Marianne Hanson, The University of Queensland

A flawed nuclear weapons treaty has finally come unstuck at the United Nations.

For decades, non-nuclear armed states have been asking the nuclear armed states (primarily the US, Russia, Britain, France and China – referred to as the NPT-P5 – but also India, Pakistan, Israel and North Korea) to fulfill the promises they have made to eliminate their nuclear weapons.

The UN’s meeting, held between April 27 and May 22, was the latest in a set of reviews of the 1970 nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). It did not end well.

Some success but limited

Held every five years, the NPT reviews assess progress made towards a) preventing the proliferation of nuclear weapons; b) enabling states adhering to the treaty to access nuclear technology for peaceful purposes; and c) in moving towards the eventual disarmament of the nuclear weapons held by the P5 states.

The NPT has been remarkably successful in many ways: 191 of the 195 states in the world have signed up, and the treaty’s guiding influence has helped to keep the number of countries acquiring nuclear weapons down to a handful.

Together with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), the NPT has been important in regulating the peaceful use of nuclear technology and strengthening the legal case against weapons proliferation. One hundred and eighty-six states have forsworn any ambition to develop nuclear weapons in exchange for a promise made by the nuclear armed states – under Article VI of the Treaty – that they will eliminate their nuclear arsenals.

But the treaty’s success in achieving this disarmament has been extremely limited.

This is essentially because the P5 states seem wedded to holding on to their arsenals indefinitely, regardless of the fact that the non-nuclear states have kept their end of the bargain.

It was against this acrimonious background that states gathered between April and May at the UN in New York to review progress. Uppermost in the minds of the non-nuclear states was the need for the P5 to take their disarmament obligations seriously, and their frustration towards the nuclear states was palpably evident.

The non-nuclear states had assiduously conducted studies and reports and put together step-by-step processes and action plans designed to lead the nuclear states to disarmament.

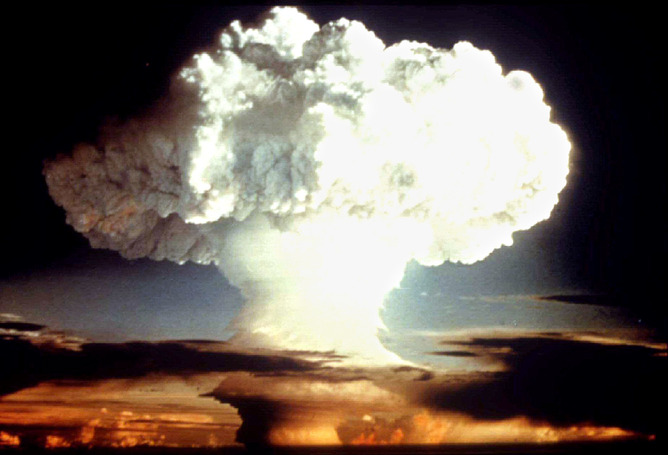

But 45 years after negotiating the NPT and 25 years after the Cold War ended, there are still almost 16,000 nuclear weapons in existence, many of them on hair-trigger alert and far more powerful than the bomb dropped on Hiroshima.

It is an arsenal capable of destroying our world hundreds of times over.

Given this, it was not surprising that last month’s meeting ended with states unable to reach a consensus document. It showed that the majority of states in the world have now given up hope that disarmament can be achieved via the NPT process.

Enduring Risks

But the continued possession of nuclear weapons puts all states in the international system at risk. As the non-nuclear states have pointed out over and over again, and as Australia’s Canberra Commission noted back in 1996, as long as any one state has nuclear weapons, other states will want them too; as long as there are nuclear weapons in existence, there is a strong risk that – sooner or later – they will be used; and any use of nuclear weapons will be catastrophic. We have been fortunate in avoiding a nuclear weapons disaster so far, but there is no guarantee that this luck will hold.

Recent books and reports show just how close we have come to nuclear weapons being used – either deliberately or by accident – and reveal an uncomfortable truth: we cannot remain blasé about this situation and continue to run that appalling risk.

