Adrian V. Hernandez, University of Connecticut and C. Michael White, University of Connecticut

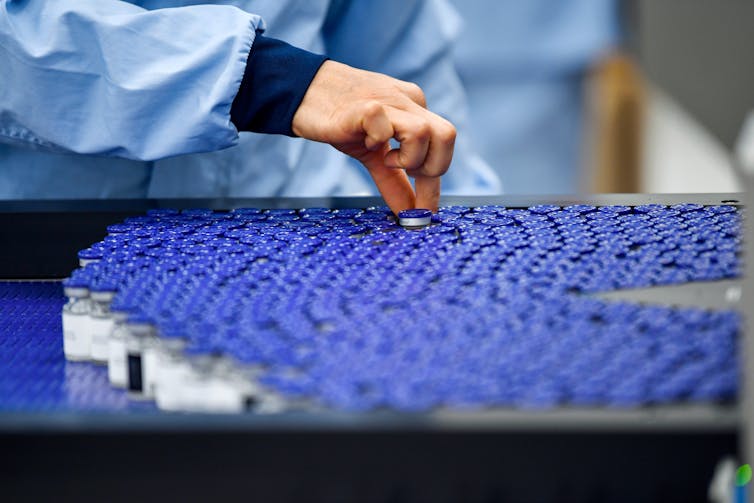

The latest setback for Johnson & Johnson’s COVID-19 vaccine was the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s order on June 11, 2021, to discard 60 million doses that failed to meet quality and safety guidelines. A Baltimore manufacturing facility run by Emergent BioSolutions had been producing COVID-19 vaccines for both J&J and AstraZeneca and inadvertently mixed up ingredients from the two companies.

The FDA regularly inspects manufacturing facilities to ensure that drugs meet rigorous quality standards. These standards are vital to protect patients from drugs that are incorrectly dosed, contaminated or ineffective.

But over the past few years, tens of millions of doses of prescription and over-the-counter drugs have failed FDA quality expectations. This includes the ongoing 2018 recall of thousands of batches of popular blood pressure, diabetes and acid reflux medications containing the probable carcinogen NDMA.

For perspective, the number of individual tablets and capsules for prescription and over-the-counter drugs entering the U.S. each year is counted in the trillions.

Manufacturers may still backslide while the pandemic continues to put inspections on the back burner. As a pharmacist and physician team investigating drug, device and dietary supplement safety, we are concerned about the current level of manufacturing oversight in the U.S. and overseas. To protect consumers, the FDA needs to strike a balance between quickly getting lifesaving drugs out to market and rigorously ensuring their safety.

FDA’s overseas oversight fell under the radar

Over the past 30 years, U.S. pharmaceutical companies have laid off tens of thousands of U.S. manufacturing workers and moved their drug manufacturing overseas. The main reasons for this outsourcing include cheaper labor, looser environmental regulations and less oversight. Meanwhile, pharmaceutical companies in India and China captured a greater share of the U.S. generic drug market. As of May 2020, 74% of facilities manufacturing active ingredients and 54% manufacturing finished drugs for the U.S. were located overseas.

Until 2007, the FDA focused almost entirely on inspecting U.S.-based manufacturing plants for drug quality. Foreign plants, on the other hand, were on the honor system: The FDA trusted their own internally generated paperwork as proof of compliance.

The folly of this system came to light in 2004, when a whistleblower alerted the FDA that Ranbaxy Corp., one of the largest generic drug companies in the world, was fabricating its drug test reports. Ranbaxy ultimately paid a US$500 million fine in 2013 for knowingly producing substandard drugs for the U.S. market since their first FDA approval in 1998.

The drug inspection overhaul of 2007 to 2019

After the Ranbaxy fiasco, the FDA increased foreign manufacturing inspections from 333 in 2007 to 966 in 2019. The proportion of foreign manufacturing plants that had never had an FDA inspection shrank from 64% in 2010 to 16% in 2019. Of those, the FDA also found that 37% did not need inspection because they either went out of business, were no longer supplying drugs to the U.S. or were not selling drugs to the U.S. in the first place.

As inspections increased, so did the number of serious drug safety issues that came to light. Dozens of Indian manufacturing facilities were barred from shipping drugs to the U.S. after the FDA discovered they were manipulating and omitting quality test results and had unsanitary production conditions. Similar findings resulted from inspections of Chinese manufacturing facilities, including the company behind numerous blood pressure drug recalls in 2019.

Decreasing oversight at US manufacturing facilities

One reason the FDA had less oversight of overseas facilities was limited funding. Before the 2012 Generic Drug User Fee Amendment, the FDA was primarily funded by user fees from pharmaceutical, vaccine and medical device manufacturers. The amendment imposed a $15,000 surcharge on each foreign manufacturing facility to cover the added expense of conducting on-site inspections overseas.

Despite increased inspection funding, the FDA remained stymied by an inability to fill job vacancies for both U.S.- and overseas-based inspectors. These vacancies are especially prevalent in India and China, where 33% and 30% of available overseas-based inspector jobs respectively remained unfilled as of most recent data available November 2019.

The 2012 FDA Safety and Innovation Act removed the legal requirement to inspect U.S. manufacturing facilities every two years. This was partly so the FDA could shift its domestic workforce to foreign inspections, and ensure that all facilities worldwide met the same target criteria. Domestic inspections subsequently decreased from 1,122 in 2007 to just 698 in 2019. Currently, the FDA inspects foreign and domestic manufacturing facilities every five years, or more frequently when serious issues are identified.

While the decrease in domestic inspections may have given the FDA more bandwidth for foreign oversight, this may have also pressured FDA officials to gloss over quality issues.

For example, the U.S. Office of Special Counsel discovered in March 2021 that FDA administrators had downplayed whistleblower concerns about serious quality issues in U.S. vaccine manufacturing facilities from 2017 to 2018.

Similarly, a 2020 FDA inspection had already identified numerous facility and manufacturing issues in Emergent BioSolution’s Baltimore facility. Had these findings been immediately addressed, cross-contamination with the Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine would have been less likely. But none of these issues was deemed serious enough to halt production. They were instead allowed to be gradually resolved as production continued.

How has COVID-19 affected foreign inspections?

The gap between foreign and domestic inspections has widened over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic. Because international travel shut down after March 2020, the FDA conducted only three overseas inspections, and 52 in the U.S.

The effects of the pandemic on inspections may be long-lasting. As of 2020, 13% of foreign manufacturers have never had an inspection since doing business with the U.S. Another 17% have not been inspected for over five years. With current staffing levels, it will likely take a long time to remedy the backlog.

What does it all mean for consumers?

Until the FDA has sufficient personnel to conduct rigorous on-site inspections, consumers don’t have many options. Because many states allow or mandate automatic substitution of products the FDA deems bioequivalent, consumers have limited ability to specify which manufacturer’s version they would like to receive at the pharmacy counter.

U.S. consumers can have much more confidence that the drug products they receive today are of higher quality than those from the early 2000s. But the loss of tens of millions of COVID-19 vaccine doses due to poor manufacturing oversight underscores the value of prospective inspections and the risks that reducing domestic inspections pose.

[Research into coronavirus and other news from science Subscribe to The Conversation’s new science newsletter.]

Adrian V. Hernandez, Associate Professor of Comparative Effectiveness and Outcomes Research, University of Connecticut and C. Michael White, Distinguished Professor and Head of the Department of Pharmacy Practice, University of Connecticut

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.