David Scott Kastan, Yale University

When Americans hear some pundits projecting a “blue wave” in the 2018 midterm elections, they understand that this is a prediction of a big Democratic victory. Blue of course symbolizes the Democratic party, while red represents the GOP.

This might seem like a long-standing tradition, but it isn’t.

While writing my forthcoming book “On Color,” I was surprised to discover that this is a recent convention, not some practice with roots dating back to the birth of the two-party system.

Of course, there has always been color-coding in individual political campaigns. But for years, both major parties used the full panoply of American red, white and blue for their own self-identification.

With the spread of color television in the late 1960s, color-coded electoral maps were incorporated into election coverage, but neither red nor blue had been assigned a permanent side.

In Cold War America, networks couldn’t consistently identify one party as “red” – the color of communists and, in particular, the Soviet Union – without being accused of bias. (The color’s connotation was objectionable enough that Cincinnati’s professional baseball team officially changed its nickname from the Reds to the Redlegs between 1953 and 1959.)

So depending on the election or the network, red and blue were variously assigned to Democrats and Republicans. On election night in 1980, when it became clear that Ronald Reagan was going to defeat Jimmy Carter, a television anchor pointed to the color-coded studio map showing the emerging Republican victory and said it was starting to look like “a suburban swimming pool.”

As more states went for Reagan, his campaign workers gleefully began to refer to the increasingly blue map as “Lake Reagan.” Later in the evening, with all the states decided, the electoral map registering the magnitude of Reagan’s triumph had become, in the words of another TV commentator, an “ocean of blue.”

But after the 2000 presidential election, no Republican victory of whatever size would ever again be described using the color blue. That year, the networks had chosen red to represent states won by the Republicans and blue to represent states won by the Democrats. However, by the end of Election Night, neither George W. Bush nor Al Gore had a definitive electoral majority to turn the country red or blue.

All eyes were on Florida, where the result was too close to call.

For the next 36 days, the country anxiously followed the television coverage of recounts and court challenges. Only on Dec. 12, when the U.S. Supreme Court suspended the recount, did Florida officially become a “red state” – and Bush was elected the 43rd president of the United States.

Night after night of television coverage had fixed our political colors in the national imagination: red for Republicans and blue for Democrats. What was once discretionary and variable became a permanent feature of the country’s political imagery to signal the country’s ideological divide.

This unintended color-coding of American politics reversed the political associations of red and blue that exist almost everywhere else in the world.

In the United Kingdom, for example, the Conservative party color is blue, while the unofficial anthem of the Labour Party begins “The people’s flag is deepest red.”

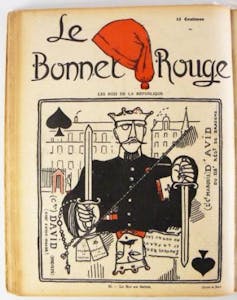

In various nations, red faces off against blue, replaying social and political divides that first assumed their ideological outlines and their primary colors in the French Revolution.

Wikimedia Commons

The bonnet rouge – the soft red cap worn by the French revolutionaries – symbolized their fervor and their solidarity. It was also a defiant appropriation of the red color worn by the government’s supporters. But it would come to be solely the color of the French left, and after the revolution at the end of the 18th century, red remained their color. When the radicals briefly controlled Paris in 1848 and again in 1871, they raised their red flag over the Hôtel de Ville.

The assertive red flag would become still more visible in the 20th century as the triumphal emblem of post-revolutionary Russia and of Communist China, which, along with the large Red armies and the Little Red Book, fueled the Red Scare in the United States.

![]() Now, in America, red has become the color of conservatism. An accident of media history, the current colors are evidence of the randomness and instability of political color codes – though it’s unlikely Donald Trump will be selling blue “Make America Great Again” baseball caps any time soon.

Now, in America, red has become the color of conservatism. An accident of media history, the current colors are evidence of the randomness and instability of political color codes – though it’s unlikely Donald Trump will be selling blue “Make America Great Again” baseball caps any time soon.

David Scott Kastan, George M. Bodman Professor of English, Yale University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.