Conor Heffernan, The University of Texas at Austin College of Liberal Arts

The cultural obsession with six-pack abdominals shows no signs of abating. And if research into male body image is to be believed, it will likely only grow, thanks to social media.

Today, there’s an entire industry centered on obtaining – and maintaining – chiseled abs. They’re the subject of books and social media posts, while every action movie star seems to sport them. Pressure is also mounting on women to sport six-pack abs as body ideals for athletic women have evolved.

All of this raises the question, when did the six-pack craze start?

It may seem like a relatively recent phenomenon, a byproduct of the fitness culture boom in the 1970s and 1980s, when Arnold Schwarzenegger and Rambo reigned, and men’s muscle mags and aerobics took off.

History proves otherwise. In fact, Western culture’s fascination with chiseled abdominals can be traced to the late 18th and early 19th centuries, when the ideal male body image in the West started to shift.

Greeks inspire envy

While I was researching Irish health and body cultures, I became fascinated with changing male body ideals.

French historian George Vigarello has written about how the ideal male figure and male silhouette shifted in Western society. British and American cultures in the 17th, 18th and, to a certain degree, the 19th centuries valued large or rotund male bodies. The reasons for this were relatively straightforward: Rich men could afford to eat more, and a larger frame was indicative of success.

It was only during the early 19th century that lean and muscular physiques began to be highly coveted. In the space of a few decades, plump bodies came to be seen as slovenly, while lean, athletic or muscular builds were associated with success, self-discipline and even piety.

Part of this transformation stemmed from a renewed European interest in ancient Greece. Kinesiologist Jan Todd and others have written about the impact that ancient Greek imagery and statuary had on body images. In much the same way that social media has distorted body image, artifacts like the Elgin Marbles – a group of sculptures brought to England in the early 1800s whose male figures sport lean and muscular physiques – helped spur interest in male muscularity.

This interest in muscularity deepened as the century progressed. In 1851, a grand commercial and cultural celebration known as the “Great Exhibition” was hosted in London. Outside the exhibit halls were Grecian statues. Writing in 1858 on the impact those statues had, British physical educationalist George Forrest complained that the British “are apparently devoid of that beautiful series of muscles that run round the entire waist, and show to such advantage in the ancient statues.”

Projections of military might

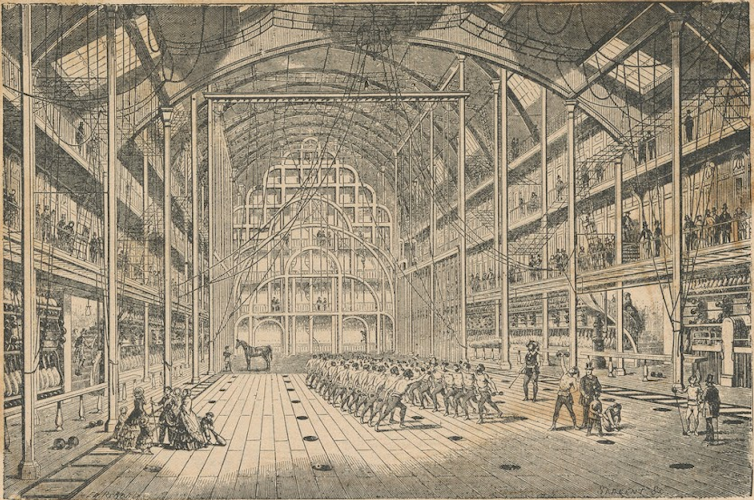

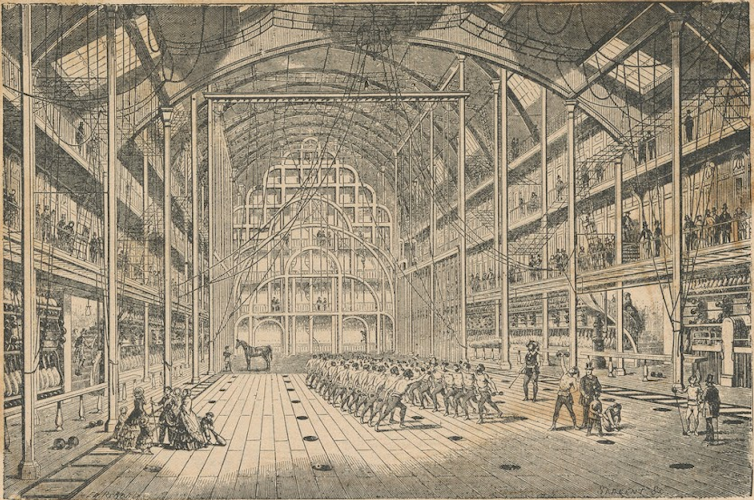

Statues and paintings mattered long before photography came to influence fitness standards in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Equally important, however, was the growth of military gymnastics at the beginning of the century. At the same time that ideal body types for men were changing, so, too, was European society.

