Trysh Travis, University of Florida

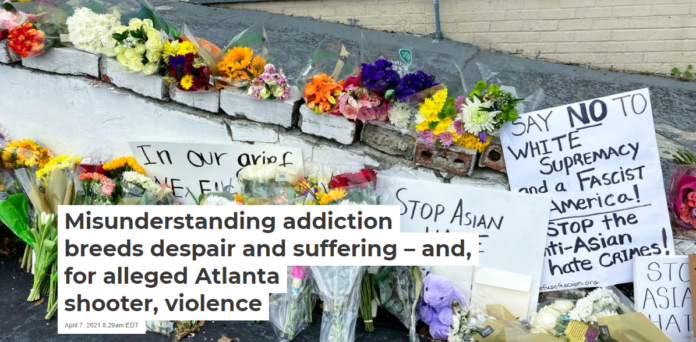

When a man claiming to suffer from the disease of sex addiction found that “comprehensive and fully integrated treatment” at a Christian recovery center could not cure him, he decided to try another approach: eliminating the women he believed were a “temptation” aggravating his problem.

That’s the best understanding so far of what drove Robert Aaron Long to allegedly murder eight women, including six of Asian descent, in Atlanta, Georgia on March 16, 2021.

To me as a cultural historian of addiction and recovery, his story highlights the two most common ways Americans think about and deal with compulsive behaviors. We like to consider them the results of temptation or treat them as diseases.

Although these two approaches are often treated as opposites, both stem from the most prominent effort to fight compulsion in U.S. history: the grassroots movement to ban alcohol, which led to national Prohibition from 1920 to 1933.

The disease concept of addiction arose in the aftermath of Prohibition, in part as a way to explain why the national alcohol ban didn’t actually get rid of alcohol or its abuse. Far from being a biomedical truth, it is just a way of framing compulsive drinking. The story of the alleged Atlanta shooter shows how well the disease concept succeeded as a public relations tool – and also how limited it is as a means of explaining human behavior.

A brief history of Prohibition

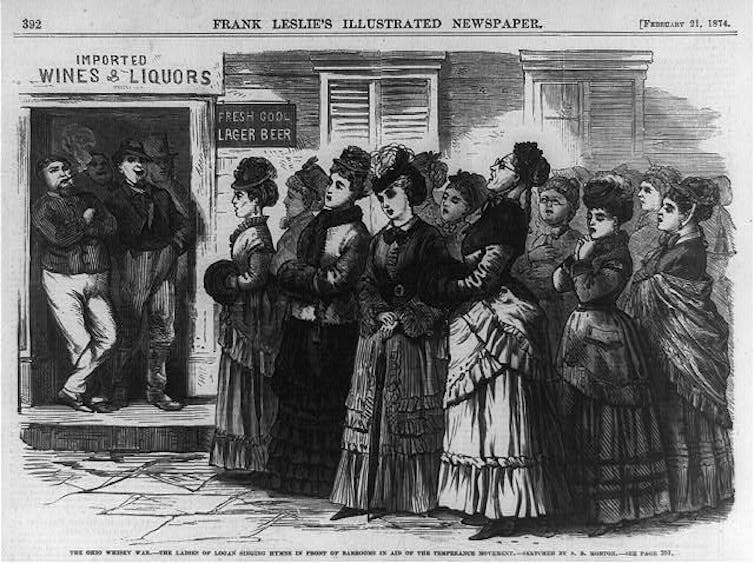

Beginning in the early 19th century, a broad cross-section of Americans – often led by women – looked at poverty, domestic violence, labor unrest and other social problems and connected them with drinking alcohol.

So-called “temperance” activists worked for years to limit alcohol consumption in the U.S. by promoting moderation and voluntary abstinence. “Prohibitionists,” by contrast, pushed to restrict the times and places liquor could be sold. Interrupted only briefly by the Civil War, both groups used moral suasion and political lobbying to shift the culture and the laws around alcohol.

Their tactics worked. Fraternal organizations promoted abstinence as a sound business principle; saloons were closed by prayer vigils; and many states enacted local provisions that allowed counties and municipalities to vote in bans or restrictions on liquor sales.

But by the early 20th century, “the liquor traffic” – the network of manufacturers and distributors, and the politicians who benefited from their kickbacks – seemed unstoppable. Around the nation, even in “dry” counties, “demon rum” flowed freely.

When men – problem drinkers were then, as now, disproportionately male – fell victim to its seductions, they abandoned their roles at home and in the workplace. This bad behavior threatened the social order.

