Christopher T. Conner, University of Missouri-Columbia

When coronavirus restrictions threatened the White Party, an annual circuit party held in Palm Springs, California, the organizer, Jeffrey Sanger, decided to move the festivities to Jalisco, Mexico.

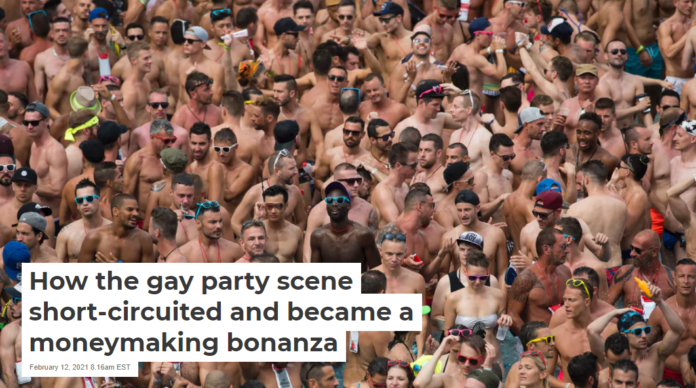

Gay partygoers from around the world descended on the small coastal state for the New Year’s Eve bash. Stars from Ru Paul’s Drag race made appearances, and even some doctors and nurses, fresh off their first COVID-19 vaccine doses, got in on the action.

The social media backlash was swift. Mexico, at that time, had one of the highest mortality rates – measured as deaths to cases – in the world. Others pointed out that the influx of tourists could strain existing hospital resources. Above all, the partygoers seemed to embody the arrogance, privilege and excess of people who prioritized a good time over a global health emergency.

While other gay events have also been occurring during the pandemic, this one particular party seemed to strike a nerve within the gay community.

For five years, my colleagues and I have been attending these circuit parties to interview attendees. We’ve sought to better understand the positive ways these parties influence gay culture, along with some of the problems they can present.

To me, Sanker’s decadent bash – held in the throes of the coronavirus pandemic – epitomized a growing divide in gay culture.

On one side, there are those who continue to push the political boundaries and, in so doing, embrace the legacy of community-building that emerged from the post-Stonewall era of LGBTQ activism; on the other, a group which seems to reject any notions of solidarity nor express any desire to know more about the history and political implications of their actions.

Early parties center on solidarity

The circuit party emerged in the late 1980s and came out of the underground gay club scene established by Black and Latino men living in Chicago and Detroit.

The name “circuit” was affixed to a particular branch of electronic dance music party due to the style of house music, dubbed “circuit house,” that played almost exclusively at these gatherings. Early circuit house enthusiasts subscribed to the values of P.L.U.M. – Peace, Love, Unity and Movement – though the “M” would later be replaced with an “R” for “Respect.”

The circuit soon came to simply refer to the network of underground nightclubs where gay men could dance together. These spaces also fostered solidarity among gay people, helping them feel less stigmatized and normalizing some of the issues they faced, whether it was HIV/AIDS or rejection by family and peers.

As one 45-year-old gay male man told me, these early parties were “small, intimate affairs. We were all looking for a way to connect with each other, and we didn’t have many options, so the circuit became a space for us to belong and a place where we could be free.”

The circuit becomes expensive and exclusive

For LGBTQ people, this quest for belonging hasn’t gone away.

A 2013 Pew survey reported that LGBTQ people still felt high rates of discrimination exclusion from traditional institutions such as the family, church and the workplace. A 2019 survey of LGBTQ Southerners found that participants felt an attachment to LGBTQ cultural spaces like gay bars and neighborhoods. For all the progress that has been made, these enclaves remain some of the only spaces in society where gayness is the norm.

Broader civil rights gains have coincided with technological advancements, with the internet and social media dramatically changing human interaction and collective organizing. A whirlwind of dizzying social change driven by likes, views and shares has led to greater feelings of what sociologists call “anomie” – a French word used to describe feelings of disconnectedness and a lack of community.

Circuit parties are not immune to this change. No longer do individuals attend the circuit to make a political statement; instead, the culture of the circuit seems to be focused almost exclusively on celebrating and seeking hyper-masculine and heteronormative standards of beauty.

For partygoers, this often means building a muscular frame, having risky sex and using drugs. They’ll also engage in what’s been described by other academics as “body fascism” – the exclusion and policing of how partygoers are supposed to look. This cut, masculine ideal is also reflected in ads for the events.

Today, circuit parties have become large-scale international productions costing hundreds of thousands of dollars, leading to an increase in ticket and travel costs. This has made the events more exclusive and also less racially diverse, since men of color tend to have less disposable income to attend these events and can also be the target of racial slurs and second-class treatment.

“This is no longer a political event,” one 50-year-old male party promoter told me. “This is a music festival, and we have to make as much money as possible.”

When subcultures get co-opted by capital

One of the greatest strengths of the gay rights movement has been its ability to combine activism with fun. However, as my research shows, unless there’s an intent to prioritize political agendas, group solidarity can easily be eroded.

Sanker has noted that as his events have become more profitable, they’ve faced less opposition from public officials and conservative groups.

But this profitability has meant scrubbing controversial political messages from the events to make them as palatable to as many customers as possible.

Something, clearly, has been lost.

Sociologists are keen to note how cultures – along with subcultures – often emerge as a way to alleviate feelings of isolation and suffering.

However, cultural events often become co-opted by profit motives. When this happens, they become less about caring for one another, building a sense of community or celebrating the positive aspects of humanity.

Instead, with pure profitability and escapism front and center at the White Party, it’s no wonder that the health of the attendees – along with that of the locals – was shrugged off.

[Insight, in your inbox each day. You can get it with The Conversation’s email newsletter.]

Christopher T. Conner, Visiting Assistant Professor of Sociology, University of Missouri-Columbia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.