Lisa Coulthard, University of British Columbia

How should we think about the late Canadian filmmaker Norman Jewison’s legacy?

Cinema studies professor Bart Testa’s opening for his insightful chapter “Norman Jewison: Homecoming for a ‘Canadian Pinko’” argues that “Jewison has not been highly regarded or carefully discussed by film critics, Canadian or American.”

This statement could not ring more true than on the occasion of Jewison’s death.

Although there are numerous obituaries listing Jewison’s high-profile films, including Fiddler on the Roof, Moonstruck and In the Heat of the Night, not all discuss the prolific nature and significance of Jewison’s career.

With more than 40 films and television shows, Oscar, BAFTA and Golden Globe nominations and awards — and his establishment of the Canadian Film Centre — Jewison’s legacy is notable.

And yet, as Testa’s analysis suggests, scholarly and critical attitudes towards Jewison have sometimes been marked by indifference or even dismissal for his blend of commercial and populist success.

Jewison has always been seen as a good director who made many enjoyable, socially pertinent films. But he should also receive his due as a varied filmmaker who succeeded in multiple genres, focused on actors and scripts and was innovative in musical and social justice genres.

Effective writing, strong performances

A Torontonian by birth who got his start in Canadian television, Jewison honed his skills working on Tony Curtis and United Artists comedies.

He quickly turned to serious drama with In the Heat of the Night before making hit musicals Fiddler on the Roof and Jesus Christ Superstar.

Canadian cultural historian George Melnyk characterized Jewison’s work as “generally indistinguishable from other well-made mainstream American cinema,” commenting on a perceived lack of an auteurist signature.

Director Quentin Tarantino assessed F.I.S.T. as a “bland epic” that plays like “a truncated ‘70s television miniseries”.

In director Douglas Jackson’s National Film Board of Canada documentary Norman Jewison, Film Maker (1971), Jewison notes that he is “not an intellectual filmmaker” but an “emotional one.”

Although this description might seem self-evident to anyone familiar with Jewison’s many emotionally resonant films, it indicates an approach to film-making that focused on effective writing (many of his films were based on plays or Broadway adaptations) and strong performances.

As is evident in the Jackson documentary, filmed during the making of Fiddler on the Roof, Jewison was hyper-focused on the nuances, details and impact of actors’ performances. The documentary shows Jewison revelling in the minutiae of performance — where the pause, breath or accent hits in a line delivery.

This focus perhaps comes from his early training as an actor or his entry into comedy film-making, where timing is always everything. It’s a detail we see throughout Jewison’s films. https://www.youtube.com/embed/gsDP-90j9x8?wmode=transparent&start=0 Trailer for ‘Fiddler on the Roof.’

Big stars, film newcomers

Jewison was able to manage big-star personalities such as Rod Steiger, Al Pacino, Sylvester Stallone, Nicholas Cage, Denzel Washington, Danny DeVito, Steve McQueen, Carl Reiner and Cher and direct them to more nuance.

At the same time, he was able to draw out strong performances from actors who were cinematic newcomers like Chaim Topol and Ted Neeley).

Testa focuses on Jewison’s politics (liberal, anti-establishment, leftist) and his place in the industry of film-making at such a crucial time in cinematic history when the studio era was ending and independent filmmaking was on the rise.

Often working as both producer and director, Jewison had artistic freedom but also anxieties about budget. In the Jackson documentary, Jewison describes these as particularly “Canadian” concerns, but they were considerable for a director who worked in international locations and took risks on unknown actors the way he did.

Although award-winning and popular, Jewison was also on the edge of Hollywood: he was not American and not part of the film-school generation or Hollywood renaissance (1967-74).

The title of his 2004 autobiography in some ways says it all: This Terrible Business Has Been Good to Me. https://www.youtube.com/embed/hIe8GA3VvYg?wmode=transparent&start=109 Trailer for ‘Jesus Christ Superstar.’

Jesus Christ Superstar’s cult fandom

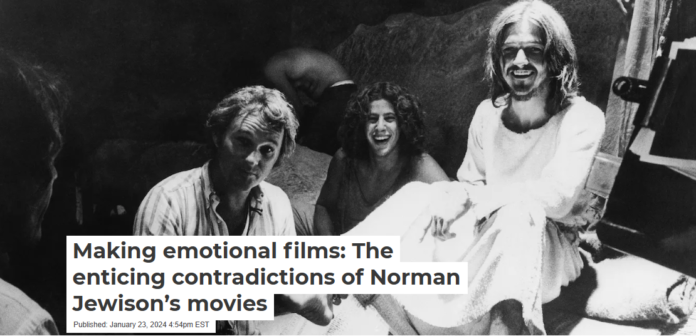

Although only passingly mentioned in some obituaries, I believe Jesus Christ Superstar most clearly represents these contradictory strands of Jewison as a director.

At the time of the movie’s filming, Jewison had been nominated for and won key awards, making a name for himself in American cinema.

It was nonetheless a risky project: a rock opera starring unknowns, filmed on location in Israel and featuring a cast of actors with no or very little film experience.

It was also plagued by budget issues and controversy. Surprisingly, it was not only a box-office success at the time, but continues to have a cult following that extends to the star of the film as well.

The fandom for a film like Jesus Christ Superstar show that assessments of Jewison as an indistinct but adequate filmmaker are misguided.

My early exposure to the film was a chance viewing on TV with my father when I was about 11. My parents were not religious, not intellectuals and not cinephiles, but Jesus Christ Superstar quickly became a family favourite.

At a time when theatres host group sing-alongs for films like Grease and The Sound of Music, my particular set of friends opt for sing-along parties for Jesus Christ Superstar.

Jewison’s ultimate legacy

This tension between cult, critical and popular appeal alongside a scholarly disregard is in fact Jewison’s most prominent legacy.

Bridging American, Canadian and English systems and industry cultures, Jewison can be viewed less as a merely skilled, socially minded filmmaker, and more as an enticing contradiction.

He was both an insider and an outsider in terms of the industry, both Canadian and American in terms of sensibilities, both mainstream and progressive in terms of politics and independent and commercial in terms of film-making.

Perhaps Jewison’s distinctive indistinction is precisely his legacy. These contradictions allow for what Jewison notes in the Jackson documentary as an essential directorial quality — a lack of ego.

And in an industry full of ego, this distinction allowed him to be, as Denzel Washington says, “a real actor’s director,” shaping and nudging star performances in subtle and effective ways, drawing out what he saw as the emotional core of his films.

Lisa Coulthard, Professor, Department of Theatre and Film, University of British Columbia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.