Vicki Crawford, Morehouse College

For the past 11 years, civil rights historian Vicki Crawford has worked as the director of the Morehouse College Martin Luther King Jr. Collection, where she oversees the archive consisting of iconic sermons, speeches, writings and other materials belonging to King.

Few archives of historical papers compare with the importance of the Morehouse King Collection. Aside from King’s life, the collection chronicles many of the major events that occurred during the civil rights movement.

Since joining Morehouse, Crawford says she especially enjoys introducing younger generations to King and helping them understand the powerful lessons of the struggle for social justice, particularly how everyday people organized and worked for social change.

Of the countless things she has seen, read and learned about King’s theology and civil rights activism, Crawford details five of the countless aspects of his life that stand out.

An avid reader

King read voraciously across a wide range of topics, everything from the “The Diary of Anne Frank” to “Candide.” Of course, he also read about theology and religion and philosophy and politics. But he especially enjoyed literature and the works of Leo Tolstoy.

The Morehouse College Martin Luther King Jr. Collection includes approximately 1,100 books from King’s personal library, many with his handwritten notes throughout.

Some of the titles: “Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi,” “Complete Poems of Paul Laurence Dunbar,” “Deep River: Reflections on the Religious Insight of Certain of the Negro Spirituals” by Howard Thurman, “Invisible Man” by Ralph Ellison, “Kinfolk” by Pearl S. Buck and “Moral Man and Immoral Society: A Study in Ethics and Politics” by Reinhold Niebuhr.

Others include “Frederick Douglass, My Bondage and My Freedom,” “Silent Spring” by Rachel Carson, “Prison Notes” by Barbara Deming, “Killers of the Dream” by Lillian Smith and “Here and Beyond the Sunset” by Nannie Helen Burroughs.

A celebrated writer

Following the 381-day Montgomery bus boycott, which started in 1955, King became a national figure whose ideas and opinions were heavily sought out by book publishers, newspapers and magazines.

He became a prolific writer and authored countless letters – arguably the most famous being “Letter from Birmingham Jail” – as well as several books, among the most notable “Why We Can’t Wait” and “Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community?”

But many Americans may not know that he wrote a regular column in Ebony magazine, the leading black national publication at the time. In his “Advice for Living” column, he took questions from readers and addressed a wide range of subjects, including personal questions about marital infidelity, sexual identity, birth control, race relations, capital punishment and atomic weapons.

A follower of Gandhi

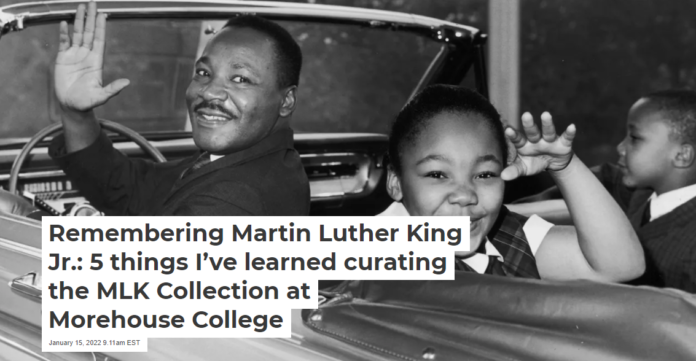

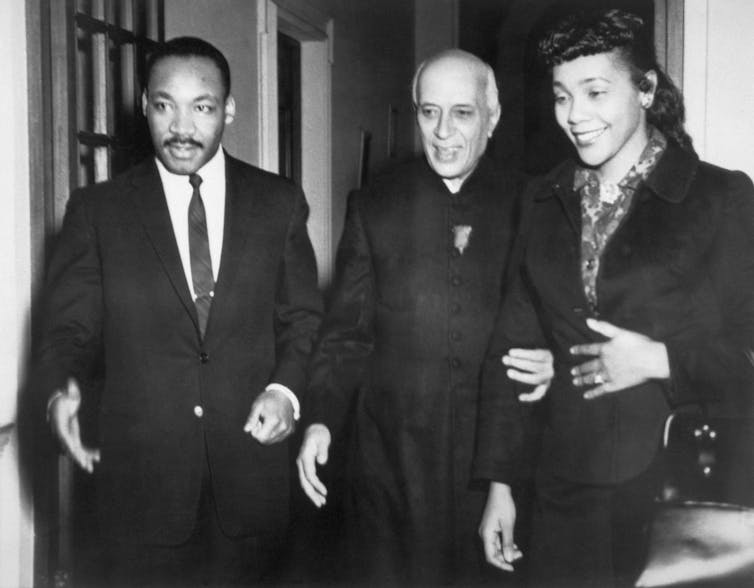

In 1959, King and his wife visited India, where King’s commitment to the nonviolent teachings of Gandhi expanded and deepened. King always carried a note with him on a scrap of paper that read “Gandhi Speaks for Us. …”

A lover of music

Music formed an important part of King’s life, beginning with his childhood experiences in Ebenezer Baptist Church, where his mother, Alberta Williams King, was the church organist. Alberta King introduced young M.L., as he was called, to music as a child. He later sang solos and sang with the church choir. While a student at Morehouse College from 1944 to 1948, Martin Luther King Jr. sang in the renowned Morehouse College Glee Club as well as the Atlanta University-Morehouse-Spelman Chorus.

Following his marriage to Coretta Scott in 1953, King expanded his world of music even more. He met Coretta in Boston, where she was studying to become a concert soprano at the New England Conservatory of Music. Coretta introduced King to classical music. He came to appreciate both sacred and secular music and enjoyed jazz and blues as well.

Some of King’s favorite hymns and gospel songs included “Take My Hand, Precious Lord,” “How I Got Over,” “Thank You, Lord” and “Never Grow Old.”

King was also a friend to Aretha Franklin and her father, the Rev. C.L. Franklin, and gospel singer Mahalia Jackson. King felt that music was a powerful element in activism and nonviolent protest.

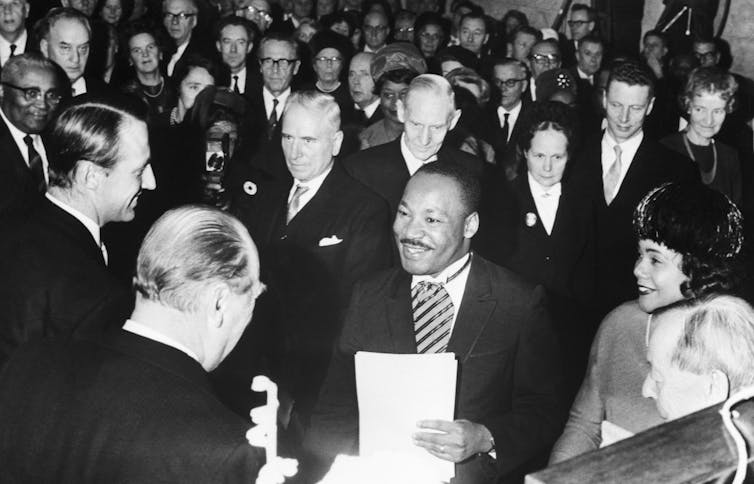

A Nobel Prize winner

At the age of 35, King was the youngest person, the third African American and the 12th American, to win the coveted Nobel Peace Prize for his steadfast belief that nonviolence was an integral part of obtaining full citizenship rights for Black people in America.

On Dec. 10, 1964, King announced that he was donating the Nobel Prize money to the civil rights movement.

[Explore the intersection of faith, politics, arts and culture. Sign up for This Week in Religion.]

Vicki Crawford, Professor of Africana Studies, Morehouse College

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.