As a result of the Napoleonic Wars at the beginning of the 19th century, several gymnastic programs were created to bolster and strengthen young men’s bodies around Europe. French soldiers were renowned for their physical fitness, both in terms of their ability to march for days on end and move quickly in battle. After many European states suffered humiliating defeats at the hands of Napoleon’s forces, they started to take the health of their troops much more seriously.

Gymnast Friedrich Ludwig Jahn, through his Turner system of calisthenic exercises, was tasked with fortifying Prussia’s military strength.

In France, a Spanish gymnastics instructor named Don Francisco Amorós y Ondeano was charged with rebuilding the physique and stamina of French troops, while in England a Swiss fitness instructor named P.H. Clias trained the military and the navy during the 1830s. To accommodate the growing European interest in fitness, bigger and bigger gymnasiums started being built across the continent.

Soldiers weren’t the only ones participating in these programs. For example, Jahn’s Turner system – which promoted the use of parallel bars, rings and the high bar – became one of the most popular exercise programs of the century among members of the European public and went on to gain a following among Americans. Clias, meanwhile, opened classes for middle- and upper-class men, and Amorós y Ondeano – along with other European gymnastics instructors – was regularly quoted in gymnastics texts published from the 1830s onward.

The six-pack industry is born

So the seeds for modern six-pack mania were planted in two ways: First, men started eyeing Greek statues with envy. Then they developed the means to sculpt their bodies in those statues’ images. Meanwhile, writers from the 1830s and 1840s prodded men to aspire to svelte bodies, strong trunks and no excess body fat.

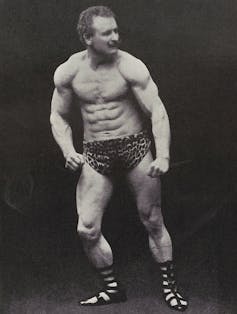

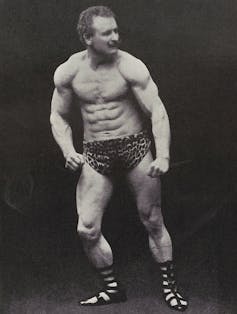

But the obsession with six-packs truly blossomed in the early 1900s. By then, strongmen like Eugen Sandow were able to build off the existing interest in Greek imagery and gymnastics by using photography, cheap mail postage and the new science of nutritional supplements to cash in on the longing for the perfect body.

Sandow himself sold books, exercise equipment, nutritional supplements, children’s toys, corsets, cigars and cocoa. Sandow, who was once hailed as the “world’s most perfectly developed specimen,” inspired countless men to shed excess “flesh” – the term given for body fat – to show off their abdominals. Abdominals, incidentally, was always the term used at this time.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

It wasn’t until the late 1980s and early 1990s that getting a “six pack” referred not just to cans of beer and started serving as a stand-in for visible abdominal muscles. Searching through Google Ngram shows that from the mid-to-late 1990s the term’s popularity grew exponentially.

“Six-pack abs” quickly became parlance thanks to ingenious marketers determined to sell a range “get fit fast” devices, from Abs of Steel to 6-Minute Abs.

Few have stood the test of time. Yet the longing for the coveted six-pack – as the more than 12 million Instagram posts with the #sixpack hashtag can attest – endures.

Conor Heffernan, Assistant Professor of Physical Culture and Sport Studies, The University of Texas at Austin College of Liberal Arts

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Conor Heffernan, The University of Texas at Austin College of Liberal Arts

The cultural obsession with six-pack abdominals shows no signs of abating. And if research into male body image is to be believed, it will likely only grow, thanks to social media.

Today, there’s an entire industry centered on obtaining – and maintaining – chiseled abs. They’re the subject of books and social media posts, while every action movie star seems to sport them. Pressure is also mounting on women to sport six-pack abs as body ideals for athletic women have evolved.

All of this raises the question, when did the six-pack craze start?

It may seem like a relatively recent phenomenon, a byproduct of the fitness culture boom in the 1970s and 1980s, when Arnold Schwarzenegger and Rambo reigned, and men’s muscle mags and aerobics took off.

