Mark Partridge, The Ohio State University and Michael Betz, The Ohio State University

EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt is moving to repeal the Clean Power Plan as part of the Trump administration’s efforts to bring jobs and prosperity to communities that rely on the coal industry.

Our research focuses on determining which factors help create sustainable and prosperous regions, with a special focus on rural areas. In our view, Trump’s proposals will do little to help coal-dependent regions, and some will actually worsen their decline.

Communities that have historically relied on coal production, especially in Appalachia, have been suffering major economic and employment losses for decades. Today far fewer miners are needed to produce the coal that we consume, and alternative energy sources like natural gas, solar and wind have chipped away at coal’s cost advantage. Job losses in coal-reliant regions will only intensify as mining becomes more efficient and the nation takes steps to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Why has coal employment declined?

Coal industry employment has fallen from more than 500,000 workers in 1949 to around 50,000 workers today. Coal advocates contend that environmental regulations, such as the Clean Air Acts of 1977 and 1990, have caused hardship and job losses in many coal-dependent regions. But what these policies actually have done is change where coal is mined.

By requiring power producers to reduce sulfur emissions from electricity generation, the Clean Air Act triggered a shift in U.S. coal production from Appalachia, where coal is high in sulfur, to western states with abundant supplies of low-sulfur coal. However, overall U.S. coal employment was mostly unaffected by these regulations.

Instead, the decline in coal employment has been largely driven by market forces. The industry has invested in new mining methods and better machinery, so production requires far fewer coal miners.

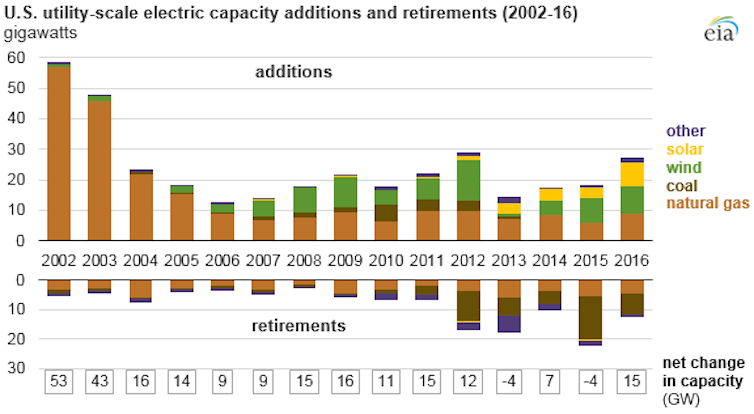

What’s more, coal is rapidly losing market share for economic reasons. Coal faces increased competition from shale natural gas, wind and solar. These fuels produce less pollution than coal and have become much cheaper in the past decade. In the past five years, nearly all new electricity generation capacity added in the United States was powered by natural gas, wind and solar. Nearly all retired plants were powered by coal. Natural gas generated more electricity than coal twice in 2015.

EIA

Mining jobs are primarily driven by market forces, so there is little that President Trump can do to bring coal mining jobs back without severely distorting energy markets. West Virginia Governor Jim Justice has proposed just that, urging the Trump administration to offer a US$15 per ton subsidy to power plants that burn coal from Appalachia.

Such a plan would be a boon for coal company executives and shareholders, but would do little for coal workers and communities. Using data from the Commerce and Labor departments, we calculate that in 2015 labor accounted for just 12 percent of the value of total coal mining output, down from 17 percent in 2001. This decline reflects increased use of machinery and mining methods and reduced need for workers.

How to help coal communities

To aid workers and communities where industries are declining, governments typically choose one of two approaches: offering direct support to those industries or funding investments in people and places.

Industrial support aims to maintain employment by providing subsidies or regulatory relief. Between 2009 and 2014 the Treasury Department invested nearly $80 billion in the auto industry to save General Motors and Chrysler from bankruptcy during a severe nationwide recession.

President Obama proposed a plan in 2016 called Power Plus that would have provided $2 billion in tax credits for installing carbon capture technologies on coal power plants, hopefully enabling them to continue production. These credits would have represented a subsidy to coal producers.

Peabody Energy/Wikimedia, CC BY

But industry support policies are unlikely to provide effective aid for workers and communities in coal-dependent regions for several reasons. First, any job increases from subsidies will be offset as mining operations become ever more productive and efficient.

Second, our research has shown that high levels of coal employment are associated with lower levels of entrepreneurship and higher levels of migration out of Appalachian regions as coal crowds out other types of businesses. This means that prolonging coal employment may actually slow the transition to other economic activities and reduce long-term economic growth.

Aid programs can invest in people and places through initiatives such as job retraining programs, small business support and funding for infrastructure. Ironically, President Trump has proposed to eliminate the Appalachian Regional Commission, a regional development agency that has been doing this very work for more than 50 years.

Last year the commission funded over 400 projects designed to build worker skills and promote entrepreneurship, infrastructure development and health. Our research shows that investments like this help poor regions grow. Defunding the commission would reduce economic opportunities and make local economies less resilient against economic downturns.

Trump’s 2018 budget proposal also cuts the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s discretionary spending by 21 percent and eliminates $231 billion from the Farm Bill over the next decade. These accounts do not just benefit farmers. More importantly, they support a broad range of rural economic development and health initiatives. The proposed cuts would unequivocally harm rural communities.

Office of Gov. Earl Ray Tomblin, CC BY-ND

Investing in quality of life

To spur economic development in lagging regions, it is helpful to consider what types of communities are likely to prosper in the future. Today we can predict that successful communities in 2040 or 2050 are likely be entrepreneurial and have well-educated workforces and high-quality schools.

Educated, highly skilled workers can live anywhere. To attract them, lagging regions need to offer a high quality of life and a clean environment. The Trump administration is moving in the opposite direction by weakening environmental regulation of the coal industry, which will make it harder for coal country to prosper in the long run.

We have found that entrepreneurship and creativity are key factors for promoting economic development in lagging areas of Appalachia. To foster them, aid programs should focus on improving quality of life and attracting new, highly skilled residents. One way to do so is by investing in natural resource amenities, such as abandoned mine cleanup. However, Trump’s budget request eliminates grants to Appalachian communities for economic development in conjunction with abandoned mine land cleanup.

Another strategy is investing in basic infrastructure, such as road maintenance, public schools and health care, freeing up local governments to invest local tax dollars in communities’ unique assets. The Appalachian Regional Commission already facilitates these types of programs. Substantially increasing the agency’s funding, rather then eliminating it, would be an effective way to help coal communities.

Editor’s note: This is an updated version of an article originally published on Feb. 15, 2016.

![]() Mark Rembert, Ph.D., contributed to this article.

Mark Rembert, Ph.D., contributed to this article.

Mark Partridge, Professor of Rural-Urban Policy, The Ohio State University and Michael Betz, Assistant Professor of Human Development and Family Science, The Ohio State University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.