Ruben J. Garcia, University of Nevada, Las Vegas

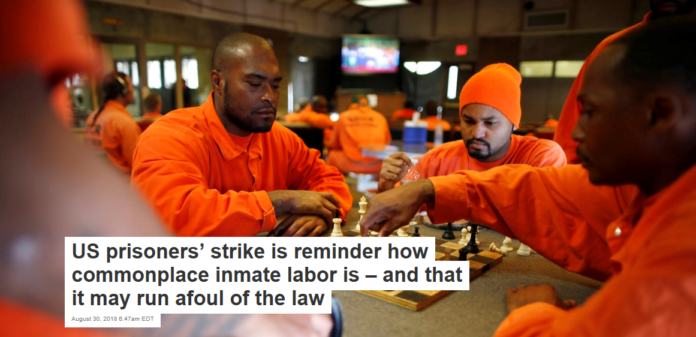

Prisoners in 17 U.S. states went on strike on Aug. 21 by refusing to eat or work to call attention to a number of troubling issues, including dilapidated facilities, harsh sentences and other aspects of mass incarceration in America.

As we approach Labor Day, the strike places a spotlight on the questionable practice of putting prisoners to work for very low or no wages. Examples of what incarcerated people do or have done include answering customer service phone calls, fighting wildfires, packaging Starbucks coffee and producing consumer goods such as lingerie.

But this practice may run afoul of several U.S. legal commitments – including the 13th Amendment ending slavery – and even violates voluntary codes of conduct of some of the companies involved.

I belong to a group of scholars of U.S. constitutional law, labor law and history from several universities, who see the 13th Amendment as about more than 19th-century slavery, even if that was its primary genesis.

Rather, we consider it a continuing obligation on governments and private companies to root out all forms of economic exploitation, even when it is done within prison walls.

Prisoners at work around the world

Prison labor is widely used in many countries throughout the world on every continent, involving an estimated 36 million people.

Proponents of forcing inmates to work justify it as a way for prisoners to repay their debt to society and to provide skills that will be useful at the end of prison sentences. They say it also partially offsets the high costs of mass incarceration, recently estimated at US$182 billion a year nationwide.

The U.S. government has often admonished other countries such as Burma and China for using forced labor to build pipelines or make goods or in times of national emergency. Yet the truth is, it’s just as prevalent in the U.S. as elsewhere, with the Department of the Navy and Minnesota among the governmental entities sued for minimum wage violations in prisons.

In fact, a 2004 economic analysis of labor in both state and federal prison estimated that in the previous year inmates produced more than $2 billion worth of commodities, both goods and services.

And many private businesses have used prison labor, such as Victoria’s Secret, Starbucks and Microsoft.

Even immigrants awaiting deportation proceedings were forced to do janitorial and clerical work for $1 a day at the private detention facilities where they were held, according to recent litigation. Inmates have claimed in lawsuits that they earned as little as 12 cents an hour – or nothing as all, as is legal in some states.

The 13th Amendment

Unlike other countries, however, forced prison labor in the U.S. must be reconciled with the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which is most famous for forbidding the practice of slavery.

The 13th Amendment, ratified in 1865, states in full:

“Section 1. Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as punishment for a crime for which the person has been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States or any place subject to its jurisdiction. Section 2. Congress shall have power to enforce this Article by appropriate legislation.”

The first section of the amendment makes clear that people convicted of a crime can be forced to work as punishment but says nothing about whether they have to be compensated.

And according to the second, Congress clearly has the power to regulate inmate labor in federal prisons but has not done so. Lawmakers have, however, passed other laws that may already apply to prisoners with jobs, such as the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, which guarantees a minimum wage and overtime to all of those employed in the U.S.

While some U.S. courts have suggested that prisoners working for private companies be paid like other employees, there’s been no definitive decision on this issue.

chrisdorney/shutterstock.com

Expanding its meaning

The group to which I belong, known as the Thirteenth Amendment Project, aims to find ways to use the Amendment to reduce economic injustice in the U.S. and tackle problems such as minimum labor standards and mass incarceration.

In our view, the meaning of “involuntary servitude” in the amendment has a wider reach than simply the abusive arrangements that were in place in 1865. We believe it should also include modern conditions facing immigrant workers, detainees and workers bound to abusive contractual work arrangements – the kind that the Supreme Court struck down in the 20th century.

In addition, the Reconstruction-era drafters of the Amendment sought to prevent the newly freed slaves from becoming unfair competition in the labor force. So they instituted labor protections into the infrastructure of the Freedman’s Bureau, which Congress set up in 1865 to help former black slaves as well as poor whites in the South in the aftermath of the Civil War.

The Freedmen’s Bureau offers evidence of the role that Congress envisioned under the amendment to protect freed slaves and others against exploitation and unfair competition – which, in my view, are both at issue today in the context of unpaid prison labor.

International obligations

Beyond domestic law, there’s the issue of the United States’ obligations under international human rights conventions.

The U.S. is a member of the International Labor Organization, which as a core principle requires the elimination of forced and compulsory labor within its borders.

The organization also established a convention on forced labor in 1930. It makes clear that while governments in some circumstances can use forced labor, the work cannot be “hired or placed at the disposal of private individuals, companies or associations.”

The U.S. is one of only nine countries that have not ratified this convention, putting it in the company of countries like Afghanistan, China and Brunei. The reason often given is that the 13th Amendment already covers forced labor. But as I’ve shown, the question of compensation is an open one.

Flickr/Tom MacWright

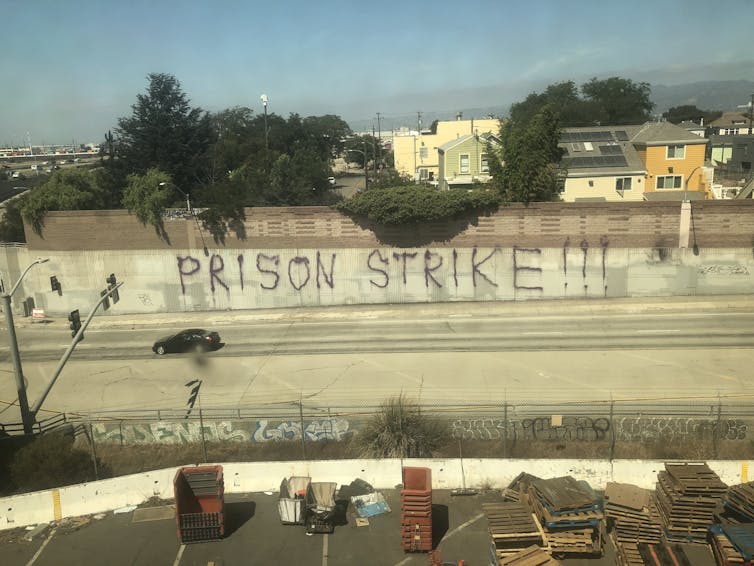

The strike’s legacy

The prisoners currently protesting their poor treatment and conditions probably may not expect that it will lead to the end of prison labor.

And whether or not the 13th Amendment or international conventions ultimately limit or end the practice – or at least require fair compensation – will likely depend on the United States Supreme Court.

The real success of the prison strike, set to last through Sept. 9, may be whether consumers become more aware that some of the coffee, clothing and even school supplies they buy may have passed through the hands of inmates, who were paid little to nothing for the work.![]()

Ruben J. Garcia, Professor of Law, Co-Director of UNLV Workplace Law Program, University of Nevada, Las Vegas

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.