By Reema Rattan, The Conversation

A second case of a baby who was ostensibly “cured” of HIV after early treatment has been discounted as a possible breakthrough in fighting the disease.

The case of an Italian baby who relapsed after appearing to clear the HIV virus is not comparable to the “Mississippi baby” who showed no sign of the virus for 27 months after treatment stopped, experts say.

“It is of absolutely no surprise that the [Italian] child rebounded because that is what happens in 99% of people who stop treatment,” said Professor Sharon Lewin, director of the Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity at The University of Melbourne.

“When the case of the Mississippi baby was recorded, she had been off treatment already for 18 months and had no rebound – and that was totally unique,” she added. “Of course, she went on to rebound after 27 months, but the fact that she went that long was what made her unique.”

Head of the HIV Service at the Sydney Children’s Hospital, Professor John Ziegler said the two babies’ circumstances were completely different.

“The two babies had quite different exposure histories,” Professor Ziegler said.

According to a case report published today in The Lancet, the so-called Milan baby was born to a HIV-positive mother whose status wasn’t known until she went into labour. Tests conducted within 12 hours of his birth showed a massive load of HIV in his blood and doctors started him on prophylaxis treatment.

“Prophylaxis is the standard approach for treating high-risk infants, who are born to HIV-positive mothers who haven’t received treatment,” Professor Lewin said. “The idea here is that you stop that infant from getting infected.”

While the HIV status of the Mississippi baby’s mother was also not known until she was in labour, the child was given the full suite of antiretroviral treatment 30 hours after her birth.

Doctors started the Milan baby on equivalent treatment when he was four days old, and the virus was no longer detectable in his blood after six months. Antiretroviral therapy was stopped when he was three years old and his viral load rebounded.

Doctors lost contact with the Mississippi baby and her mother when she was 18 months old. When they next met the child, she had been off antiretrovirals for five months and did not show signs of the virus. It wasn’t until the child was four years old that HIV was again detected in her blood.

The exact reasons for the different outcomes are not known, but there are several possibilities.

“The Mississippi baby didn’t get prophylaxis and then full treatment, she got full treatment from the word go,” Professor Lewin said. “We don’t know whether that made a difference or not but that was one key difference.”

According to the authors of today’s case report, another reason for the Milan baby’s early viral rebound could be the timing of the infection.

Professor Ziegler said the Milan baby’s high viral load at birth suggested he had been infected for many days, or weeks already.

“That means he was exposed to the virus when his immune system was very immature, so you’d expect a very high burden of infection,” he said.

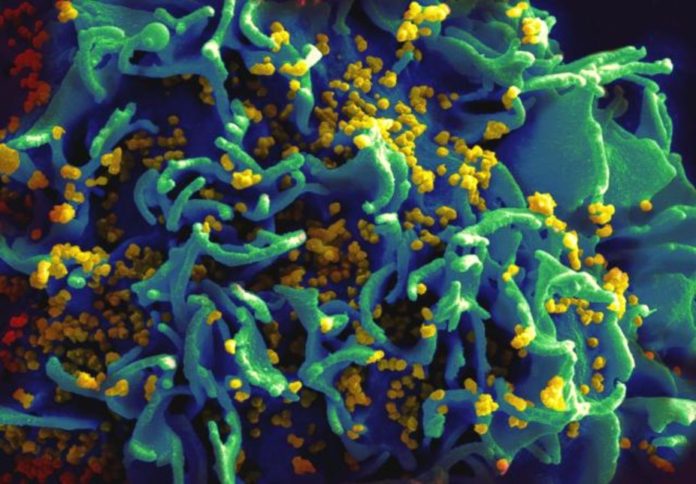

Professor Lewin said HIV, like some other viruses including the herpes virus, found places to hide in the body so it persisted even when blood tests fail to find traces.

We think long-lived immune cells, known as T cells, are probably the most important HIV reservoir, she said. They are known as memory cells because they “remember” pathogens they have encountered before, which is how we are protected from an infection after receiving a vaccine. Most babies’ T cells are not yet memory cells because they have not been educated to become memory cells.

“It is possible that treating a baby very early means that you can reduce the amount of virus that goes into hiding, because there just aren’t any memory cells around to infect,” she said.

![]()

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Read the original article.