Wesley Widmaier, Griffith University

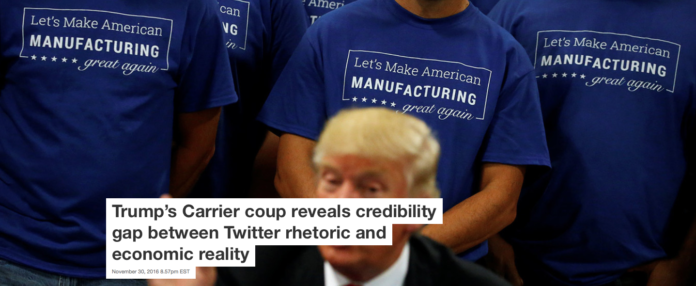

In a political coup, President-elect Donald Trump says that his transition team has struck a deal with Carrier’s Indianapolis plant to keep 1,000 jobs in the state.

Big day on Thursday for Indiana and the great workers of that wonderful state.We will keep our companies and jobs in the U.S. Thanks Carrier

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) November 30, 2016

This builds on Trump’s recent tweets directed at the air-conditioner maker and Ford, as he sought to deliver on a campaign promise and reverse what his populist predecessor Ross Perot termed a NAFTA-spawned “giant sucking sound” of jobs leaving the Rust Belt.

To some degree, Carrier’s retreat may reflect its own concern for public opinion. Reports also suggest that Trump wielded sticks and carrots. Carrier depends on the government for approximately US$5.6 billion in military sales – a figure that dwarfs the $65 million in savings from moving the Indianapolis plant to Mexico, and executives may have had some fears of retaliation. Trump also could offer inducements – in the form of state tax breaks (as Vice President-elect Mike Pence is still the governor of Indiana) and pledges of an easier line on potential tax and tariff policies.

Yet, while likely to result in praise, these moves raise a number of questions. How legitimate is presidential “jawboning” of businesses? When are such measures effective in containing market abuses or achieving legitimate broader economic ends – as opposed to ineffective acts of political theater? When do they represent abuses of political power or authority? And what are the implications for the Trump administration’s broader economic policy?

Trump wouldn’t be the first occupant of the White House to try to bend individual companies to his will. Fortunately, economic history – and specifically an incident in 1962 I recount in a just-released book – offers some insights into these questions and their implications if this is to be Trump’s style going forward.

AP Photo

JFK squares off against US steel

Speaking to the issue of legitimacy, one might ask whether Trump’s stance represents a new power grab or a revival of a forgotten tradition.

In fact, there exists a long tradition marked by the use of presidential rhetoric to highlight public or “macro” interests in ostensibly private or “micro” corporate choices. Over the past century, such public interests have found expression across Theodore Roosevelt’s appeals for rail price controls, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s support for New Deal-era price codes and World War II-era “General Max” price guidelines.

This view reached its peak in the 1960s when President John F. Kennedy urged Americans to “ask not what your country can do for you – ask what you can do for your country.” This exhortation voiced a then-prevailing sentiment that a common good existed, one that “trumped” individual choices.

To advance such macro interests, presidents accordingly engaged in “jawboning” of labor and business leaders. For example, they often stressed their shared interests in wage-price restraint, and issued threats to both companies and unions, lest wages chase prices in an inflationary spiral that produced no real gains for anyone.

Perhaps the most famous such initiative revolved around a 1962 struggle between Kennedy and major steel producers. Given fears that steel price increases might spark renewed inflation, Kennedy put pressure on the steel companies, arguing – as one adviser put it – that “if you play ball on this, I’ll help get labor into a more receptive mood on a reasonable settlement in 1962.”

Indeed, Kennedy would deliver, as unions swore off wage increases. When steel negotiations concluded on March 31, 1962, the United Steelworkers union agreed to no wage hike, accepting only a 2.5 percent increase in fringe benefits.

