Patricia Smith, University of Michigan

Republicans aim to tighten the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program’s work requirements as part of the farm bill Congress is debating.

These changes would cut spending on this nutritional benefit for the poor – commonly called SNAP or food stamps – by more than US$17 billion over the next decade and reduce the number of Americans getting these benefits by about 1.2 million.

As an economist who studies nutrition policy, I’m discouraged by continuing pushes to cut SNAP. By many measures, SNAP is fulfilling its mandate to meet an essential human need.

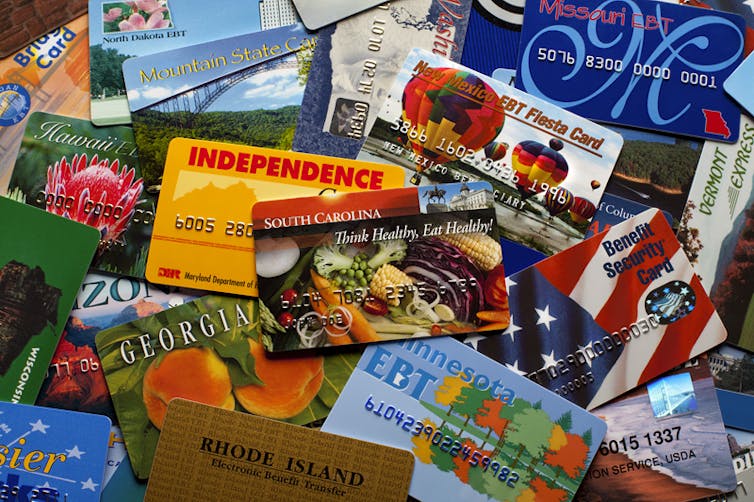

Jonathan Weiss/Shutterstock.com

Some fact-checking

Under new federal rules that President Donald Trump says he would sign, SNAP work requirements would change and be subjected to new layers of scrutiny. Just about all adults between the ages of 18 and 59 would have to work. The states, which administer this federally funded program, would lose their enforcement discretion, with the rules becoming stricter and less flexible.

To justify these changes, White House Budget Director Mick Mulvaney and other Republicans have long argued that the government wastes money on aiding “able-bodied” people who ought to provide for themselves.

But nearly two-thirds of SNAP participants are children, elderly or disabled and thus not expected to work. What’s more, 44 percent of Americans who rely on SNAP live in a household with at least some earnings. Furthermore, when able-bodied adults who aren’t caring for a dependent qualify for SNAP benefits, they lose them within three months if they aren’t working at least 20 hours a week. The farm bill would raise this federal minimum to 25 hours in 2026, and the states may set a minimum of up to 30 hours.

Research indicates that these benefits go where they are intended: to the poor. It’s true that some people get benefits who shouldn’t, and others who should get benefits don’t. But SNAP’s approximately 3 percent “error rate” is much lower than for Medicaid, Medicare, unemployment insurance and most other big government programs. Losses due to SNAP recipients selling their benefits amount to only about 1.5 percent of the program’s total benefits, according to the USDA.

That is why economists generally regard SNAP as an efficient and effective program.

USDA

Encouraging work

The Trump administration and GOP lawmakers say job requirements make the poor more self-sufficient.

But research indicates that SNAP benefits do little to discourage paid work. More than half of the non-disabled, working-age adults getting these benefits work. Even more – 80 percent – are employed the year before or afterwards.

Besides, SNAP benefits average just $1.40 per meal per person, offering a meager incentive to remain unemployed.

The economics

The program currently costs around $70 billion a year, around 2 percent of the federal budget. It helps millions of vulnerable Americans by reducing food insecurity and economic hardship and solves other problems indirectly.

For example, food insecurity increases the risk of many ailments. Children who get too little to eat are more likely to have anemia, asthma, cognitive problems and behavioral problems. Food-insecure working-age adults report more hypertension and sleeping problems. Seniors who don’t eat right are more likely to experience depression. Children of pregnant women who get food assistance are less likely to become obese or have hypertension or diabetes.

Low-income Americans who lose SNAP benefits would probably have more health problems, and the harm can be lasting. This bodes badly for low-income Americans’ ability to support themselves.

And since SNAP automatically responds to the business cycle, the program stimulates local and national economies during economic downturns. Each $5 the government spends on SNAP triggers $9 of economic activity and every $1 billion in benefits creates roughly 9,000 jobs, economists estimate.

The upshot is that lots of people could soon be spending less on food and thousands of Americans could lose their jobs – mostly in retail and farming. And more Americans will eventually suffer during the next economic downturn.

![]() This is an updated version of an article originally published on June 25, 2017.

This is an updated version of an article originally published on June 25, 2017.

Patricia Smith, Professor of Economics, University of Michigan

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.