By Benjamin Poore, University of York

If you think of Sherlock Holmes, you will invariably think of London – to be precise, 221B Baker Street, which the great detective shared his adventures with Dr Watson. A new exhibition based, unsurprisingly, at the Museum of London, explores the links between the great detective and his Victorian centre of operations.

On show are typewriters and first editions, fingerprinting kits, and a plethora of examples of historical context, from disguises to drugs. But the exhibition also dovetails very well with the museum’s permanent collection, which tells the story of London from its origins, via its vast Victorian expansion, through its imperial pomp and into the past 60 years of London as a world city.

Sherlock’s story lies somewhere in this story, a little bit of fiction that nestles comfortably into historical fact. And it is a story that despite being so grounded in its contemporary locality, somehow translates fantastically to a 21st-century world city, too, as the slew of recent adaptations shows.

The reason why Sherlock Holmes has time travelled so well is that he has two very distinct sides. There’s his public role – which, in the original stories, sometimes involves him serving the interests of the British Empire, and then his private habits as a bit of a bohemian oddball, a professional maverick who operates on the outside of state bureaucracies.

Museum of London

Servant of Empire

The exhibition explains that “the Empire and its wars are ever-present in Holmes’s world”. And indeed, the Victorian Sherlock is ever-vigilant for those visitors who might bring disorder to the imperial capital’s streets. Watson is a veteran of “the second Afghan war”, as we’re told at the beginning of their first adventure A Study in Scarlet. The second book-length Holmes story, The Sign of the Four, concerns a deadly dispute over some treasure in India, against the background of the Sepoy Rebellion.

And it’s not only visitors from the empire who come to London with murder and criminality in mind. The canonical London of Holmes is beset with schemers from continental Europe, often aristocrats, with names like Count Negretto Sylvius, Baron Adelbert Gruner, and Baron Maupertuis. Holmes comes out of retirement to double-cross a German spy, Von Bork, on the eve of World War I in the story His Last Bow. It’s not hard to pick out a jingoistic, or at times even racist, subtext from Conan Doyle’s treatment of foreigners.

© Museum of London

Bohemian oddball

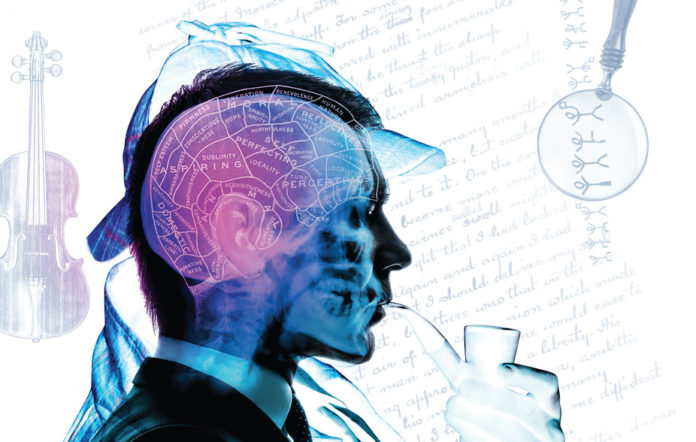

But another side of Holmes’s personality is his intense inner life, his ability to go for days without food and sleep when on a case, and the habits (cocaine, pipe-smoking, violin-playing) that support this activity. He has a series of “refuges” so that he can disguise himself and move about the city invisibly. He’s easily bored, and drawn to the unusual, the bizarre, cases with “features of interest”.

Despite these theatrical flourishes, the key to Holmes’s method is logic, deduction, scientific objectivity: he cannot solve mysteries in a state of ignorance and fear. He has to arm himself with knowledge and take London as he finds it. Sherlock seeks to know rather than to judge. He has his own moral code, which he applies even when that means bending the law.

Benedict Cumberbatch in Belstaff Coat, photograph by Colin Hutton.

© Hartswood Films

Modern Sherlock

The Sherlock in defence of the Empire is no longer a familiarity, and it is the oddball, the eccentric, who has stood the tests of time. The BBC’s Sherlock (Benedict Cumberbatch) may be cold and prickly, but he spreads his disdain to all equally – there is no hierarchy (apart from himself). Where knowledge is power, he can’t allow prejudice or lazy thinking to blind him to the evidence. Anticipating his return at the beginning of the most recent series, Sherlock talks of getting to know London again, “every quiver of its beating heart”.

The Sherlock of Elementary, CBS’s rival modern adaptation (played by Jonny Lee Miller), is more empathetic. He shows compassion for the disadvantaged, the underdog and those, like himself, recovering from addiction. They, in turn, also supplement his knowledge of the city.

Yet the legacies of empire are still apparent in these new series. Both the modernised Sherlocks end up working for British intelligence thanks to their brother Mycroft. And, in updating the Conan Doyle stories’ tales of imperial London, modern versions can still hit trouble. The BBC’s episode The Blind Banker came in for widespread criticism for its racial stereotyping.

Interestingly, in Elementary, the world city in which Sherlock operates is New York. This underlines a fundamental shift in economic and political power since the 19th century (plus, no doubt, a determined play for a somewhat larger American audience). And, we might ask, how long will New York remain the world city for? Which cities will the next generation of Sherlocks call home?

But perhaps there’s something about modernity itself that makes most big city dwellers feel, like Sherlock, that they walk the line between feeling hyper-connected to their surroundings and slightly alienated from them, too. Sherlock Holmes still embodies and captures that feeling for us, nearly 130 years on.

Sherlock Holmes: The Man Who Never Lived and Will Never Die is at the Museum of London until April 12 2015.

![]()

Benjamin Poore does not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has no relevant affiliations.

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Read the original article.