Paul D. Larson, University of Manitoba

Cut flowers are a multi-billion-dollar business globally, closely linked to social events and holidays, such as Christmas, Hanukkah and Mother’s Day, and to happy and sad occasions, like weddings and funerals.

And then there’s Valentine’s Day.

In the United States alone, an estimated $1.9 billion worth of cut flowers are sold on or before Valentine’s Day each year. As Valentine’s Day approaches, and the chill of winter lingers, it leaves one wondering: Where do all these flowers come from? How do those roses get from grower’s land to lover’s hand?

As a professor who studies sustainability, I’ve investigated the impact of many business models, including cut flowers. If there’s enough money to be made (or favour to be won), the social and environmental implications of business decisions often are trumped by short-term economics.

The flower industry

Since 2019, the worldwide cut flower market had been blooming. The market for cut flowers, houseplants and landscape greenery was expected to grow roughly 6.3 per cent over the five years ending in 2024.

But that market wilted to an estimated US$29.2 billion in 2020, a 6.2 per cent contraction from 2019, largely due to the pandemic. In top spot, the United States accounted for US$7.9 billion, or 27 percent of the 2020 global market.

Florists typically sell cut flowers, as well as floral arrangements and potted plants. These items come from both domestic and foreign flower farms and wholesalers. In the U.S. and Canada around 80 per cent of these flowers are imported.

Florists are small businesses. In both Canada and the United States, the average florist has only about two employees. In Canada, the florist industry consists of an estimated 2,822 retail businesses, 5,054 employees and annual sales revenue of $602 million. In the U.S. last year, there were 31,663 florists, with 65,000 employees, in a US$5 billion market.

The cut flower supply chain

The cut flower supply chain often starts in Colombia. About 80 per cent of cut flowers sold in the U.S. are imported. Colombia is the No. 1 country of origin and Ecuador is No. 2.

While the Netherlands produces 80 percent of the world’s tulips, Colombia and Ecuador are the world’s largest producers of carnations and roses, respectively. As a symbol of love and romance, roses are the world’s most popular flowers.

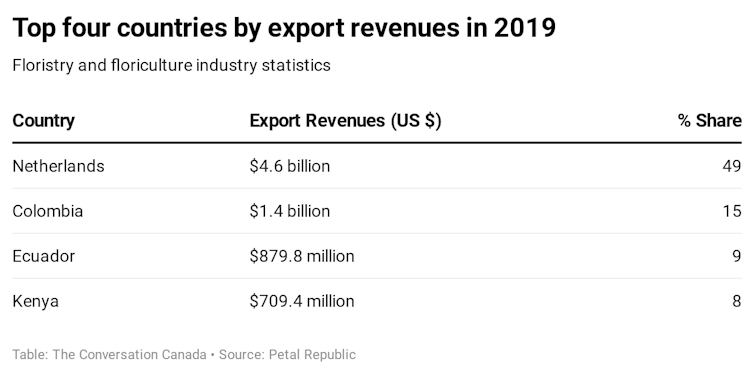

The top four flower producing countries in 2019, in terms of export revenues, were: The Netherlands ($4.6 billion), Colombia ($1.4 billion), Ecuador ($879.8 million) and Kenya ($709.4 million).

Flowers grown on the Bogotá Plateau are cut, combined into bundles and hydrated for up to 24 hours — in preparation to enter the “cold chain.” As roses travel to Bogotá’s El Dorado International Airport in refrigerated trucks, shipping and storage temperatures are maintained at about 1C.

Next, those roses are flown to Miami, Fla. In fact, most cut flowers destined for the U.S. or Canada arrive via Miami International Airport.

In the case of Edmonton-based Grower Direct, roses and other cut flowers are loaded onto refrigerated trucks for direct delivery to stores across Canada. The entire journey, from farm to flower shop, takes as little as four days. Despite the speedy journey, 45 per cent of all cut flowers die before they are sold.

Low wages, pesticides and greenhouse gases

Sustainability attempts to balance social, environmental and economic implications of decisions and actions, today and into the future.

While the cut flower industry provides jobs for producers and distributors, there is a price. The International Labor Rights Fund notes that the industry has a reputation for low wages and poor working conditions. Workers on Colombian flower farms are predominantly female. They work 16 or more hours a day for a monthly wage of about $300.

Since flowers are not classified as edible, they are often exempt from pesticide regulations. Thus, many flower production workers in Ecuador and Colombia have suffered from respiratory problems, rashes and eye infections caused by exposure to toxic chemicals in fertilizers, fungicides and pesticides.

The Fairtrade movement is a response to this mistreatment. It aims to improve working conditions for flower farmers and workers, as well as living conditions in their communities, by ensuring they earn a living wage and by protecting their rights.

Moving flowers from South America to North America, in refrigerated trucks and cargo planes, in and out of warehouses along the cold chain, yields a large carbon footprint. During a typical peak season, 30-35 cargo planes arrive in Miami from Bogotá every day to meet American demand. While local production would ground some of those flights, growing flowers in greenhouses can use as much energy as shipping them from Colombia by air freight.

COVID-19 impact

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a “global pandemic.” The timing could hardly have been worse for the cut flower industry.

Spring is the industry’s busy season, with weddings, Easter and Mother’s Day. But soon, weddings were being postponed and flower shops closed. As lockdowns went into place around the world, the market wilted. Growers in Kenya and Colombia began to toss roses away.

Now, as lockdowns and other restrictions begin to ease up, there is optimism that 2021 will be better, starting with Valentine’s Day. Indeed, the Society of American Florists anticipates “the biggest Valentine’s Day in decades” in 2021.

But what if you forget to bring a bouquet of roses to your Valentine on Sunday? You could remind him or her or them about the social and/or environmental ills of the cut flower industry.

Or, you could just buy the damn flowers. But be sure they are Fairtrade certified or locally grown. And be sure to wear a mask.

Paul D. Larson, CN Professor of Supply Chain Management, University of Manitoba

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.