Katherine Richardson Bruna, Iowa State University

If humans and mosquitoes had a battle at the end of the world, who would win? That’s the question I pose to 30 young kids each summer during a two-week camp called “Mosquitoes & Me” in Des Moines, Iowa. https://www.youtube.com/embed/0M3uxRbN3Mc?wmode=transparent&start=0 The ‘Mosquito and Me’ summer camp in Des Moines, Iowa.

I am an educational anthropologist who studies the cultural dynamics of science education. Along with my colleagues Lyric Bartholomay and Sara Erickson, who help run the camp, we have the young camp participants explore the “end-of-world battle” question as they learn about mosquito biology, ecology and disease transmission. Based on what the kids learn from their hands-on activities, they design a mosquito comic book character that is either a hero or a villain.

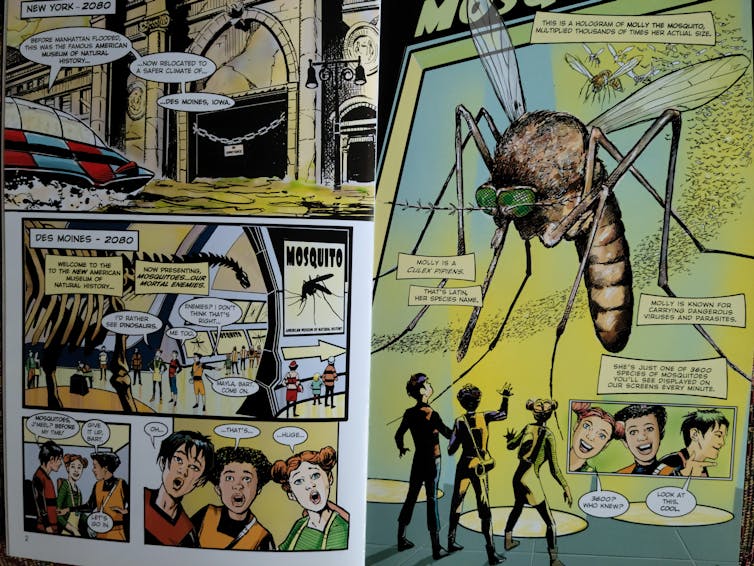

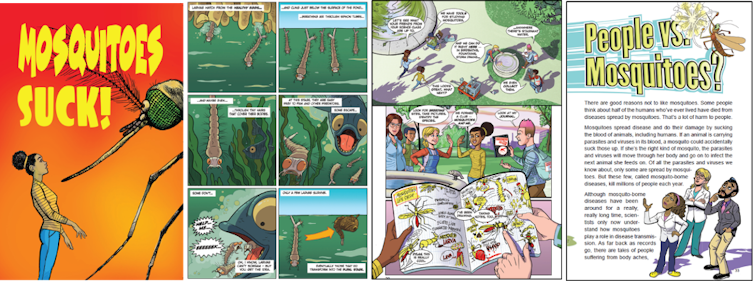

Since this approach was such a big hit, we worked with Marvel Comics artist Bob Hall to convert “Mosquitoes & Me” into an actual comic book. Some of our young scientists drew images of themselves and made up catchy public health slogans for a page about mosquito control. The idea is to reach kids who can’t attend “Mosquitoes & Me” camp by offering to teach them cool facts about mosquitoes.

Feeding habits

Before we make the comic book, some serious science has to take place. While at the camp, a group of mostly Black and Latino elementary and middle schoolers who are interested in science work in teams. They learn everything they need to know to decide whether humans or mosquitoes would win in an end-of-the-world battle.

They explore mosquito ecology by looking for larvae in local water spots. They examine the important role that mosquitoes play in the ecosystem. They tackle the logistics of disease transmission by thinking through whether mosquitoes actually “bite” or “suck.” And they learn about mosquito biology by feeding larvae foods made from their own kitchens.

The activities engage them in authentic science practices like data tabling, microscope use and dissection. At the end of camp, they create public service announcements to teach mosquito control and disease prevention.

Taking a more involved approach

Research has found that students who experience hands-on learning outperform students who receive more traditional instruction. Most importantly, hands-on science gives them an experience with “object intimacy.” This is a feeling of developing a relationship with the thing they’re studying.

Broadening participation by helping young people “fall for science” is imperative in increasing diversity in entomology – a field in which disparities persist, particularly for African Americans.

Less than 2% of the membership of the Entomological Society of America identifies as African American.

Students from underrepresented backgrounds who understand how science can serve their communities show stronger motivation to persist in science studies. Our overarching goal is that the hands-on approach of “Mosquitoes & Me” helps youths, especially those who aren’t engaged by a traditional school science curriculum, see the relevance of science – and especially entomology – to themselves and their community.

Solving real-world problems

In 2019 roughly 409,000 people died from malaria worldwide. Even though the “skeeter scientists” of “Mosquitoes & Me” summer camps live far away from the countries where malaria remains a dire threat, scientists anticipate that climate change will exacerbate conditions in the U.S. – especially in urban areas – for other mosquito-borne diseases. These include dengue, West Nile virus, chikungunya Zika and yellow fever.

Community members play a significant role in reducing the prevalence of mosquitoes in urban areas. Since entomology is a predominantly white field, residents of urban neighborhoods may be distrustful of entomologists who, to do their work, need to place traps in and around their homes or neighborhoods and do “surveillance” on trash, flower pots, toys, tires and other items that collect water and cause mosquito habitats.

The young skeeter scientists of “Mosquitoes & Me” can help their families make sure that everyday items don’t end up holding standing water and become attractive habitats for mosquito moms to lay their eggs.

“Mosquitoes Suck!” begins with humans winning the end-of-world battle. But promoting environmental education that avoids such a standoff is the prevailing theme. If humans drive mosquitoes to extinction, we will all lose. They are an essential part of life’s intricate interdependence.

Through “Mosquitoes & Me,” we are helping a future generation of diverse potential scientists and their educators fall for mosquitoes, and for science.

[Over 106,000 readers rely on The Conversation’s newsletter to understand the world. Sign up today.]

Katherine Richardson Bruna, Professor, Sociocultural Studies of Education, Iowa State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.