By David S. Wall, Durham University

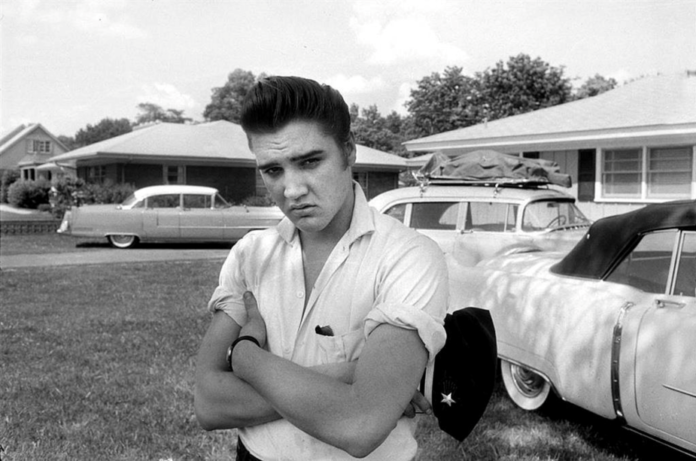

When asked in 1977 what he would do now that Elvis was dead, his manager Colonel Parker allegedly replied: “Why, I’ll just go right on managing him!”. In Parker’s mind, neither Elvis’ name, image, likeness and sound nor his economic value died with him.

On January 8 2015, Elvis would have been 80 years old. And nearly 40 years after his death, he continues to appear among Forbes Magazine’s top-earning dead celebrities, even if he has been toppled from the number 1 spot by by Michael Jackson.

But there is another side to the Elvis legacy. On top of his cultural contributions and the cash he continues to generate for those associated with him, he has made a rather significant post-mortem contribution to legal history. Those who have successively managed his image and likeness – and of course Colonel Parker was the first – have been at the vanguard of the celebrity character merchandising industry.

They have contributed to the development of celebrity rights law, especially the US right of publicity as an intellectual property right that can be passed on to heirs, rather than simply a personal right which dies with the owner. That means that a celebrity’s children can not only inherit the rights to exploit his or her image and likeness, but also sell them on to others.

Courthouse rock

Most significant has been their management of the paradox of circulation and control. They balanced the need to protect the holder’s exclusive rights over the property whilst also allowing some circulation of the Elvis signs and symbols to enable entirely new and younger audiences to engage with Elvis and keep him alive in the public consciousness.

Parker’s fighting words of 1977 were fairly short-lived. He soon found it increasingly difficult to apply the exclusive control that he once exercised over the Elvis brand, particularly after his own competence as guardian of the Elvis legacy was called into question.

When Parker lost his grip, Elvis Presley Enterprises was formed to manage the estate. It sought to first consolidate all Elvis assets, then expand the business they generated. Facing bankruptcy, one of its earliest moves was to open Graceland to the public on a commercial basis in the early 1980s.

The next strategy was to gain legal control over the most valuable asset – the Elvis Presley name, image and likeness. This was achieved over the next decade or so through five major US legal actions. Factors v Pro-Arts defined control of his likeness, while Memphis Development fought Factors between 1977 and 1980 for control of his name. The next two cases confirmed the “descendibiity” of the rights to his heirs.

The final lawsuit in 1991 – which saw the small UK firm Elvisly Yours barred from trading in goods bearing the name or likeness of Elvis Presley – effectively put the genie back in the bottle. Elvis Presley Enterprises became regarded as the Darth Vader of character merchandising. It had effectively put a stop to anyone else profiting from Elvis.

The world wide wonder of you

The problem for Elvis Presley Enterprises and later for their successors was that in the early days of the internet, the Elvis likeness became one of the images most exploited by websites. Its use was so widespread in the 1990s and early 2000s that there was concern that it would become generic –– exactly the worry that keeps all intellectual property lawyers awake at night.

Elvis began to be “consumed” in new and unexpected ways via the internet. Academic courses on Elvis study emerged, he became a spiritual icon, and a number of Elvis-based religions were founded.

Demand for Elvis continues to outstrip supply.

Kevin Dooley, CC BY

Offline, he has been cloned, in the sense that he was, and still is, widely impersonated and sampled on modern music tracks. He has even been digitally recreated in official tribute concerts with his original backing band.

Slightly less suspicious minds

While the public is still expected to pay for the privilege of consuming the King, there has been a change of approach when it comes to the legal side of his legacy more recently.

No home is complete…

There is less litigation than in the past and “cease-and-desist” letters are becoming infrequent. A licensing policy is now the favoured approach, ensuring that revenues are generated from these new forms of consumption. In my own household, for example, we now proudly own, amongst the merchandising, a licensed Elvis ironing board.

Elvis at 80 is a piece of intellectual real estate that can be traded on the market. In 2005, Elvis Presley Enterprises sold 85% of the rights to Elvis to CKX Inc (now Core Media Group) and in 2013 these rights were sold on to the Authentic Brands Group.

His popularity shows no sign of waning – Graceland is the second most visited private residence in the US next to the White House. The question is, though, is whether or not his enduring popularity a result of his commodification or does it come in spite of it? Given that Graceland was almost bankrupt 35 years ago and is now a thriving business built around Elvis, the balancing act between circulation and control of the images seems to have worked.

But I do wonder what would happen if Elvis were still alive on his 80th birthday, because there are still those who think he still lives. Could he knock on the door of Graceland to say that he wants to be Elvis again or would he have to pay a licence fee to do it?

![]()

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Read the original article.