Elizabeth C. Tippett, University of Oregon

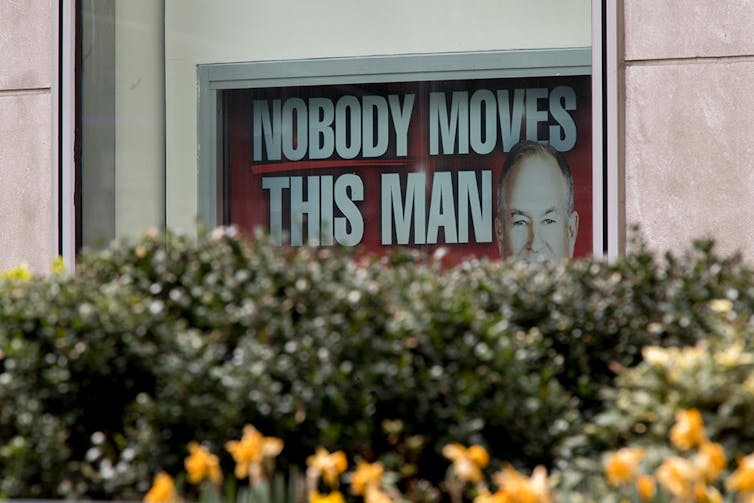

Harassment and abuse accusations against Harvey Weinstein and other prominent men, like Bill O’Reilly, have revealed a trail of settlement agreements in their wake, many of which contained language that prevented victims from speaking publicly.

These agreements have not been made public, although reporters have in some cases described their terms. Rose McGowan – who settled a claim against Weinstein in the 1990s without agreeing to confidentiality – recently refused an additional offer of US$1 million in exchange for secrecy.

States such as Pennsylvania, New Jersey and New York are working on legislation that would ban nondisclosure provisions in harassment settlements.

While nondisclosure agreements are currently getting a bad rap, they can serve a legitimate business purpose. It’s a mistake to think of them as a monolith; they come in a variety of forms and serve different functions. Understanding them can help reveal when they’re used appropriately – and when their real purpose is to conceal and perpetuate misconduct.

nito/Shutterstock.com

Settlements vs. standard confidentiality

When I worked as an employment lawyer, we dealt primarily with two different kinds of contracts containing nondisclosure provisions: standard confidentiality agreements that most employees sign at the start of their employment and settlement agreements used to resolve a lawsuit or a threat of one.

Confidentiality agreements are very common. They serve primarily to protect a company’s business information. They might prohibit disclosing research and development, trade secrets or other nonpublic information about the company’s business.

Depending on how it is worded, a standard confidentiality agreement might not even cover an employee’s disclosure about harassment she experienced. And even if it did, other legal principles likely protect an employee’s right to speak out.

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act protects an employee’s right to “oppose” harassment protects employees for opposing harassment and other forms of discrimination in the workplace, and there is some case law supporting the idea that public opposition to harassment such as writing letters or picketing are protected.

In addition, the National Labor Relations Act protects a worker’s right to engage in “concerted activity” – “acting together to improve wages or working conditions” – which arguably includes discussions on social media about a workplace rife with harassment.

In other words, an employee who suffers from harassment has many options for bringing attention to the problem. She is largely free to discuss it with co-workers, file a lawsuit or even discuss it publicly.

That’s where settlement agreements come in.

AP Photo/Mary Altaffer

Settlement agreements are different

A harassment victim would typically enter into a settlement agreement after a lawyer threatens to bring a lawsuit or actually files a lawsuit on the victim’s behalf. Through the agreement, the victim waives the right to pursue the lawsuit, usually in exchange for money. For example, former Fox News host O’Reilly reportedly settled a harassment claim for $32 million.

In settlement agreements, provisions intended to keep the terms secret or to prevent the victim from saying anything publicly about the harasser may be an important part of the deal.

Their purpose, however, is not always nefarious. Lawsuits are invasive, exhausting and expensive. Both victims and companies may have a legitimate interest in ending a protracted dispute. Secrecy-related provisions can serve to keep the peace once a settlement is finalized.

Common contract terms

Of course, these agreements are, by their nature, secret, which prevents those of us on the outside from knowing exactly how they were drafted.

However, the Securities and Exchange Commission’s website offers a glimpse into standard contract language, through posted agreements between companies and executives. (Such agreements with executives are commonplace, even without threatened litigation or suspected wrongdoing.)

Some contract provisions attempt to ensure secrecy by designating the contract terms as confidential.

But that covers only the contract, not the underlying allegations themselves. To prevent public statements, employers use what is known as a “nondisparagement” clause. These come in different forms. Narrower provisions prohibit only “defamation, libel or slander” – which would allow a victim to speak out, provided the statements are true.

A broader provision might prohibit disparaging any employees or prohibit “any action which could reasonably be expected to adversely affect the personal or professional reputation of [the company] or any of its … employees.”

In some cases, a victim’s obligations extend beyond mere silence and force them to speak in support of the harasser. New York Times reporters Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey described a provision in one of Weinstein’s agreements that required the victim to say “positive things” if the press ever inquired about Weinstein. Lauren O’Connor, an employee of Weinstein’s company, was apparently required to write a letter stating that she had a “good experience” at the company as part of her settlement.

The bad ones settle early

As the Weinstein example demonstrates, settlement agreements can be used to obscure wrongdoing and enable continued misconduct.

Michael Germana/STAR MAX/IPx

This can be especially true of lawsuits settled before a case is even filed, which can skew toward the more serious ones – and involve the most serious abusers. As law professor Jennifer Shinall observed, “[E]mployers have a financial incentive to settle the most egregious discrimination claims before a lawsuit is filed” to avoid “high damages at trial and … negative publicity.”

Or, in the words of labor scholars Zev Eigen and David Sherwyn, “employers settle cases with bad facts at early stages,” meaning the worst cases will never see the light of day.

Particularly when a company decides to keep a documented harasser on the payroll, these provisions can provide cover for continued harassment. Later victims may never learn of the pattern of misconduct, or only after they have initiated their own lawsuit.

Nondisparagement provisions: The real problem

Thus far, most of the public debate around these contracts relate to the secrecy of settlements. But it is the broad nondisparagement clauses, and those requiring affirmative statements, that perform most of the work in concealing misconduct.

Proposed legislation should take this into account. The proposed New York law does so by invalidating agreements with the “purpose or effect of concealing the details relating to a claim of … harassment,” which would include a broad nondisparagement provision.

Legislators should also consider an exception for the legitimate use of such clauses, such as in settlement of previously filed lawsuits. Narrow nondisparagement clauses – which prohibit only defamation, slander or libel – are also defensible because they protect against false statements.

Likewise, courts should approach these provisions in a balanced way, as they do with noncompete agreements, and consider whether they are unreasonable, overly broad or supported by a legitimate business purpose.

![]() Ultimately, employers would do well to reconsider why they demand broad nondisparagement provisions in the first place. Silencing the victim is a short-term fix. Their long-term interests may be better served by dealing with the harasser.

Ultimately, employers would do well to reconsider why they demand broad nondisparagement provisions in the first place. Silencing the victim is a short-term fix. Their long-term interests may be better served by dealing with the harasser.

Elizabeth C. Tippett, Associate Professor, School of Law, University of Oregon

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.