Scott Denning, Colorado State University

Editor’s note: A new study by scientists in the United States, China, France and Germany estimates that the world’s oceans have absorbed much more excess heat from human-induced climate change than researchers had estimated up to now. This finding suggests that global warming may be even more advanced than previously thought. Atmospheric scientist Scott Denning explains how the new report arrived at this result and what it implies about the pace of climate change.

How do scientists measure ocean temperature and estimate how climate change is affecting it?

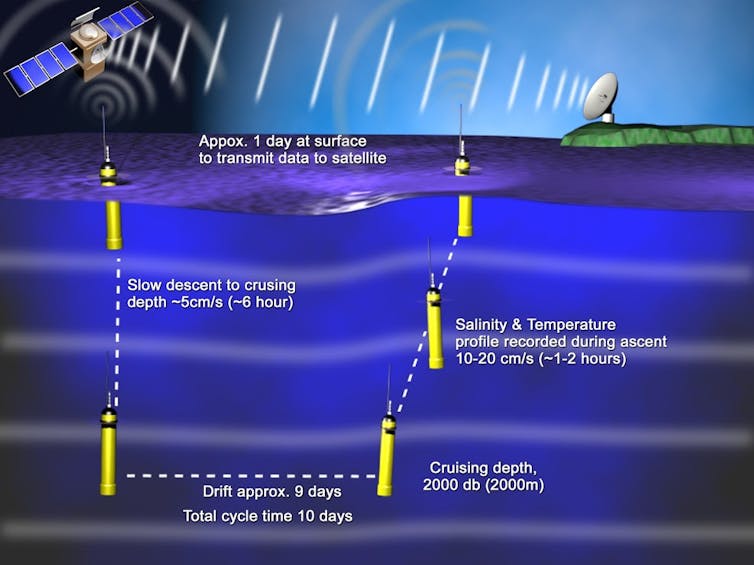

They use thermometers attached to thousands of bobbing robots floating at controlled depths throughout the oceans. This system of “Argo floats” was launched in the year 2000 and there are now about 4,000 of the floating instruments.

About once every 10 days, they cycle from the surface to a depth of 6,500 feet, then bob back up to the surface to transmit their data by satellite. Each year this network collects about 100,000 measurements of the three-dimensional temperature distribution of the oceans.

The Argo measurements show that about 93 percent of the global warming caused by burning carbon for fuel is felt as changes in ocean temperature, while only a very small amount of this warming occurs in the air.

International Argo Program, CC BY-ND

How dramatically do the findings in this study differ from levels of ocean warming that the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has reported?

The new study finds that since 1991, the oceans have warmed about 60 percent faster than the average rate of warming estimated by studies summarized by the IPCC, which are based on data from Argo floats. This is a big deal.

Most of the difference comes from the earliest part of this period, before there were enough Argo floats in the oceans to properly represent the three-dimensional distribution of global water temperatures. The new data are complete all the way back to 1991, but the Argo data were really sparse until the mid-2000s.

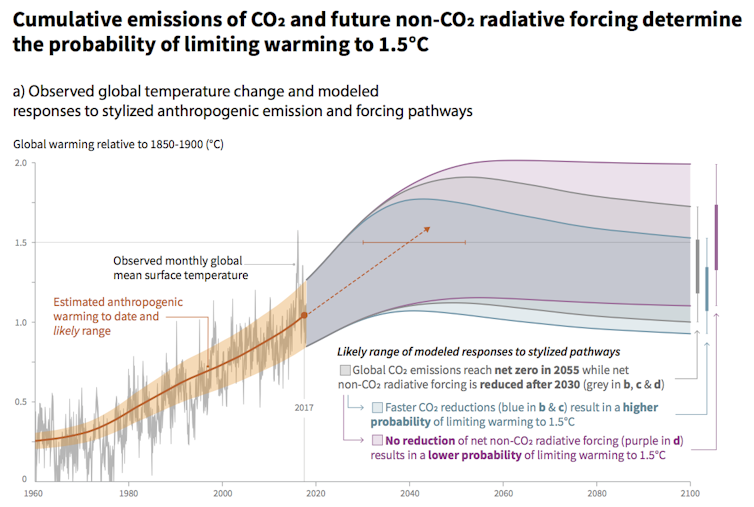

The implication of faster ocean warming is that the effect of carbon dioxide on global warming is greater than we’d thought. We already knew that adding CO2 to the air was warming the world very rapidly. And the IPCC just warned in a special report that limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) above pre-industrial levels – a target that would avert many extreme impacts on humans and ecosystems – would require quickly reducing and eventually eliminating coal, oil and gas from the world energy supply. This study doesn’t change any of that, but it means we will need to eliminate fossil fuels even faster.

IPCC, CC BY-ND

What did these researchers do differently to arrive at a higher number?

They have measured tiny changes since 1991 in the concentrations of a few gases in the air – oxygen, nitrogen and carbon dioxide – with incredibly high precision. This is really hard to do, because the changes are extremely small compared to the large amounts already in the air.

Some of these gases from the air dissolve into the oceans. The water’s temperature dictates how much it can absorb. As water warms, the amount of a gas that can dissolve in it decreases – that’s why a soda or beer left open on the kitchen table goes flat. That same temperature dependence allowed the scientists to calculate total changes in global ocean heat content from 1991 to now, just using very precise measurements of the air itself.

If this study is accurate, what does it suggest we should expect in the way of major climate change impacts in the coming decades?

This study did not address climate impacts, but they are already well known. As the world warms, more water vapor evaporates from both oceans and land. This means that when big storms develop, there’s more water vapor in the air for them to “work with,” which will produce more extreme rain and snow and resulting winds.

Greater warming will mean increased water demand for crops and forests and pastures, more stress on irrigation and urban water supplies, and reduced food production. More water demand means more forest fires and smoke, shorter winters with less mountain snowpack, and increased stress on ecosystems, cities and the world economy. Because of these effects, nearly every government in the world has committed to rapid emissions cuts to limit global warming.

What this study suggests is that the climate is more sensitive to greenhouse gases than we previously thought. This means that in order to avoid the worst consequences of climate change, emissions will need to be cut faster and deeper.

How will we know whether these findings hold up?

There are other groups making precise gas measurements, and many of them have data going back to the 1990s. Others will repeat the analyses made by these authors and check their results. There will also be careful work to reconcile the increased warming rate of the oceans with the Argo temperature data, the surface air temperature record, atmospheric data from balloons and measurements made from satellites. The real world must be consistent with all of the observations taken together, not just a subset.

This study very cleverly used data from the composition of the air itself going back nearly 30 years. We didn’t have Argo floats back then, but air samples are still available that can be analyzed decades later. Using a longer record of warming is much better for estimating the rate, because it’s less sensitive to year-to-year variations than a shorter record.

These scientists have given us a new and independent way to assess the sensitivity of long-term global warming to changes in atmospheric CO2 levels. I expect the findings will indeed hold up, and that we will be hearing a lot more about this new method in the future.![]()

Scott Denning, Professor of Atmospheric Science, Colorado State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.