Elizabeth Heineman, University of Iowa

Hugh Hefner’s death has reopened bitter debates about his place in history.

Many obituaries in the mainstream media have described him as a sexual liberator. Feminists and conservatives, however, have employed far harsher terms, noting that he drugged, demeaned and essentially imprisoned women in his Playboy Mansion in order to live out the fantasy he marketed.

Hefner’s conduct looks particularly grim when compared to that of the woman sometimes described as the German Hugh Hefner: Beate Uhse, who also rose to prominence after WWII and became a household name in Germany and Europe. (She died in 2001.) As the author of a book on Germany’s most famous erotica entrepreneur, I am struck by how radically the early stages of her career deviated from Hefner’s.

Each made sexuality into big business. But whereas Hefner “liberated” men to live out their sexual fantasies free of financial or emotional responsibilities to women, Uhse urged mutual pleasure built on communication and sexual education – as well as sex toys, skimpy lingerie and titillating photos.

A different vision of sex – with a focus on women

Beate Uhse was born in 1919 – seven years before Hefner – to one of Germany’s first female physicians. She had an enlightened upbringing: Her parents educated their children about sex and set no limitations on their daughters’ ambitions. Beate became a pilot – an unusual profession for women even today – and during World War II she flew for the Luftwaffe. By war’s end she was a widow, a mother and a refugee from Soviet-occupied East Germany.

Dutch National Archives

To survive in West Germany’s postwar “hunger years,” she turned to the black market. A self-penned guide to the rhythm method – avoiding sex during a woman’s most fertile days – found eager buyers.

Uhse’s second career was born.

Within two decades, her firm, the eponymous Beate Uhse, would become the largest erotica enterprise in Germany. Today it remains Europe’s biggest erotica business.

In the 1950s and 1960s, Uhse battled restrictive legislation, powerful churches and conservative social mores. So did Hugh Hefner. But Uhse’s vehicle was not a magazine peddling nude women. Rather, it was a mail-order business selling all manner of goods: condoms, sex aids (today we call them “toys”), self-help books, erotic literature, aphrodisiacs, lingerie, gag items – and, yes, photos of scantily-clad women.

Playboy encouraged unrestrained male pleasure, the type that didn’t require financial or emotional obligations. Beate Uhse, on the other hand, encouraged good sex as a necessary part of committed and loving relationships, with special attention to women’s desires.

Hefner presented himself as the embodiment of the lifestyle he promoted: a bathrobe-clad swinger surrounded by Playboy bunnies. Uhse presented herself as the embodiment of the lifestyle she promoted: a mother of four children who understood women’s problems and could help to communicate them to men.

Ending ‘sexual misery’ in postwar Germany

In promoting her business and cultivating her image, Beate Uhse drew on the tradition of “marital hygiene,” which had emphasized companionate marriage and sexual health in Europe and North America starting in the 1920s.

Sex reformers in the 1920s felt that ending “sexual misery” entailed breaking down barriers of shame and improving sexual education. Doing so would improve public health, marital happiness and families’ economic stability.

The need was even more intense after World War II. Due to wartime separation, millions of Germans had lost (or never established) good patterns of communication with their partners. A great many had experienced militarized sexual violence, either as perpetrators, victims or eyewitnesses. Unplanned pregnancy could be disastrous in the landscape of hunger and homelessness that followed the war.

Beate Uhse promised to remedy this sexual misery. Using exquisitely delicate language, her catalogs diagnosed a range of sexual problems and offered solutions through consumption.

She hinted that men who rushed lovemaking because their minds were cluttered by work would disappoint their wives. (An erotic novel might get them into the mood.) She wrote that without contraception, women would seek unsafe abortions – and would also be unable to climax due to fear of pregnancy. (Couples might consider a wide array of contraceptives.)

If a woman appeared “frigid,” it was probably because her husband didn’t know how to make love to her. He might not even know that she, too, was capable of climax. (He should read a sex manual, and perhaps try a device to increase the stimulation his wife experiences during intercourse.) And if a man climaxed too quickly, he would frustrate his wife, whom nature had equipped to take more time to reach orgasm. (An ointment to prevent premature ejaculation would help.)

A savvy businesswoman

Did Beate Uhse ignore men’s sexual desires, which may not always have been directed at monogamous relationships? Of course not. Men made up the majority of her customers, and Uhse knew perfectly well that they didn’t use her products only with their wives.

Yet however pleasurable illicit uses of risqué photos and condoms may have been, such activities did not create the happy marriages that most men also wanted. Some men, Uhse knew, rejected illicit sex and “obscenity” outright, but cared about their wives’ happiness. Worst of all, Uhse understood, men’s own guilt compounded the problem. Many liked arousing images, accepted nonmarital sex, and sought pleasure for themselves and not just for their partners. But they felt guilty because it was so hard to interpret such pleasures as legitimate. Emphasizing marital hygiene and good sex for women worked for men too: It offered an alternative not only to the condemnatory language of decency advocates but also to the “dirty talk” of the military and the pub.

