When it comes to the case of Brown v. Board of Education, the 1954 Supreme Court decision that outlawed school segregation, the focus is often on Topeka, Kansas, the home of the Brown family and the school board that it sued. But the story of the case actually had several starts, years before the case was decided and more than a thousand miles away.

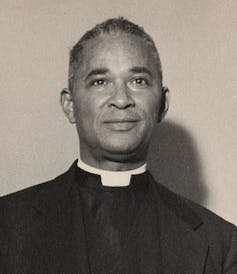

In 1947, Black families in Clarendon County, South Carolina, asked the county to provide school buses for Black children, just as it did for white children. The county refused, so with the help of the NAACP, the nation’s oldest civil rights organization, 20 Black parents prepared to sue, led by Joseph A. De Laine, a local reverend and public school principal.

Even before the suit was filed, one of the parents, Harry Briggs, was fired from his job at a local service station and had to leave the state to find a new one to support his family. And De Laine himself was fired from his principal’s position

Various legal and procedural hurdles followed, during which the NAACP decided the best strategy for making a case would be based not on busing but overall educational equity. In 1951, the organization filed a federal lawsuit demanding that Black students should get the same educational resources and facilities as white children. The suit pointed to Scott’s Branch High School, an all-Black school in Summerton, one of the towns in Clarendon County. Even the school district’s lawyers admitted that the town’s all-white Summerton High School had substantially better facilities, equipment and educational quality.

During a pretrial hearing, federal Judge Julius Waties Waring persuaded Thurgood Marshall, the attorney handling the case on behalf of the NAACP, to argue against school segregation itself, saying, “Bring me a frontal attack on segregation. I don’t want another separate but equal case.” A month later, Marshall brought a new case, Briggs v. Elliott, named for one of the 20 petitioners, arguing that school segregation in South Carolina was unconstitutional. This was the first lawsuit in the country to challenge school segregation as a violation of the U.S. Constitution.

The Brown v. Board case eventually grew out of that South Carolina case. As someone who has been in close contact with descendants of several family members who had direct involvement in the Briggs case, I believe the outcome of their struggle was a turning point in the fight for equality.

Fighting the constitution

The plaintiffs of the Briggs v. Elliot case sought to challenge the South Carolina state constitution, which established its separate school system. According to the 1895 state constitution:

“Separate schools shall be provided for children of the white and colored races and no child of either race shall ever be permitted to attend a school provided for children of the other race.”

The lawyers defending South Carolina’s school segregation system acknowledged the state’s Black and white schools were not equal. But they pointed out efforts by the new governor, James F. Byrnes, a former U.S. Supreme Court justice and devout segregationist, to raise the state sales tax to fund new buildings and improved programs. That should be enough, they argued, to solve the problem at the heart of the lawsuit.

Since it was a challenge to the state constitution, the Briggs case had to be heard by three judges in the federal District Court in Charleston, one of whom was Waring. The ruling was a split decision, with Judges John J. Parker and George B. Timmerman ruling that South Carolina’s segregation requirement did not violate the 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. But Waring disagreed, writing “segregation is per se inequality.”

When the case was appealed to the Supreme Court, it was combined with four other very similar cases, including the Brown v. Board case from Kansas.

Retaliations

Before the Supreme Court ruling, De Laine moved about 50 miles away, seeking to escape the harassment he was experiencing from segregationists in Summerton. After he moved, they burned down his Summerton home.

In his new town, De Laine also faced opposition, including from S.E. Rogers, the attorney for the defendants in the Briggs case, who organized a group of local segregationists to rally against integration.

De Laine’s new home, next to the church to which he had been assigned, was vandalized multiple times, and the church was burned down on the night of Oct. 5, 1955. Five days later, De Laine fled South Carolina after learning he would face attempted murder charges for shooting back at a car filled with threatening segregationists. He eventually made his way to New York.

The aftermath

It took years after the landmark Brown decision for its effects to really be felt in South Carolina. The first K-12 district in the state to desegregate was Charleston County School District, in September 1963.

Clarendon County school officials decided to close Summerton High School in 1966 to avoid integration. Instead, white parents sent their children to the newly built private Clarendon Hall school. Meanwhile, the Black students remained at Scott’s Branch High School.

Summerton High School stayed closed for over 20 years, only reopening in the late 1980s as an administrative office for the school district.

Although the outcome of the Brown decision arguably led to equal facilities, resources and bus transportation, it fell short of significantly integrating Black and white students in the district’s public schools. In 2022, Summerton public schools remained 95% Black, while most white students in Summerton attended the private Clarendon Hall school.

Roy Jones, Professor of Leadership, Counselor Education, Human and Organizational Development; Executive director, Call Me MISTER, Clemson University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.