Peter Stearns, George Mason University

The word “shameless” is being tossed around an awful lot these days, which might speak to what many see as the country’s increasingly coarse, vitriolic political discourse. Perhaps, the thinking goes, American culture could use a dose of shame and humility.

But what about people harassed on social media, like Walter Palmer, the dentist who hunted and killed Cecil the lion? Sure, he might have exercised poor judgment. But was it poor enough that he deserved to have his wife and daughter not only shamed but threatened?

As I point out in my recent book “Shame: A Brief History,” the use of shame in American society has a clear historical arc.

But the role played by this emotion – which people feel when they’ve violated group standards – has also been complicated by several recent changes to the country’s legal, political and media ecosystems.

These shifts raise questions about how this powerful but unpleasant emotion should be handled in contemporary America.

A new, ‘enlightened’ direction

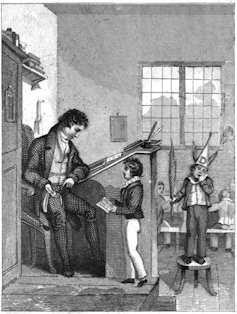

Western societies, including the American colonies, once relied heavily on shame. There was a deep belief in the importance of conformity to community stability. There was also a dearth of other resources we rely on today – such as policing – to enforce order.

ermess

Colonial Americans felt little compunction in imposing shame-based punishments like public stocks, whose replicas now amuse camera-toting tourists in New England. There was even a word no longer in use – “shamefast” – that described people who were mindful about avoiding shameful situations.

All this began to change in the late-18th century, when the currents of the Enlightenment started to spread throughout Western culture, and public leaders began to reevaluate the importance of human dignity.

Shaming, Founding Father Benjamin Rush wrote in 1787, “is universally acknowledged to be a worse punishment than death.”

Hyperbole aside, the actions of Americans started to reflect this new wisdom. Public stocks began to be abolished by law, beginning with Massachusetts in 1804. Parents were advised to avoid shaming their kids, lest it damage their confidence. (The popular use of the word “self-esteem” traces back to as early as 1856.)

Wikimedia Commons

Of course shame didn’t disappear; various people in positions of authority continued to deploy it, from boot camp drill sergeants to coaches of sports teams. Nonetheless, disapproval of shame-inducing tactics persisted. Schools gradually cleared out the most blatant practices (dunce caps, for example, were abandoned by the 1920s). All sorts of groups urged that people no longer be shamed for their sexual proclivities or their disabilities. A greater tolerance emerged that left people freer to accept treatment for psychological problems or to disclose their sexual identity.

In recent decades, psychology research has found that feelings of shame can demoralize people or generate aggression because they make individuals feel bad about themselves. (This differentiates shame from guilt, which, because it focuses on a person’s acts rather than his or her character, can lead to apology and redress.)

Today, public scholars like social work researcher Brené Brown continue to talk about these findings, urging those suffering from shame to throw the emotion aside and call their accusers to account – shaming the shamers, as it were.

Shame’s revival

The critical view of shaming in Western culture is now entrenched: While the behavior persists, it’s often condemned, and a variety of institutional changes, from grade inflation to prison reform efforts, limit its impact.

And this continues to change our society in important ways, loosening a number of traditional constraints that, if violated, used to lead to public shaming. Unmarried middle-class women can now proudly bear children, while public listing of school grades is outlawed.

Recently, however, attitudes toward shaming have shifted, even as the chorus of disapproval continues. According to a Google Ngram search, references to shame in written texts – in decline in the United States since the mid-19th century – have, in recent decades, increased far more than in other English-speaking countries.

The result, at least implicitly, is a new debate, and another divide in American culture.

By my reading, three sources account for the change. First, a number of conservative judges in the 1960s ruled that shaming was an appropriate punishment for certain crimes like drunken driving or petty theft. The stocks haven’t been reintroduced and many higher courts have disputed the new enthusiasm, but many criminals have been required to put shaming signs in their cars or to stand in a mall with a sign proclaiming their wrongdoing.

Second, the notorious culture wars in the United States have produced partisan camps eager to shame their opponents. Even liberals, probably hostile to shaming in principle, join the parade, as in the ubiquitous (and so far abortive) efforts to shame our current president and his supporters.

Third, social media have unleashed a torrent of hatred, with fat-shaming and accusations of sexual impropriety, hypocrisy and racism flooding social networks. The efforts can hound victims out of their jobs, force them to relocate – even drive some to suicide.

Shame at a crossroads

These shifts have created a dilemma: Are we shaming enough, or too much?

Some observers, whether they’re concerned about loose sexual behavior or the greed of global capitalists (one of whom proclaimed that “shame is for sissies”), can make a good case for a more robust restoration of community shaming.

It might not mean returning to stocks and dunce caps, but society could do a better job defining what deserves to be shamed, while also setting limits. As American community life has atrophied, this ability seems to have weakened. We certainly seem to have lost the knack – available in more shame-based societies – of helping people recover from shame and become reintegrated into the community.

But what about protecting people against being forced to adhere to an unpleasant level of conformity? What about the cruelty and harshness of social media shaming, in which a misguided comment or mistake can end a career?

![]() Admittedly, the unruly contemporary history of American shame more readily suggests problems than solutions. The country has lost both the comfortable reliance on shame of its colonial ancestors and the confident resistance to it of humanitarian reformers.

Admittedly, the unruly contemporary history of American shame more readily suggests problems than solutions. The country has lost both the comfortable reliance on shame of its colonial ancestors and the confident resistance to it of humanitarian reformers.

Peter Stearns, University Professor of History, Provost Emeritus, George Mason University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.