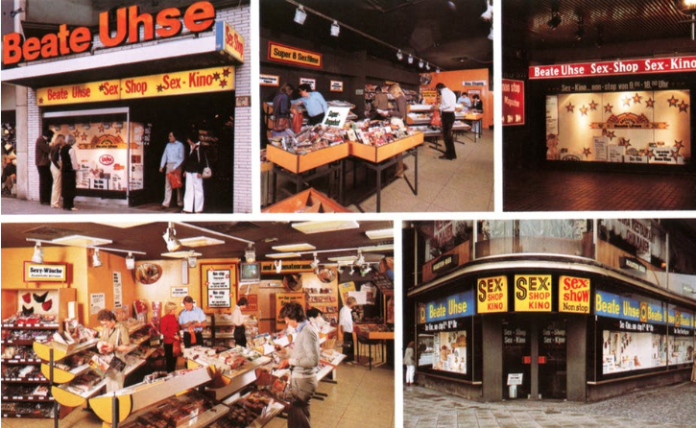

With time, Beate Uhse’s business changed. In the early 1960s, her firm pioneered brick-and-mortar erotica shops. But the birth control pill put a dent in condom sales, while improved sexual education in the schools and the popular media decreased the need for basic self-help books. At the same time, West Germany’s prosperity and loosening regulations expanded the marketplace in pornography, which was legalized in 1973.

Beate Uhse was nothing if not an astute businesswoman, and she shifted course. Until the late-1960s, condoms and self-help manuals had constituted the business’s bread and butter. By the 1980s, Beate Uhse was best known as a peddler of porn.

A complicated legacy

Of course, Beate Uhse had plenty of critics.

In the early years, moral decency advocates had waged war on Beate Uhse and other erotica firms, successfully lobbying for stricter legislation to curb erotica firms’ activity. They were particularly irked by the fact that Beate Uhse, as a woman, stood openly behind her business: other erotica entrepreneurs at least had enough shame to maintain a low profile. Only good lawyers and sympathetic courts – Uhse lived in a liberal jurisdiction – enabled her business to survive long enough to see the moral purity movement’s power wane.

Beate Uhse’s turn to pornography, however, attracted a new class of critics: feminists.

In 1988, West Germany’s premier feminist monthly, Emma, published a cover story on Uhse. Its thesis was well-encapsulated in its opening paragraph: “At 25 she flew Stukas to the front. For Hitler’s Luftwaffe. At 69 she sells women. For 90 million a year.” The journal acknowledged Uhse’s pioneering role, but with a sinister twist: “Beate Uhse is an emancipated woman. One who emancipated herself on women’s backs.”

Despite Emma’s unremitting hostility to porn, some feminists in Germany, as in the United States, created feminist pornography and opened feminist sex shops. Beate Uhse was not among them. Her porn was distinctly mainstream, adopting clichés and cinematic techniques aimed at a straight male audience, such as male ejaculation as the pinnacle of sexual satisfaction and a narrow range of female body types.

Nonetheless, we can see the impact of Beate Uhse’s products and the firm’s language of sexual mutuality and equality.

West German women’s resistance to the birth control pill (relative to their American counterparts) didn’t just reflect their concern about its medical side effects. It also reflected an awareness that there was an easily available alternative in the form of condoms – and the belief that one might reasonably expect men to use them. When, in 1964, male student radicals put images of nude women on the covers of their magazines in order to increase circulation, their female counterparts were quick to object. Rather than having to create a feminist critique from scratch, they had expectations regarding mutual respect that were now being violated.

Both Hugh Hefner and Beate Uhse were enormously influential. But it was always a stretch to imagine Hugh Hefner as a liberator of women’s sexuality.

![]() We don’t need to honor a serial abuser to acknowledge an erotica entrepreneur who battled the courts and conservative mores to create a more liberated sexuality. Beate Uhse waged the same battles, but shaped a sexual consumer culture grounded in female pleasure and mutual harmony. And then she turned to mainstream porn. If we want to ponder the true ambivalence of sexual consumer culture, Beate Uhse is the place to look.

We don’t need to honor a serial abuser to acknowledge an erotica entrepreneur who battled the courts and conservative mores to create a more liberated sexuality. Beate Uhse waged the same battles, but shaped a sexual consumer culture grounded in female pleasure and mutual harmony. And then she turned to mainstream porn. If we want to ponder the true ambivalence of sexual consumer culture, Beate Uhse is the place to look.

Elizabeth Heineman, Professor of History and Gender, Women’s, and Sexuality Studies, University of Iowa

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.