George Paxinos, Neuroscience Research Australia

In William Shakespeare’s comedy Merchant of Venice, the play’s heroine Portia sings:

Tell me where is fancy bred,

Or in the heart or in the head.

If you look at Valentine’s Day cards, it’s clear fancy is bred in the heart and not in the head; all the cards have red hearts on them. But they’re all wrong. Love does, in fact, live in the brain.

The irrelevance of the heart to love has been amply demonstrated by cardiac transplant surgeons. Heart transplant recipients do not fall in love with the lovers of the dead donors, Hollywood notwithstanding. Surely this proves that wherever else love may reside, in the heart it does not.

Further support for love’s actual home comes from neuroscience. This shows that love is a complex function, which includes appraisal, goal-directed motivation, reward, self-representation and body image – none of which can be found in the heart.

On the right track

Eden, Janine and Jim/Flickr, CC BY

Historically, the erroneous attribution of love to the heart can be traced to the ancient Egyptians of the third millennium BC. They considered the heart to be the seat of thought, memory, will and emotion. Hearts, stomachs and intestines were considered important for afterlife, but not the brain. Before burial, the ancient Egyptians heedlessly discarded the brain, so for millennia pharaohs arrived brainless for their afterlife.

The problem with the brain is that, unlike the heart, it doesn’t flutter when lovers kiss.

The scientist credited with the discovery of the relationship between the mind and the brain was Alcmaeon (circa 520-450 BC; possibly a student of Pythagoras) who lived in the Greek-speaking colony of Kroton (Crotone of today’s southern Italy). It’s thought Alcmaeon was led to his astonishing conclusion by observing that all senses are connected to the brain through channel-like structures. Today, we call them nerves.

Alcmaeon’s concept is thought to have passed on to the island of Kos, where Hippocrates (460-370 BC), the most significant physician of antiquity, worked. Hippocrates expressed an amazingly modern view:

Men ought to know that from the brain, and from the brain only, arise our pleasures, joys, laughter and jests, as well as our sorrows, pain, griefs and tears. Through it, in particular, we think, see, hear and distinguish the ugly from the beautiful, the bad from the good, the pleasant from the unpleasant…

Hippocrates’ view could be taught in any neuroscience department today.

A backwards step

Then things went downhill for the brain for a long while. Plato (429-347 BC) retained the primacy of the brain and attributed to it the seat of the rational, immortal soul. But, in his tripartite division of the soul, he confused matters and attributed to the heart the emotional soul.

Image Editor/Flickr, CC BY

The worst blow to the brain came from Aristotle (384-322 BC), who was Plato’s student, the greatest classical biologist and first anatomist. Aristotle observed that humans have the largest brain for their body size, but strangely he attributed to the brain the pedestrian function of literally cooling the blood. He placed the seat of the soul in the heart.

Aristotle’s views were dismissed as absurd by Galen (130-201 AD), who was an admirer of Hippocrates and served as physician to the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius. Galen proposed the psychic pneuma (mind) resided in the ventricles of the brain and, via the nerves, was in receipt of sensory information and controlled the muscles.

The cardiocentric (heart-centred, Aristotle) and encephalocentric (brain-centred, Galen) theories of the psyche/mind/emotions battled one another until the dawn of modern science.

Technology and the truth

Modern science has not only rejected the heart as the seat of love, but is making progress in identifying specific structures in the brain involved in the erotic, cognitive, emotional and behavioural components of love.

The first major work on the subject was published in 2000. Researchers studied the brain activity of people who were deeply in love via functional MRI while the subjects viewed pictures of their partners (compared to viewing friends of similar age and sex).

Soffie Hicks/Flickr, CC BY

The caudate/putamen (brain area receiving dopamine and involved with reward), medial insula (a multi-sensory area involved in the allocation of attention and control of the heart rate) and the anterior cingulate (an area involved in autonomic regulation, emotion and obsessive-compulsive behaviour) were activated. The amygdala (an area involved in fear) was deactivated.

Researchers have since extended these observations by showing that sexual desire and love recruit some common brain structures that promote bodily sensations, reward expectation and social cognition.

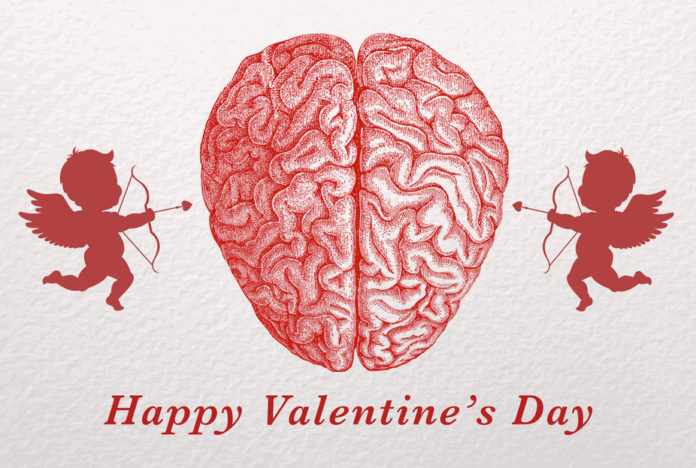

The notion that love doesn’t reside in the heart but in the brain is now as well established as the theory of anthropogenic global warming. Clearly, it’s time the fallacious cardiocentric theory of love is abandoned and on Valentine’s Day lovers exchange images of the organ really responsible for their emotion, whose shape is every bit as beautiful as that of the heart.

![]()

George Paxinos is Visiting/Conjoint Professor of Psychology and Medical Sciences, UNSW & NHMRC Australia Fellow at Neuroscience Research Australia.

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Read the original article.