History proves otherwise. In fact, Western culture’s fascination with chiseled abdominals can be traced to the late 18th and early 19th centuries, when the ideal male body image in the West started to shift.

Greeks inspire envy

While I was researching Irish health and body cultures, I became fascinated with changing male body ideals.

French historian George Vigarello has written about how the ideal male figure and male silhouette shifted in Western society. British and American cultures in the 17th, 18th and, to a certain degree, the 19th centuries valued large or rotund male bodies. The reasons for this were relatively straightforward: Rich men could afford to eat more, and a larger frame was indicative of success.

It was only during the early 19th century that lean and muscular physiques began to be highly coveted. In the space of a few decades, plump bodies came to be seen as slovenly, while lean, athletic or muscular builds were associated with success, self-discipline and even piety.

Part of this transformation stemmed from a renewed European interest in ancient Greece. Kinesiologist Jan Todd and others have written about the impact that ancient Greek imagery and statuary had on body images. In much the same way that social media has distorted body image, artifacts like the Elgin Marbles – a group of sculptures brought to England in the early 1800s whose male figures sport lean and muscular physiques – helped spur interest in male muscularity.

This interest in muscularity deepened as the century progressed. In 1851, a grand commercial and cultural celebration known as the “Great Exhibition” was hosted in London. Outside the exhibit halls were Grecian statues. Writing in 1858 on the impact those statues had, British physical educationalist George Forrest complained that the British “are apparently devoid of that beautiful series of muscles that run round the entire waist, and show to such advantage in the ancient statues.”

Projections of military might

Statues and paintings mattered long before photography came to influence fitness standards in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Equally important, however, was the growth of military gymnastics at the beginning of the century. At the same time that ideal body types for men were changing, so, too, was European society.

As a result of the Napoleonic Wars at the beginning of the 19th century, several gymnastic programs were created to bolster and strengthen young men’s bodies around Europe. French soldiers were renowned for their physical fitness, both in terms of their ability to march for days on end and move quickly in battle. After many European states suffered humiliating defeats at the hands of Napoleon’s forces, they started to take the health of their troops much more seriously.

Gymnast Friedrich Ludwig Jahn, through his Turner system of calisthenic exercises, was tasked with fortifying Prussia’s military strength.

In France, a Spanish gymnastics instructor named Don Francisco Amorós y Ondeano was charged with rebuilding the physique and stamina of French troops, while in England a Swiss fitness instructor named P.H. Clias trained the military and the navy during the 1830s. To accommodate the growing European interest in fitness, bigger and bigger gymnasiums started being built across the continent.

Soldiers weren’t the only ones participating in these programs. For example, Jahn’s Turner system – which promoted the use of parallel bars, rings and the high bar – became one of the most popular exercise programs of the century among members of the European public and went on to gain a following among Americans. Clias, meanwhile, opened classes for middle- and upper-class men, and Amorós y Ondeano – along with other European gymnastics instructors – was regularly quoted in gymnastics texts published from the 1830s onward.

The six-pack industry is born

So the seeds for modern six-pack mania were planted in two ways: First, men started eyeing Greek statues with envy. Then they developed the means to sculpt their bodies in those statues’ images. Meanwhile, writers from the 1830s and 1840s prodded men to aspire to svelte bodies, strong trunks and no excess body fat.

But the obsession with six-packs truly blossomed in the early 1900s. By then, strongmen like Eugen Sandow were able to build off the existing interest in Greek imagery and gymnastics by using photography, cheap mail postage and the new science of nutritional supplements to cash in on the longing for the perfect body.

Sandow himself sold books, exercise equipment, nutritional supplements, children’s toys, corsets, cigars and cocoa. Sandow, who was once hailed as the “world’s most perfectly developed specimen,” inspired countless men to shed excess “flesh” – the term given for body fat – to show off their abdominals. Abdominals, incidentally, was always the term used at this time.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

It wasn’t until the late 1980s and early 1990s that getting a “six pack” referred not just to cans of beer and started serving as a stand-in for visible abdominal muscles. Searching through Google Ngram shows that from the mid-to-late 1990s the term’s popularity grew exponentially.

“Six-pack abs” quickly became parlance thanks to ingenious marketers determined to sell a range “get fit fast” devices, from Abs of Steel to 6-Minute Abs.

Few have stood the test of time. Yet the longing for the coveted six-pack – as the more than 12 million Instagram posts with the #sixpack hashtag can attest – endures.

Conor Heffernan, Assistant Professor of Physical Culture and Sport Studies, The University of Texas at Austin College of Liberal Arts

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.