”

![]()

Preti is the editor of Visual Verse, an online anthology of art and words, whose patrons include Bernadine Evaristo, Andrew Motion and Ali Smith. www.visualverse.org

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Read the original article.