Thomas Begley, University at Albany, State University of New York and Marlene Belfort, University at Albany, State University of New York

Although there are striking differences between the cells that make up your eyes, kidneys, brain and toes, the DNA blueprint for these cells is essentially the same. Where do those differences come from?

Scientists are realizing the defining qualities that make up each cell actually lie in a cousin of DNA called RNA.

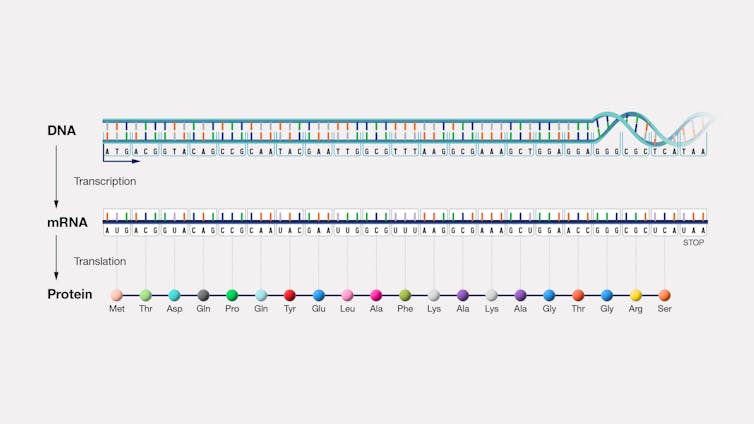

RNA was long considered DNA’s boring biochemical relative. Researchers thought it merely takes the genetic information stored in DNA and delivers it to other parts of the cell, where it is then used to make the proteins that carry out the cell’s functions.

But only roughly 2% of DNA codes for protein. The rest – sequences of the DNA that don’t code for proteins – is what scientists consider the dark matter of the genome, and there is much interest in figuring out what it does. Therein lies much of the mystery and magic of RNA.

In this dark matter, noncoding DNA is transcribed into noncoding RNA. These include RNAs small and long that are never translated into protein, and have the potential to regulate the genome and generate the diversity of cells by turning on or off various genes. When these multifaceted RNAs go awry, they can lead to a broad array of diseases in people.

RNA scientists like those on our team are now working to sequence every human RNA as part of the Human RNome Project – the RNA equivalent of the Human Genome Project – to aid in human health and improve treatments for disease.

RNA modifications orchestrate cell fate

DNA details how genes can become proteins, while RNA signals when and where these proteins are made. In other words, DNA is information storage while RNA is information access and regulation.

RNA has many varieties that differ by size and structure, with smaller forms that are involved in cell regulation and development. Much of the RNA that is transcribed from DNA is processed and modified after it is made.

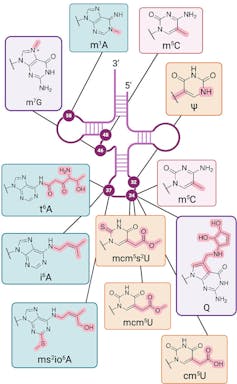

RNA modifications are chemical structures added on to RNA that regulate information transfer. These RNA modifications are distinct from DNA modifications that are known as epigenetic marks. Whereas DNA modifications can be inherited, RNA modifications arise in response to the current state of the cell. RNA modifications are more dynamic and have more dramatic effects on the structure and function of the cell, including how proteins are made under different cellular conditions.

Under normal conditions, for example, some RNA modification patterns trigger the disposal of RNAs that code for or help decode stress-response proteins. When the cell enters a state of stress, this modification pattern is reprogrammed so these proteins can accumulate and help the cell recover.

Additionally, the chemical diversity of RNA modifications is greater than that of DNA modifications. In addition to variations in the basic building blocks that make up RNA, there are over 50 chemical varieties known as the human epitranscriptome in a cell. In comparison, epigenetic marks number in the handful.

Collaborations between our lab and others have identified increased levels of modification to specific types of RNA, called transfer RNA, that deliver the building blocks of proteins to the parts of the cell assembling them. These tRNA modifications can be a key driver of cancer and resistance to chemotherapy, and they are also linked to developmental and neurological diseases.

RNome to understand health and disease

Compared to DNA, RNA is more unstable and structurally diverse, and there are fewer tools available to study and sequence it. While many resources and efforts were made to sequence DNA through the Human Genome Project, sequencing RNA and its many modifications remains a challenging task.

But with advances in technology, researchers are now able to study RNA modifications and recognize their potential to treat or prevent disease. The past 20 years of research devoted to RNA modifications has led to what scientists have called an RNA Renaissance, catapulting RNA to become one of the most attractive macromolecules to study and use as vaccines and medicines.

Understanding and harnessing the power of the dark matter of RNA requires a project on the scale of the Human Genome Project. Labs around the world are using new technologies and approaches to sequence all RNAs, called the RNome. Cataloging and defining RNA and its modifications in healthy and diseased cells will require even further advances in sequencing technology so that it can detect more than one modification at a time.

We believe maps of the RNome will spur new technologies, new discoveries and provide a path to new treatments, improving human health on a grand scale.

Thomas Begley, Professor of Biological Sciences, Associate Director of The RNA Institute, University at Albany, State University of New York and Marlene Belfort, Professor of Biological Sciences, Senior Advisor of The RNA Institute, University at Albany, State University of New York

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.