Jay L. Zagorsky, Boston University

March Madness – the time when the best men’s and women’s college basketball teams challenge each other – is a made-for-television spectacle watched by millions. While March Madness has been around for decades, one of the tournament’s biggest changes happened in 2018, when the Supreme Court struck down the ban on sports betting.

Since then, legal sports betting has skyrocketed. Americans made US$120 billion of legal sports bets in 2023, according to the American Gaming Association, which promotes gambling. In 2024, the group predicts Americans will place $2.7 billion of legal bets on March Madness alone.

I am a business school professor fascinated by March Madness and sports betting. Studying sports betting has shown me how valuable it is for states short on cash. Unfortunately, it also has significant drawbacks, especially for gambling addicts and their families.

Why lawmakers love sports betting

As of March 2024, 38 states allow some form of sports gambling, and six more are debating the issue. State lawmakers are interested in sports gambling because they have a fiscal problem. State spending over time has increased in both absolute and per-person terms after adjusting for inflation.

While state spending is increasing, state revenue from so-called “sin taxes” has flatlined after adjusting for inflation. People are smoking and drinking less, reducing revenue from cigarette and alcohol taxes. Even lottery revenue has flattened out after growing strongly for decades.

Increased spending combined with a reluctance to raise taxes has led to a push to find new sources of revenue. That makes sports betting an appealing option to politicians.

The statehouse always wins

Billions of dollars are wagered on sports each year. More than 90% of the money bet goes to paying out winning gamblers. Gambling operators keep the rest, which they share with the states. The percentage kept, called the hold rate, has been steadily climbing over time, with 2023’s national average at 9.1% of the money bet.

State governments now collect about half a billion dollars each quarter, or about $2 billion a year, from sports gambling. That’s roughly one-fifth of that 9.1%.

If gamblers bet around $3 billion on March Madness, then states will pocket over $50 million dollars in extra revenue just from a three-week basketball tournament.

The ugly side of sports betting

Gambling is wonderful for state revenues and gaming-company profits. However, it has a dark side: While many people enjoy gambling, millions of Americans have a gambling problem.

Studies suggest between 1% and 2% of adults fall into this category. In Massachusetts, where I teach, a 2018 survey found that about 2% of adults were already problem gamblers, and a further 8% were at risk.

Meanwhile, the number of calls to the National Problem Gambling Helpline lasting more than a minute has increased sharply in recent years. While this doesn’t mean that problem gambling has become more common – among other issues, correlation isn’t causation – the increase very closely matches the steady rollout of online sports betting across the U.S.

Two possible policy solutions

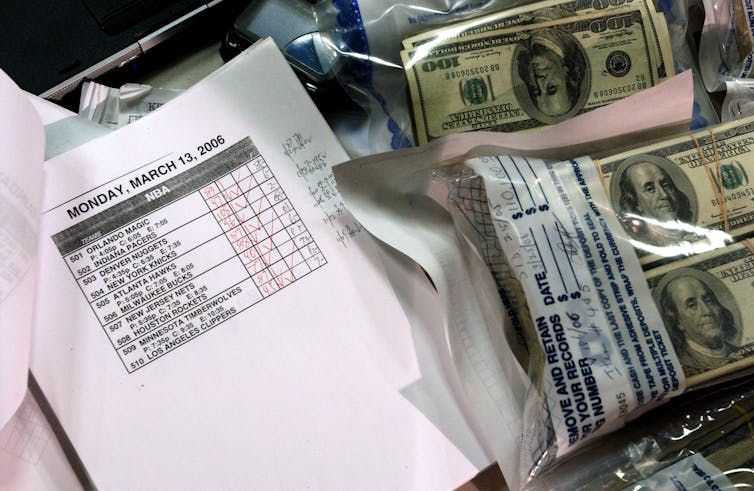

Betting on sports was illegal before 2018. This forced gamblers to either bet with a bookie or an offshore site. Betting with a bookie before 2018 was a relatively slow process. Gamblers typically needed to pay for their bets upfront with cash and ran the risk their bookie would be arrested or shut down.

Today, in-play or live betting is legal and almost instantaneous. Bettors sitting on their couches at home can make multiple types of bets, such as which player will make the first shot in a basketball game. In business terms, sports gambling went from extreme friction to a completely frictionless experience.

To reduce the harms of sports betting, I propose two ways to reinject friction into the system. The first is to prevent credit cards from being used for online gambling. While not every state and bank allows credit cards to fund a sports betting account, many do. Those credit cards that allow it often treat gambling payments as a cash advance, which is very costly.

The U.K. banned credit cards for remote gambling in 2020, noting that people who used credit cards to gamble were disproportionately likely to be problem gamblers. Australia has also banned online bets made with credit cards. A few U.S. states, such as Massachusetts and Tennessee, have also instituted these sorts of bans, but most have not.

The second idea, which I prefer, is to revert to common practice before 2018 of using cash to bet. The idea is simple. Anyone with an online gambling account would need to prefund their account with cash. Winners would never have to stop gambling.

Losers, however, would be forced to temporarily stop betting when their account runs out of money. Needing to take a break to go to a bank or simply pull money out of your wallet and hand it to someone would give people a chance to think about what they’re doing instead of being stuck in the moment of a bet-bet-bet mindset.

In theory, people could deposit cash into their accounts at any of the roughly 223,000 locations across the country that sell lottery tickets. To implement this idea, however, the federal government would need to change a law. Since 1955, it has imposed a special yearly tax of $50 on each person who accepts bets for profit.

The law exempts charities and state lotteries. This tax doesn’t raise much revenue already, since so few people are subject to it. It also reduces employment, as well as gambling companies’ interest in allowing in-person prefunding of accounts.

If you’re watching March Madness and betting on the tournament, I hope you win. But even if you don’t, at least your state government will.

Jay L. Zagorsky, Associate Professor of Markets, Public Policy and Law, Boston University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.