Kyle Greenwalt, Michigan State University

Pregnant teachers in classrooms are routine these days. But the law didn’t always protect expectant women in any workplace.

As part of her stump speech, Sen. Elizabeth Warren tells a story about being fired from her job as a speech pathologist for special needs children once she became pregnant back in 1971. Sharing this chapter in her history has prompted dozens of other women to speak out about their own similar experiences.

And while things have changed quite a bit, teachers are still confronting evolving restrictions on what they can or can’t do – inside and outside the classroom – typically based on moral grounds.

As a professor who instructs students who are training to become teachers, part of my job is to prepare them to uphold these ethical standards. I also have to explain that these standards are rarely clear and change all the time.

Nurturing teachers

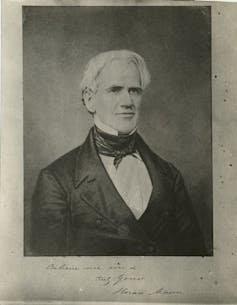

The lawyer Horace Mann, who became the first secretary of the Massachusetts State Board of Education in 1837, is best known for his leadership in bringing about the nation’s universal, taxpayer-supported, public education system. But that isn’t Mann’s only educational legacy.

In the early 1800s, teaching was largely itinerant work for young men who were preparing for careers in other professions. Mann believed teaching should become women’s work. Replacing stern school masters with gentle, nurturing school mistresses, he reasoned, would build public support for schools.

New York Public Library

In an 1844 report to the Massachusetts Board of Education, he praised teachers who were able to maintain a “beautiful relation of harmony and affection” with their students. He thought that their work was “better than parental.”

By 1870, 60% of the nation’s teachers were women. Over the next 50 years, the share of female teachers kept growing, eventually exceeding 80%, according to historical data from the National Center for Educational Statistics. Even today, 2 out of 3 high school and nearly 9 in 10 elementary school teachers are women.

Denying them kids of their own

What it means to be a good teacher has shifted over time, along with prevailing views on what constitutes moral behavior. Teachers’ employment contracts have always reflected these notions.

A Story County, Iowa, contract from 1905, for example, required all teachers to go to church every Sunday and “take an active part, particularly in choir and Sunday School work.” It forbade dancing, drinking booze, playing cards, smoking or “loitering” in ice cream parlors.

Some rules for those Iowa teachers varied by gender. The 1905 teachers contract specified how often male teachers could go “courting.” But it also warned that “women teachers who marry or engage in other unseemly conduct will be dismissed.”

This discrimination eased gradually, partly due to labor union demands. Starting in 1915, for instance, New York State allowed women to work as teachers after having children – but not while pregnant. Expectant teachers had to take unpaid leave, with no guarantee that their job would be awaiting them later on.

The Supreme Court eventually found that mandatory maternity leave for teachers violated the Constitution, in its 1974 Cleveland Board of Education v. LaFleur ruling– three years after Warren says she lost her teaching job for being pregnant. Congress passed a law that banned pregnancy discrimination in all lines of work four years later.

Redefining moral turpitude

Due to a combination of changes in state and federal laws, judicial rulings and labor organizing, teachers now have far more protections from arbitrary dismissal and unwanted public attention to their lives outside of the classroom.

For example, 46 states grant teachers tenure after one to five years of probationary teaching – meaning that they cannot be fired without just cause. Until then, they have few protections.

What’s more, tenure can be revoked based on grounds that vary by state. The reasons can go beyond incontrovertible rationales, such as incompetence or neglecting their duties. Even today, nearly all states have laws that permit the dismissal of a teacher for immorality, immoral character or moral turpitude. In turn, those rules affect the rights of teachers hired at the local level.

Because the authorities do not clearly define what constitutes immorality, teachers face inconsistent standards that are constantly changing. Legal cases involving teachers dismissed on moral grounds because of their sexual orientation make that clear.

In 1962, Thomas Sarac lost his teaching job after being arrested for making sexual advances to another man, in public, in Long Beach, California. A district court upheld his dismissal and the loss of his teaching credentials based on what it called “immoral and unprofessional conduct and evident unfitness for service.”

But in 1963, Marc Morrison, another California teacher, was fired for having had a sexual relationship with a man, in private, which led to a similar court case. California’s supreme court ruled in Morrison’s favor six years later, finding that a teacher’s “immoral behavior” must have a demonstrative impact on their “fitness to teach.”

In 1971, a student’s mother informed the principal of Cascade High School in Turner, Oregon, that biology teacher Peggy Burton was “a homosexual.” Burton didn’t deny it, so he fired her – and she became the first U.S. LGBTQ teacher to file a federal civil rights suit. A district court judge awarded her US$10,000 (the equivalent of $63,400 today), but Burton didn’t get her job back because she lacked tenure.

An Oregon law passed in 2007 now prevents such firings, but 28 states including Florida and Montana lack legal protections for LGBTQ employees.

Protecting sexual freedoms

Several other rulings protected sexual freedoms for teachers.

In 1974, a district court judge found that Frances Fisher, a divorced Nebraska teacher who lived alone, shouldn’t have been fired for having a man sleep in her apartment and ordered her job reinstated.

In 1976, another district court considered the firing of Joseph P. Sedule, a married Delaware school administrator, for reasons related to his affair with a woman who was also married to someone else. That ruling dismissed moral concerns about adultery and focused instead on Sedule’s workplace misconduct, finding the firing justified on that basis alone.

More recently, many court cases have tested the limits of teachers’ online sexual behavior, indicating that society still expects teachers to meet strict moral standards.

For example, the San Diego Unified School District fired middle school teacher Frank Lampedusa after he posted a graphic gay personal ad on Craigslist. A state appeals court upheld Lampedusa’s firing.

Meanwhile, LGBTQ teachers in Catholic schools can still lose their jobs on the grounds that they are violating immorality clauses in their contracts.

AP Photo/Matt Rourke

Lingering expectations

In his 1973 ruling on the landmark LGBTQ civil rights case brought by Oregon teacher Peggy Burton, Judge Gus Solomon observed that “immorality means different things to different people.”

He went on to question whether school board members should be the arbiters of a community’s moral standards, arguing that the “potential for arbitrary and discriminatory enforcement is inherent” in any official attempt to define moral codes.

Nearly half a century later, there are still no clear answers to questions about what teachers can or can’t do to meet society’s ethical ideals as role models for children.

[ You respect facts and expertise. So do The Conversation’s authors and editors. You can read us daily by subscribing to our newsletter. ]![]()

Kyle Greenwalt, Associate Professor, Michigan State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.