Yet, peace would not last. As I recount in my book “Economic Ideas in Political Time,” U.S. Steel President Roger Blough visited the White House less than two weeks later to inform Kennedy that his company would hike steel prices by 3.5 percent. Kennedy exploded, accusing Blough of deceiving him.

The administration more broadly responded on a number of fronts, deploying antitrust threats, diverting contracts and most importantly using presidential rhetoric. Kennedy publicly condemned “a tiny handful of steel executives whose pursuit of private power and profit exceeds their sense of public responsibility” and noted that the identical price moves of large steel firms wasn’t “the way we expect the competitive private enterprise system to always work.”

Given national outrage, the steel companies rescinded the increase within days. Kennedy had won.

So does it work?

How effective are such measures over time?

One thing worth noting is that such measures must be part of a sustained effort to promote self-reinforcing expectations. If people think they will work, they will work. If people think they will fail, they will fail. The political context matters.

In this light, it should be emphasized that after the steel confrontation, business more broadly moved to oppose Kennedy, suggesting that his measures posed threats to economic efficiency and political liberties. Chamber of Commerce President Richard Wagner noted, following the confrontation, that “dictators in other lands usually come to power under accepted constitutional procedures.”

While Kennedy was initially able to use his bully pulpit to get businesses to toe the line, steel companies eventually became adept at playing the expectations game. They would often announce excessive price increases and then quickly accept sham “compromises.” Or they would simply stagger announcements of price hikes or job cuts, revealing them in dribs and drabs or waiting until the holidays when even presidential denunciations might go unheard.

In terms of economic criticisms, free market economist Milton Friedman denounced Kennedy’s “fundamentally subversive doctrine,” noting that the steel crisis had demonstrated “how much of the power needed for a police state was already available.” Rather than highlight the notion of a uniquely public interest, Friedman warned that the steel crisis had shown that “if the price of steel is a public decision, as the doctrine of social responsibility declares, then it cannot be permitted to be made privately.”

In this way, at the height of the Keynesian era, one can see the reaction against appeals to limit private abuses of the public good that foreshadowed today’s neoliberalism, which sees private choices as largely equating with the public good. Friedman’s counterargument marked the acceleration of a shift to a belief that – as Margaret Thatcher put it – “there is no such thing as society,” but only “individual men and women.” Expressing a classically liberal suspicion of public power, Ronald Reagan put it best in 1981 when he said that “government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem.”

What it means for Trump

These historical parallels therefore offer grounds for a skeptical view of the efficacy of Trump’s exhortation – and highlight the possible difficulties a Trump administration might find as it pursues Carrier-styled interventions.

First, Trump’s ideology – if not the wider culture – is marked less by a Keynesian-Kennedy commitment to regulation in the “macro” interest than to a Friedman-Reagan styled aversion to regulations that distort “private” choices. This increases the difficulty for Trump of enabling any self-reinforcing shift in business attitudes away from cost-cutting and in support of higher wages – even if this were his goal. And it’s more likely to encourage other companies to threaten to move employees in order to get more benefits – even if they have no intention of leaving.

Moreover, even if Trump’s sentiments had not been in accord with a neoliberal stress on liberating private choices, he would face opposition from a Republican Congress in any effort at reshaping business attitudes. House Speaker Paul Ryan has himself stressed the need to deregulate industry further.

Theoretically, Trump’s rhetoric might be married to a policy agenda like that of Bernie Sanders – who has proposed an “Outsourcing Prevention Act” to limit access to federal contracts, tax benefits, and grants or loans to companies found to have been engaged in outsourcing.

Given these tensions, Trump’s act in saving the Carrier jobs might foreshadow a revived Keynesian stress on raising wages – or be revealed as a rhetorical diversion that obscures a reinforced neoliberal stress on profits.

If Trump is serious about working class concerns, he must offer appeals that go beyond tweets and promote regulatory initiatives resistant to corporate “gaming.” Put differently, as impressive as this early rhetorical success may be, observers should wait to see how it accords with Trump’s policy “reality.”

![]()

Wesley Widmaier, Australian Research Council Future Fellow, Griffith University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.