In 1913, the Anti-Saloon League, which had previously championed the local option as a way to gradually reform the nation, had had enough. It was clear they could not shame or regulate the liquor traffic into limiting its hold on men’s lives. That left only one alternative, which had first been proposed two decades before by Archbishop John Ireland of St. Paul, Minnesota: “there is nothing now to be done but to wipe it out completely.”

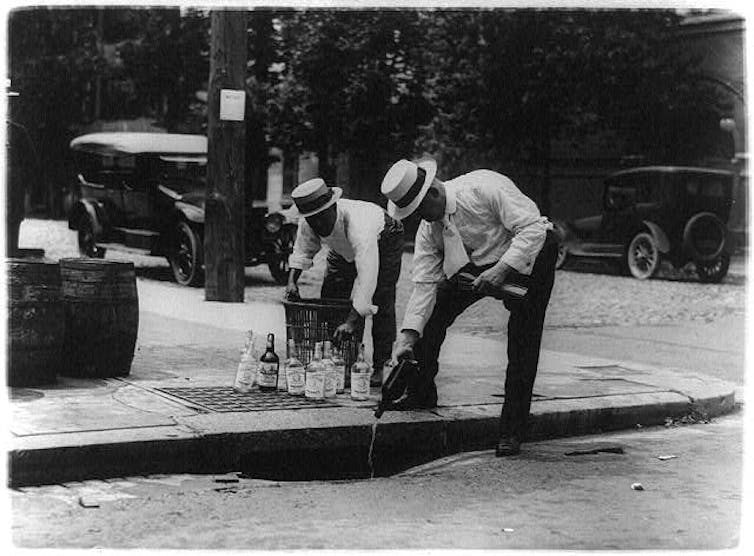

It took just six years for Congress to pass the 18th Amendment and for the states to ratify it, banning the production, transport and sale of intoxicating liquors. In January 1920, America was officially cleansed of “the great destroyer.”

A new understanding?

Even most Prohibition advocates quickly realized that alcohol could not really be wiped out of American life.

The nation also learned that the cost of trying was itself sky high. Illegal and bootleg spirits were more expensive – and often toxic. Instead of turning men into hardworking teetotalers, Prohibition encouraged new kinds of social deviance, such as organized crime.

When Prohibition was repealed in 1933, the liquor industry and its political patrons established and funded what historians call the “modern alcoholism movement.” This was a group of activist scientists, public relations experts and reformed drinkers looking to promote a responsible solutions to the problems of alcohol – while also keeping the booze flowing.

This movement acknowledged that some people were problem drinkers, but argued that neither the industry nor alcohol itself was to blame. Instead, during the 1940s and 1950s, movement members recast drunkenness as a personal and, significantly, a medical issue. They called it “the disease of alcoholism.”

This new disease was like an allergy. It was mysterious; it was not clear why some people developed a compulsion to drink. More important, it was rare: Most people could drink socially without ill effect. Those who could not deserved help, not scorn.

This medicalized approach claimed that with understanding and fellowship – such as that provided by Alcoholics Anonymous – disease sufferers could remain cheerfully abstinent. The scientific community would work to unlock the secrets of the disease of alcoholism, just as it had with tuberculosis and polio. In the meantime, the undiseased could enjoy the three-martini lunches and suburban cocktail parties that symbolized the postwar American good life.

Diseases spread

Billions of research dollars later, there is no clear consensus that the compulsive use of alcohol – or any other drug – is the effect or the cause of any physiological or genetic abnormality, or whether it is just bad decision-making.

But reframing problem drinking as a disease had helped everyone move on from the disastrous experiment of Prohibition. Alcoholics got sympathy, research scientists won government grants and the liquor industry made plenty of money marketing alcohol to Americans without the disease.

The disease concept was so useful to so many people that in the late 20th century, it migrated out of the alcohol and drug world. Overindulgence in anything – including work, exercise and sex – became known as “behavioral addiction.”

Near-total lack of evidence that such compulsive behavior has physiological roots has not stopped Americans from seeing it as disease.

The alleged Atlanta shooter fell into this trap. He was a man whose appetite for sex was larger than he thought it should be. His Christian community called that a sin. When he couldn’t pray his desires away, he appears to have borrowed a concept from the secular world and decided to treat it as a disease.

When that modern approach didn’t work, he took a step back in time, reverting to the old Prohibitionist tactic of eliminating what he believed to be the source of his problems.

The Anti-Saloon League used pressure tactics to change legislation. Robert Aaron Long got a gun and ended women’s lives.

[Like what you’ve read? Want more? Sign up for The Conversation’s daily newsletter.]

Trysh Travis, Associate Professor of Women’s Studies, University of Florida

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.