Mary Kate Cary, University of Virginia

Boy, do I miss Jim Lehrer.

I thought of the late PBS anchor and legendary presidential debate moderator fondly while watching the last two Democratic debates in Charleston and Las Vegas. The constant interruptions, the lack of decorum and the complete disregard for time limits on candidates’ answers all worked to cause viewers like me to hope Lehrer had faked his own death and would come walking back on stage.

Why couldn’t a combined total of 10 moderators at two debates keep control of seven candidates?

With the next Democratic debate coming this weekend, the moderators from CNN and Univision could learn a few lessons from a pro like Lehrer.

‘Clarify that statement’

Dubbed by Politico as the “Master of Moderation,” Lehrer moderated 12 presidential debates between 1988 and 2012, the most of anyone in American history.

Two years ago, the University of Virginia’s Miller Center, a nonpartisan think tank which specializes in presidential scholarship, held a workshop for Senior Fellows – including me – to learn how to moderate debates and panel discussions. Lehrer, a long-time Miller Center board member, offered to give us his best advice.

Three hours later, I had taken pages of notes.

“To me, moderating a presidential debate has become like riding a bike,” Lehrer said, acknowledging his decades of being at center stage every four years. “But I realize not everyone knows how to ride that bike, so I’m going to spend the next few hours teaching you what I know.”

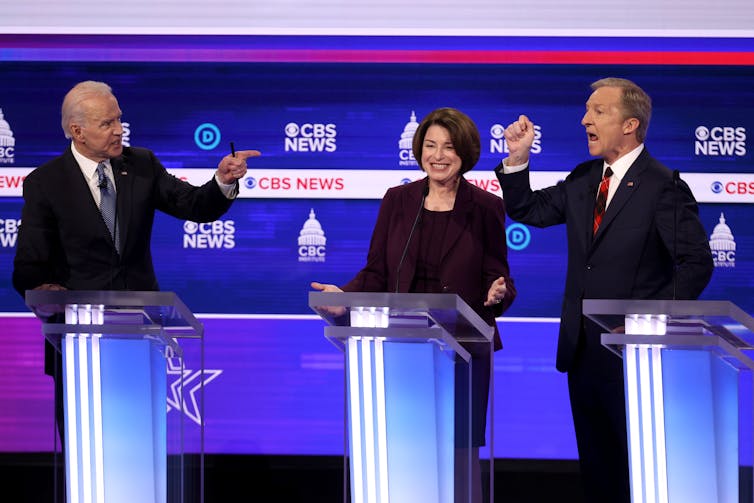

Getty/Win McNamee

Got a candidate who is taking more time than others? Ask more questions of the others to maintain the perception of fairness. If you ask long involved questions, he advised, you’ll get long involved answers – and the problem of imbalance arises from the start.

“If a candidate says, ‘My answer has seven parts,’ you say: ‘Great, give me the first three.’”

Is a candidate attacking the moderator? Turn the other cheek, smile and don’t take the bait. “If the moderator gets drawn into a fight, the moderator always loses,” Lehrer warned us.

Think a candidate isn’t telling the truth? Don’t yell “Liar!” Keep from reacting at all. Then try: “Based on my knowledge, I want to ask you to clarify that statement.”

Battle plans ‘out the window’

Before every debate, Lehrer said, he would look into a mirror offstage: “It’s not about me,” he’d tell himself. He told us to use our knowledge to shine a light on other people’s knowledge, not our own.

He was such a humble man, in fact, that he told us that if you heard anyone quoting the moderator at the end of a debate, you’d know the moderator had failed.

No need to preface your questions with a lead-in or even worse, your own opinion. Just get right to the point: “Do you agree?” “Do you think that’s right?” “What would a good deal look like to you?”

Do your homework, and have more questions than you think you’ll ever need. Know everything there is to know about the people on stage and what their positions are. Map out in advance where you want the discussion to go.

“Have a battle plan,” he said with a wry smile, “but know it’ll go out the window once the first bullet is fired.”

Tricks for enforcing the rules

But Lehrer’s best advice was how to create an engaging, civil conversation on stage in which everyone feels they have been heard.

The first step of the plan is to take a few minutes at the start of a debate to make sure the rules are clear – how the questions will be given, how much time each candidate has to answer, how rebuttals will be handled and the like.

He’d tell candidates that in order to help them abide by the rules, a bell or warning lights would signal when their time was expiring. If they don’t heed the warning, the moderator will have to intervene and move on to the next candidate.

The second step: Even though it may seem mundane to the audience, it’s crucial to explain those rules in front of the crowd. You want the audience to know the rules of the game.

That way, when the candidates start breaking the rules, the audience immediately knows it. And the audience will subconsciously give the moderator permission to act.

“Bring the audience in on the rules,” Lehrer said, “because then enforcement will be easier.”

Finally, Lehrer shared what he’d say to candidates beforehand:

“Don’t talk at the same time, because no one gets heard.”

“We are not here to have a fight, we are not here to filibuster.”

“My job is to help people understand your position.”

And my personal favorite: “I will be fair.”

That’s why I miss Jim Lehrer.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]![]()

Mary Kate Cary, Adjunct Professor, Department of Politics and Senior Fellow, UVA’s Miller Center, University of Virginia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.