Melissa M. Jozwiak, Texas A&M-San Antonio and Carl Sheperis, Texas A&M-San Antonio

The American Families Plan, announced by President Joe Biden in April 2021, aims to make child care more affordable for parents. Importantly, it also seeks to ensure caregivers are paid a living wage – enough to meet basic needs given the local cost of living. If passed, all workers in child care and pre-K programs that receive federal subsidies would earn at least US$15 per hour. Preschool teachers and child care workers with similar qualifications as kindergarten teachers would be paid in line with what kindergarten teachers earn.

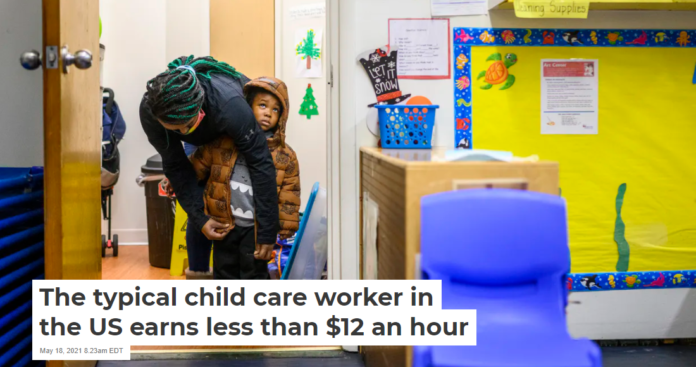

Currently, child care workers who care for infants and toddlers tend to earn much less than those who care for older children.

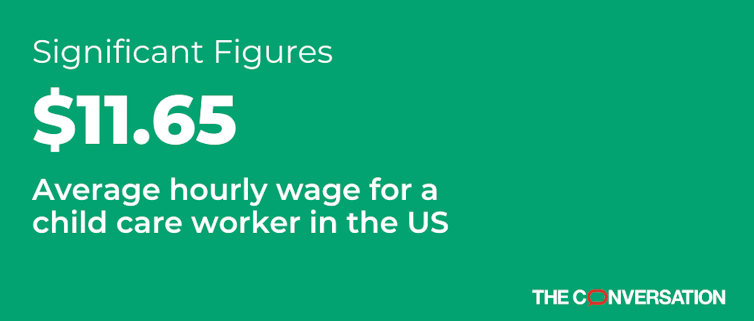

In 2019, child care workers across the United States earned an average wage of $11.65 per hour. That includes people who worked in child care centers and schools as well as private homes. As a result, in several states, over 25% of those workers – overwhelmingly women – live at or below the poverty level.

Although early childhood caregivers saw a slight increase in wages in 2020, to $12.88 per hour, it was a temporary bump due to some being classified as essential workers or receiving hazard pay during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The median annual income for a child care worker is about $25,500 for 12 months of work, compared to a preschool teacher’s median salary of just under $32,000 for, often, 10 months. A kindergarten teacher, meanwhile, earns roughly $58,000, typically for 10 months.

Critical development years

As experts in child development and infant and toddler mental health, we know how important high-quality care is for a child’s development.

A child’s brain develops rapidly from ages 0-5 when the foundational structures for learning and human interaction are established. Research shows that sensitive and stimulating caregiving, where materials and experiences are carefully selected to engage a child’s senses, set off a series of connections between neurons in their brain.

A caregiver helps a child thrive by providing consistent attention, back-and-forth communication and emotional responsiveness – during routine times of diapering and feeding, as well as during planned activities.

Failure to respond or responses that are provided by a primary caregiver experiencing higher levels of anxiety have been shown to have an impact on the way the child’s brain develops.

Impact of low wages

According to the Center for the Study of Child Care at University of California Berkeley, caregivers in only 10 states are paid what’s considered a living wage. As a result, nearly half of this workforce nationwide depends on public income support programs like food stamps or Medicaid.

The salary inequities can’t be explained away by lower levels of academic training or easier workdays. Early childhood educators with bachelor’s degrees earn as little as half of what K-8 teachers with the same credentials earn.

And whether caregivers are sitting on the floor playing with a child or lifting them into highchairs, the job is physically demanding – especially in states like Florida and Texas where one caregiver may be responsible for 10 or more toddlers. Plus, the average toddler weighs over 25 pounds.

Low wages, few benefits, stressful work conditions and feeling like their work isn’t valued are factors affecting the high turnover rates and staffing shortage in child care.

A shortage of qualified staff hurts employers, but it also affects the young children who depend on them for care. Continuously changing caregivers influences quality of interaction and attachment. During such a critical period of growth in a child’s life, when development depends on the caregiver’s attention to a child, we believe caregivers should be paid a wage that makes it possible for them to afford health care – including mental health services, should they be needed – and minimizes distraction from worries about their own economic stability.

[Like what you’ve read? Want more? Sign up for The Conversation’s daily newsletter.]

Melissa M. Jozwiak, Associate Professor of Early Childhood, Texas A&M-San Antonio and Carl Sheperis, Professor of Mental Health Counseling, Texas A&M-San Antonio

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.