Charles Helm, Nelson Mandela University

If you visit a particular stretch of South Africa’s Cape South coast, about 400km east of Cape Town, you are stepping back in time – in more ways than one. That’s because hundreds of fossil tracksites dot the area. These sites date back to between 400,000 and 35,000 years ago, during the Pleistocene Epoch. They occur in aeolianites (cemented dunes) and cemented foreshore deposits, the remains of dune and beach surfaces on which animals left their tracks.

Since 2007 our research team has identified more than 250 fossil tracksites on the Cape south coast, revealing unexpected findings that were not apparent in the traditional body fossil record. For example, giraffe, hatchling sea turtles and crocodiles once inhabited this coastline.

Read more:

First fossil trails of baby sea turtles found in South Africa

Our latest work has centred on avian tracksites, revealing evidence for the first time from this period of some of the bird species that once roamed the Cape south coast. In an article recently published in the journal Ostrich, we summarised our findings from 29 sites on that coast.

One avian track, probably made by a large gull or a small goose, was found in sediments that have been dated to about 400,000 years. That makes it the oldest avian track reported from southern Africa.

Six of the tracksites we identified showed evidence of large avian trackmakers. For example, tracks at one site that appear to have been made by a crane were larger than any extant crane species in Africa, and a trackway at another site closely resembled that of a flamingo – except that the tracks were larger than those of the extant Greater Flamingo.

At this site, which was remarkably well preserved, we also documented flamingo feeding traces for the first time in the global fossil record. The creation of these traces can be readily observed in flamingo behaviour today: the birds stir up their food supply by “rhythmic stomping” or “marking time” while moving slowly backwards, resulting in “tramline traces”.

Vera Larina/Shutterstock

These tracksites have the potential to complement the traditional body fossil record and offer more insights into what flora and fauna occurred in the region during the Pleistocene, mostly in the 130,000 to 80,000 year age range. They can also help us understand which of these species may have become extinct, perhaps driven by climatic shifts. This finding was unexpected, as there was no previous evidence of Pleistocene avian extinctions in Southern Africa.

Tracing the tracks

Avian tracks tend to be less common and less obvious than mammal and reptile tracks. This is partly because birds fly and perch, so many species left few tracks to be interpreted today. Our findings of bird tracks on what were beaches and dunes is extremely unusual – globally, most fossil bird tracks are found on the margins of lakes and lagoons.

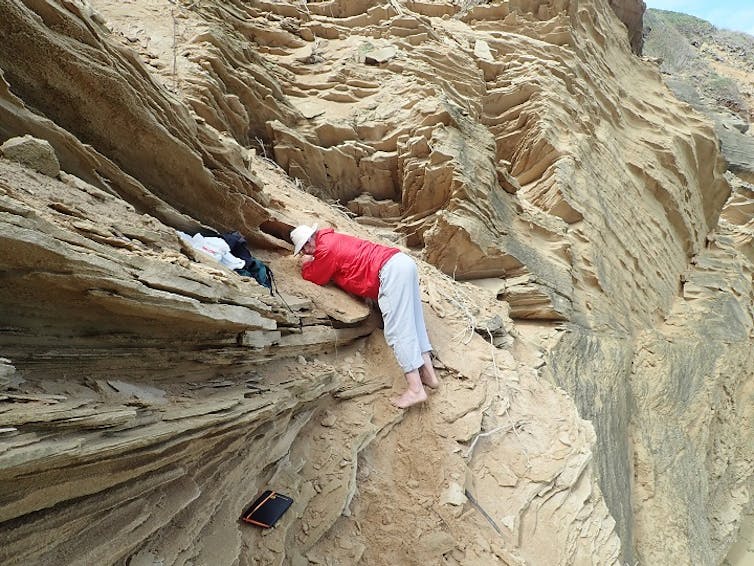

Some of our sites were tough to reach. For example, one site was among high, brittle cliffs on the under-surface of the ceiling of a tiny overhang.

Author supplied

Initially only two tracks were visible. But, following some excavation we identified a total of five tracks and created enough space to take photos for photogrammetric studies that enabled us to create a 3D digital model of the trackway which otherwise could not be adequately studied.

What do these large tracks tell us? Their outer digits showed some curvature, strongly suggesting that the trackmaker had webbed feet. But the tracks couldn’t be definitively linked to those of any member of southern Africa’s existing avifauna.

These findings raise two possibilities. The first, in line with evidence from elsewhere in the world, is that some Pleistocene bird species were larger than their modern counterparts – they got smaller over time.

The second possibility is of previously unsuspected Pleistocene avian extinctions. We could postulate, for example, that a large freshwater bird species may have been driven to extinction by a change in climate that we know inundated the abundant wetland habitat that previously existed on the adjacent Palaeo-Agulhas Plain.

The Pleistocene body record fossil does not provide any such evidence. It extends back to about 80,000 years ago and most of the tracksites we have documented appear to be from the 130,000 to 90,000 year range. So it’s plausible that Pleistocene avian extinctions predated any evidence that may be available through the skeletal record.

Easily lost

Though the sites we’re exploring are ancient, they are also ephemeral. Tracks are made on a dune, covered by another layer of sand, and then buried by 100,000 years or more. Once exposed through the forces of erosion they are destined to disappear within a very short period of time, also through erosion or other natural forces – and sometimes, regrettably, through graffiti on the rocks.

The splendid fossil flamingo tracksite is an unfortunate example of this. It was obliterated by a powerful storm surge in the winter of 2020. Nonetheless, the photogrammetric record that we obtained ensures that this unique surface has not been lost to science, and it would be feasible to create an exact replica.

Still, the message is clear: we need to be vigilant, and to keep on searching, exploring, and documenting – because like their mammal and reptile counterparts, fossil bird tracks have a lot to teach us.![]()

Charles Helm, Research Associate, African Centre for Coastal Palaeoscience, Nelson Mandela University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.