Jeff Borland, University of Melbourne

That COVID is hurting young workers more than older ones is widely recognised.

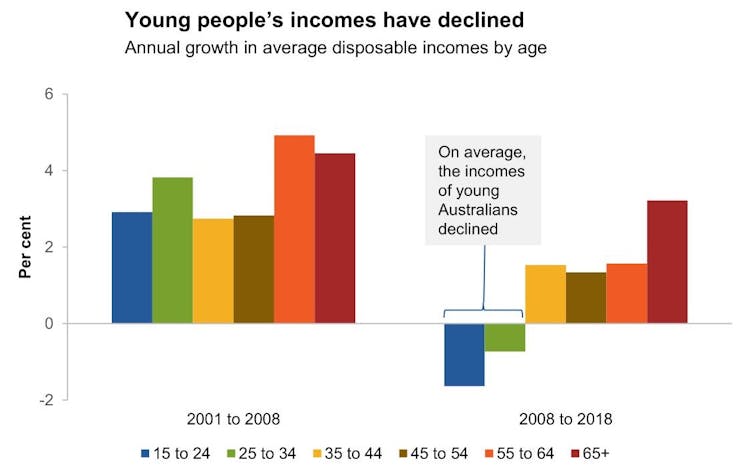

What’s less well known is that even before COVID-19, in the decade leading up to it, incomes for young people (aged 15 to 34) were falling in real terms while incomes for others continued to climb.

A graph that was created by the Productivity Commission for this morning’s report, Why did young people’s incomes decline? tells the story.

The report follows Monday’s report on declining job mobility for young people.

Commission estimates based on HILDA data

Disposable incomes are incomes after tax. The graph shows that in the years immediately after the Melbourne Institute’s HILDA Household Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia survey began asking the question, the real incomes of young Australians climbed in line with those of older Australians.

In the decade since 2008 they’ve gone backwards. Jennifer Rayner’s book Generation Less noted that the living standards of young and old were beginning to pull apart in ways that would strain common bonds.

Last year’s Grattan Institute report said today’s young were in danger of being the first generation in memory to have lower living standards than their parents.

Where the Productivity Commission study substantially advances our understanding is by presenting a detailed analysis of why incomes of the young have declined.

Read more:

It really is different for young people: it’s harder to climb the jobs ladder

It finds that young people’s real incomes have fallen since the global financial crisis mainly because they have fared worse in the job market.

Income can come from three sources – labour income, transfer income (government payments), and other income (which includes payments from non-resident parents and investment and business income).

The report finds that about three-quarters of the fall in real incomes of the young has been due to a decrease in their labour incomes (with the rest being due to a fall in other incomes).

Lower wage jobs, lower hours

The decline in labour income for the young is a result of both slower growth in hourly wages and of them working fewer hours. Hours of work have decreased as the young have shifted away from full-time towards part-time work.

With this shift has been a move to working for smaller firms, where wages are typically lower.

The next big question is what has caused the decline in labour incomes for the young.

Here, the Productivity Commission comes to the conclusion that it’s all about demand and supply.

Earlier work by Reserve Bank economists Natasha Cassidy and Zhoya Dhillion and my own work with Michael Coelli arrived at the same conclusion.

Since the early 1990s the proportion of the population wanting to work (the so-called participation rate) has been climbing.

Before 2008 and the global financial crisis that increase was outpaced by growth in the number of available jobs. Following the crisis the pattern reversed.

That has been bad news for the young. With the number of people wanting to work increasing faster than the number of available jobs, something had to give. It happened to be young people starting out in the labour market.

They found themselves crowded out from work and from the type of jobs they wanted (including full-time jobs) and having to accept lower-paid ones, with what turned out to be a a lower likelihood of later moving to a better job.

And less success at business

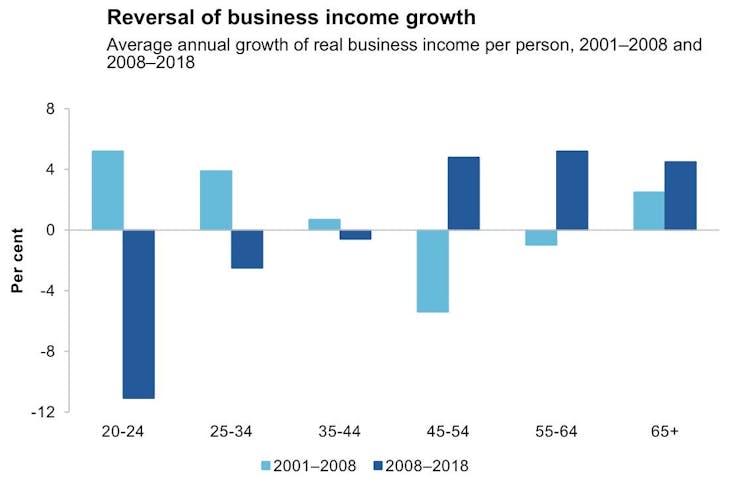

If all you knew was that young people’s income from paid work had declined, you might not be too worried. With all the high-tech start-ups involving young people, they must surely be able to make up those losses by striking out on their own and earning profits and business income.

The quashing of that idea is to my way of thinking one of the important findings of the Productivity Commission report.

It shows shows a large decrease rather than an increase in business income for the young, at a time when the business income of older Australians continued to climb.

The decrease happened both because after the global financial crisis young people were less likely to earn business income and because when they did it was more likely to come from low-paying industries.

Its a concerning finding for a nation pinning hopes on entrepreneurship, and an instance of where the report repays careful reading.

Lessons for COVID

It might seem as if analysing events in the decade after the global financial crisis is akin to studying ancient history, with the new COVID-19 labour market telling us more about what’s happening.

Nothing could be further from the truth.

Because it is about what happens to young people in a weakened labour market, the Commission’s report is replete with lessons for today.

It provides new perspectives on how the young are adversely affected, it tells us about how income support can help, and offers insights into how to make entrepreneurship better.

And it establishes unambiguously the case for worrying about the young in the time of COVID-19, all the more so because of what has happened in the leadup to it.![]()

Jeff Borland, Professor of Economics, University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.