Jason Miller, Michigan State University

Most Americans may not appreciate the central role that private railroads play in supporting the U.S. economy and their everyday lives. Recent fears of a railroad strike may have changed that.

After 20 straight hours of negotiations, brokered by President Joe Biden, U.S. railroads on Sept. 15, 2022, reached a tentative agreement with their unions to avert a devastating strike that had the potential to grind freight rail activity to a halt, worsen already sky-high inflation and drive the economy into a recession.

The costs of a possible work stoppage were already becoming apparent, as some railroads stopped taking certain hazardous goods, such as fertilizer and chlorine destined for water purification plants. And Amtrak said it was canceling all long-distance trains – though the company said it was working to restore service following news of the deal.

The agreement, however, still needs to be approved by workers, and so a strike is still possible once the cooling off period ends in several weeks.

Given how close the U.S. economy was to a strike, the question remains: What would happen if railroad workers did walk off their jobs for an extended period?

I’ve been researching freight transportation operations in the United States for a decade and witnessed many major disruptions, from port strikes to natural disasters.

A prolonged railroad strike has the potential to be far more disruptive, affecting Americans across the country and imperiling the economy at a time when it’s already experiencing the twin threats of decades-high inflation and a Federal Reserve willing to slow growth to rein in the rising cost of living.

Why workers might strike

Rail workers have been without a contract since 2019, as management and unions have failed to agree on wage increases, paid sick leave and other issues.

On Aug. 16, 2022, a government panel drafted a compromise that included a 22% raise over six years and a cap on monthly health care contributions. Initially, 10 of the 12 rail unions tentatively agreed to the deal. But the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers and Trainmen and the International Association of Sheet Metal Air, Rail and Transportation Workers refused.

The key sticking points concerned working conditions, such as a lack of sick leave and policies that punish workers for taking unscheduled time off for a personal emergency.

The new deal, agreed to in the wee hours of Sept. 15, includes a 24% wage increase over five years effective retroactively to 2020 – meaning workers would get an immediate 14.1% bump. It would also allow workers to get time off for some medical events, which was a key issue for some unions.

The last time U.S. rail workers went on strike was in 1992. The strike lasted 24 hours before Congress intervened, which kept disruptions to a minimum.

Given the political paralysis in Washington, it’s uncertain whether lawmakers would be able to agree on a measure to resolve a strike in the current climate.

Why trains are so important

Railroads play a vital role in keeping the U.S. economy humming, transporting everything from convertibles and french fries to chemicals and coal.

Railroads are involved in 43% of all freight activity in the U.S., the Census Bureau estimates.

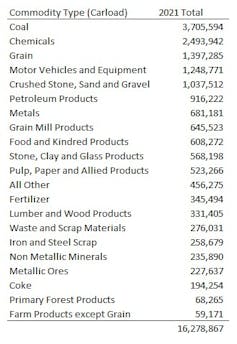

In 2021, for example, the major U.S. railroads hauled 16.3 million carloads of all sorts of raw goods, including coal, chemicals, lumber and grain. Placed end to end, the cars would require 187,800 miles of track – enough to circle the Earth’s equator over seven times.

Other than rail cars, the railroads also haul 1.2 million trailers for trucking companies and 15.6 million so-called intermodal containers – think the bright corrugated metal boxes that you have likely seen stacked up at ports and on massive ships. These containers are filled with imported products such as children’s toys, furniture and electronics, and goods produced domestically that need to be shipped a long distance.

Are there any other options?

However you count it, it’s clearly a lot of stuff. A natural question you might have is: Can’t semi trucks pick up some of the slack?

The answer is a resounding “no.”

Take just one product that trains ship – chemicals – which are used to make plastics, processed food, glass products and many other consumer goods. Recently, the five major railroads hauled an average of 47,900 carloads of chemicals a week. Each of these carloads has the capacity of four to five tanker trucks. So to make up for a shortfall, trucks would need over 200,000 spare tankers hauling stuff each week. There isn’t nearly enough capacity.

Even more problematic are the approximately 78,000 carloads of coal the railroads haul each week. Much of this coal is mined in Wyoming and must travel across the country to states like Texas, where it is used to generate electricity for industry and consumers.

There is no feasible way to transport this much coal in trucks.

The costs of a strike

And so the consequences of even a day or two of strikes could be significant – and a strike longer than that could become dire.

Coal, for example, is used to generate about 20% of electricity in the U.S. While utilities maintain roughly a 30-day stockpile of coal, the mines could not operate more than a few days before their limited storage capacity would force them to shut down. The effects for businesses and consumers could be substantial if these utilities needed to curtail power generation.

A halt would also likely worsen inflation by driving up energy costs.

The food supply is another area of concern. Each year, railroads transport over 3 million carloads or containers of agricultural products, from raw grains such as wheat and corn to finished goods like frozen meats and most other food products.

While some of these shipments could be switched to trucks, I estimate that at most they could cover 5% of what railroads transport based on commodity freight shipment data.

So the result would likely be more shortages and higher prices – bad news for consumers who have seen prices for groceries soar 13.5% from a year ago.

One other sector that would be severely disrupted are makers of cars and trucks, like Ford and General Motors. Auto plants rely extensively on railroads to deliver auto parts – not to mention they transport 75% of all finished vehicles.

A prolonged rail strike would therefore severely curtail auto assembly at a time when the sector is finally starting to dig its way out of assembly issues brought on by a chip shortage.

Finally, passenger trains like Amtrak and commuter rail have already been experiencing disruptions in terms of route cancellations, which would grow much worse if there are actual strikes. The reason is that many passenger trains operate on portions of freight railroads’ tracks. For example, about 70% of the miles that Amtrak trains log each year are on rails owned by the freight railroads.

Congress could intervene

All in all, a strike could severely harm the U.S. economy and drive up inflation. The Association of American Railroads estimated a strike could cost the economy US$2 billion a day.

If there are strikes – which remains a possibility if some railroad workers don’t agree to the new deal – Congress could intervene, as it did in 1992, to impose an agreement on workers. It’s the only solution beyond the negotiating table, thanks to the Railway Labor Act of 1926, which otherwise requires rail workers and management to negotiate their differences.

Fortunately, the two parties – with the help of the Biden administration – were able to reach a deal. Given the consequences, I hope it sticks.

This article was updated on Sept. 15, 2022, to include a new tentative agreement made between unions and railroads.

Jason Miller, Associate Professor of Supply Chain Management, Michigan State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.