The impasse in New York

The non-nuclear states had long pinned their hopes on Article VI of the NPT, and many other pledges made by the P5 over the years reiterated this obligation. But last month’s stalemate was the straw that seemed to break the camel’s back.

When the US and Britain (supported by Canada) refused to accept the RevCon’s draft final document – even with its watered-down language on disarmament – it was clear that the existing treaty was going nowhere. These states rejected a proposal to hold a conference to address the establishment of a Middle East WMD Free Zone, something that Arab and other non-aligned states had been repeatedly promised over the past twenty years.

Britain, the US and Canada refused to be bound by what they called an “arbitrary” timetable for such a conference. In reality, they were protecting their regional ally, Israel, which is widely known to possess around 80 nuclear weapons and which refuses to sign the Non-Proliferation Treaty.

As the South African head of delegation noted,

“The failure on the Middle East leaves us in a perverse situation [in which] a state that is outside of the Treaty has expectations of us and expects us to play by rules it will not play by and be subjected to scrutiny it will not subject itself to.”

She added that, “there was a sense that the NPT had degenerated into minority rule — as in apartheid-era South Africa — where the will of the few reigned supreme over the majority.”

This was perhaps the most telling indictment of the P5’s failure to disarm, and it drew support from the many NGO and academic delegates gathered at the UN’s General Assembly hall observing the process late into the final evening of the conference.

A new ‘humanitarian initiative’ to ban nuclear weapons

The result of the diplomatic fracture at the NPT conference is that most non-nuclear armed states will now take their cause elsewhere.

Disappointed that the NPT is really only a charade in which the interests of a small but defiant minority (the nuclear armed states) will inevitably prevail, and with no prospect of nuclear disarmament in sight, 107 states have now signed the “humanitarian pledge” to work toward a treaty banning nuclear weapons.

This pledge was initiated by Austria in December 2014, following a series of high-level gatherings that explored what has now come to be called the Humanitarian Impacts of Nuclear Weapons (HINW) project. The failure of the NPT process, evident in New York last month, means that these states consider themselves free to pursue the de-legitimization of nuclear weapons in this way.

And this way, with its emphasis on the humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons, HINW is rapidly gaining support.

From Wikipedia

The HINW project has shown the devastating impact that any use of these weapons will have on human life (with hundreds of thousands, if not millions, killed outright in the most gruesome and cruel way, and with ongoing radiation impacts on future generations); on climate and the environment (where the effects of a nuclear winter are likely to devastate the planet, affecting water resources and food production with up to two billion people facing starvation); and on other aspects of life, leading to a dystopian world barely imaginable to us today.

Not surprisingly, the nuclear armed states (and some US allies) have dismissed the humanitarian approach as a diversion from “serious” efforts to address disarmament.

There are also those who think that the ban-treaty envisaged by the non-nuclear states will not bring about disarmament, because the nuclear states will simply not sign it.

They are right; but this is not necessarily the objective. A treaty banning nuclear weapons will fill the legal gap that currently exists with regard to weapons of mass destruction: both chemical and biological weapons have been successfully banned, but no such ban exists against the most destructive of WMDs, nuclear weapons.

Just as the chemical and biological weapons, and also landmines and cluster munitions, have been outlawed, leading to dramatic reductions in the use of these weapons and an increasing sense that no “civilized” states would use them, so too will a nuclear ban focus on the unacceptable use of nuclear weapons.

In time, and with growing adherence, this ban is likely to be taken seriously by the nuclear weapon states and their allies.

Disarmament may still be a long way off, but at least this new vehicle promises more than the nuclear weapon states in the Non-Proliferation Treaty have been willing to provide. The NPT will continue to exist, as a somewhat hollow five-yearly diplomatic exercise, but there are no illusions now that it can lead to disarmament.

Dispiriting though this might seem, the failed conference now liberates the world to seek safety from nuclear annihilation by other, more promising means. This was the real achievement in New York last month.

![]()

Marianne Hanson is Associate Professor of International Relations at The University of Queensland.

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Read the original article.