Richard Gunderman, Indiana University

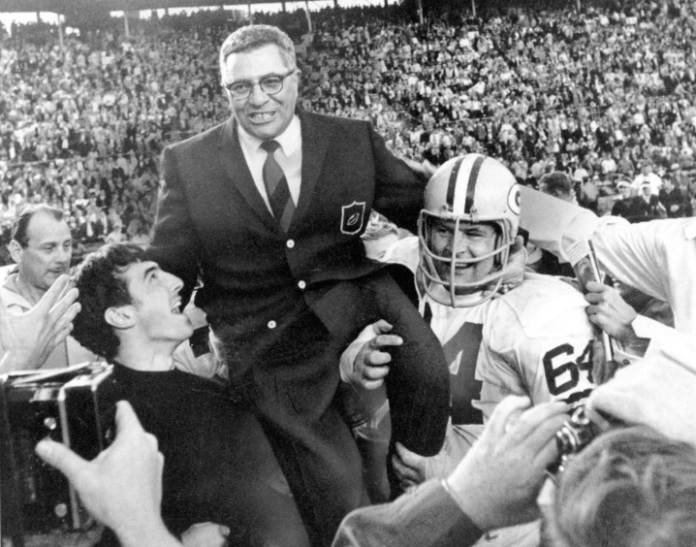

This Dec. 21 marks the 50th anniversary of the last football game Vince Lombardi ever coached. Remembered primarily as the helmsman of the Green Bay Packers during the 1960s and namesake of the Super Bowl trophy, Lombardi has been ranked as one of the top 10 greatest coaches in the history of American sports.

Like many greats, Lombardi considered coaching a form of teaching. As an educator who has spoken on Lombardi on numerous occasions, I find that his approach offers vital insights for today’s teachers, students and anyone who cares about educational excellence.

Education and early career

Since he died nearly 50 years ago, Lombardi may be unfamiliar to many. Born in Brooklyn to devoutly Catholic Italian immigrant parents, he originally intended to become a priest but instead attended Fordham University on a football scholarship. Though only 5’ 8″ and 180 pounds, Lombardi took his place as one of the “seven blocks of granite” of the team’s offensive line.

After graduating magna cum laude in 1937, Lombardi coached high school football and taught Latin and science. He subsequently moved on to assistant coaching positions at Fordham, West Point and the New York Giants.

In 1959, he became head coach of the Packers, a struggling team that had won only one game the previous season. With Lombardi at the helm, the team’s fortunes immediately changed, as they posted a 7-5 record and Lombardi won Coach of the Year honors. His teams went on to win five NFL championships, including the first two Super Bowls.

The Washington Redskins then recruited Lombardi as head coach, but the final game of the 1969 season turned out to be his last. He was diagnosed with colon cancer and died in 1970. Though he has been gone a long time, three of his core educational principles continue to resonate.

1. Put fundamentals first

Lombardi put fundamentals first. Each year at training camp, he would begin at the beginning, holding up a ball and telling the team, “Gentlemen, this is a football.” Lombardi knew that the will to win was not enough. To perform at their best, his players needed to know that they had prepared as thoroughly as possible to win.

Focusing on the fundamentals meant repetition. Although some of his players were the best in the game, he reviewed basic techniques of blocking and tackling and insisted on intense conditioning and drills.

And the same applied to his players’ characters. Lombardi relied on repetition to instill in every player such virtues as “hard work, sacrifice, perseverance, competitive drive, selflessness, and respect for authority.” These, he believed, were the fundamentals of excellence.

Such fundamentals are equally important for today’s teachers and students. At a time when standardized tests seem to tower over the educational landscape, abilities such as creativity, oral and written expression and collaboration – which are tending to be neglected – are more important than ever.

There is a big difference between selecting the “one best response” on a multiple-choice test and formulating a creative proposal, making a convincing case for it and drawing people together in pursuit of a shared goal.

2. Focus on effort

Lombardi is often quoted as saying, “Winning isn’t everything, it’s the only thing.” Whether or not Lombardi actually expressed such a view, it was not a “win at any costs” mentality. Unlike some notable competitors, the Green Bay Packers under Lombardi were never a “dirty” team that would do whatever it took to come out on top.

As Lombardi announced in his very first meeting with his Packers team,

Gentlemen, we are going to relentlessly chase perfection, knowing full well we will not catch it, because nothing is perfect. But we are going to relentlessly chase it, because in the process we will catch excellence. I am not remotely interested in just being good.

Recent scandals involving test cheating by teachers and bribery by parents serve as powerful reminders that an obsession with winning can eclipse education’s real goal.

3. Practice love

According to biographer David Maraniss, Lombardi once gave a pep talk to his team that began with an unexpected question: “What is the meaning of love?”

As one of the team members present later explained, “Coach didn’t want us picking on each other. Instead he wanted us thinking, ‘What can I do to make it easier for my teammate to help us win the game?’” The question was not, “How can I look better?” but “What can I contribute to make the team shine?”

When asked some years later about the source of his team’s excellence, Lombardi replied:

Teamwork is what the Green Bay Packers were all about. They didn’t do it for individual glory. They did it because they loved one another.

There are many bases on which we can appeal to contemporary teachers and students to do better. One is fear of the negative consequences of failure. Another is a desire to win recognition and rewards.

But perhaps the deepest and most enduring appeal is to love – a desire to make a difference in the lives of others and delight in seeing them flourish. Whether in sports or in life, when education is motivated by a desire to contribute, greatness becomes a possibility.

A great teacher

Lombardi collected many honors. In addition to winning widespread acclaim as one of the greatest coaches in the history of American sport, Lombardi received another award that probably meant more to him.

In 1967, Lombardi’s beloved alma mater, Fordham, awarded him its highest honor, the Insignis Medal, for being “a great teacher.” As Lombardi’s coaching life attests, there could be no greater purpose in life than helping human beings rise to their full potential.

Richard Gunderman, Chancellor’s Professor of Medicine, Liberal Arts, and Philanthropy, Indiana University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.