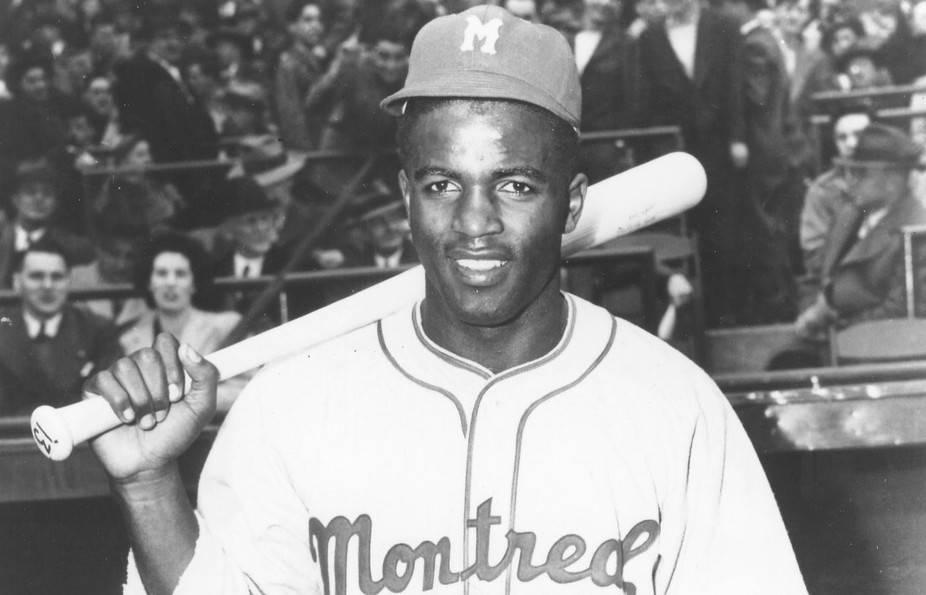

In a state wrought with racial tension, Jackie Robinson suited up for his first spring training game

Chris Lamb, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis

Seventy years ago, on the morning of March 17, 1946, Jackie Robinson sat with his wife Rachel in a small bedroom in a stranger’s home in Daytona Beach, Florida, and wondered what lay ahead for him that afternoon.

Robinson would make history if he played for the Triple A Montreal Royals in his first spring training game. No black had worn the uniform of a team in organized baseball since the 19th century.

The Royals were scheduled to play their parent club, the Brooklyn Dodgers, and Jackie and Rachel didn’t know if he would even be allowed to take the field at segregated City Island Ball Park. What would happen if he did play? What would white fans yell at him, throw things at him – or worse? He knew that any black who challenged segregation in the South was putting his life in danger.

Much has been written about Robinson’s first game in the major leagues for the Brooklyn Dodgers on April 15, 1947. Far less is known about the spring of 1946, when the ballplayer was competing for a spot on the Dodgers’ top farm club. Rarely has an athlete found himself under more pressure in such hostile conditions as Robinson did in Florida.

Stepping into dangerous territory

The first integrated spring training game took place two years before President Truman desegregated the U.S. Army, eight years before the U.S. Supreme Court desegregated schools, and 18 years before Congress passed the Civil Rights Act that outlawed all racial discrimination.

In the post-World War II South, racial tensions were especially high.

A month earlier, a South Carolina police officer had beaten a recently discharged Army sergeant named Isaac Woodard, blinding him. At the end of February, a race riot in Columbia, Tennessee left two blacks dead, 100 jailed and the segregated section of town ravaged by a white mob.

A white newspaper editor in Virginia warned that any attempt to change segregation laws would leave “hundreds, if not thousands, killed and amicable race relations set back for decades.” And no state was more dangerous for blacks than Florida.

The Montreal Royals announced they had signed Robinson the previous fall. But a roster spot was not assured. Like any other prospect, he would have to play well during spring training to make the team. The team later signed a second black player, Johnny Wright, who accompanied Robinson during spring training.

The pressure builds

When Jackie and Rachel left their home in Los Angeles for Daytona Beach on February 28, they’d been married for only two weeks. The trip took almost two days. They were twice bumped from planes and replaced with white passengers. They had to take a bus across the state of Florida from Pensacola to Jacksonville. When the Robinsons settled into their seats, the driver, calling Jackie “boy,” ordered the couple to the back of the bus.

Daytona Beach did not have enough ballfields to accommodate the hundreds of players – many of them war veterans – who tried out for one of the many teams in the organization. Rickey assigned Montreal to train in Sanford, 40 miles to the southwest, until enough players were cut and all the teams could train in Daytona Beach.

But after the team’s second day of practice in Sanford, a white man told black journalists that 100 or so townspeople would take matters into their hands if Robinson and Wright were not “out of town by nightfall.”

The ballplayers immediately returned to Daytona Beach, where the Montreal team practiced at Kelly Field in the black section of the city. The Robinsons and Johnny Wright stayed with black families while the white players stayed in an oceanfront hotel.

Robinson tried to impress his coaches by throwing the ball as hard as he could, leaving him with a sore arm. His hitting produced one weak grounder after another.

Robinson admitted to Pittsburgh Courier sportswriter Wendell Smith that he was trying so hard because he did not want to let down the blacks who, he thought, were depending on him.

I could hear them shouting in the stands, and I wanted to produce so much that I was tense and over-anxious. I found myself swinging hard enough to break my back. I started swinging at bad balls and doing a lot of things I wouldn’t have done under ordinary circumstances. I wanted to get a hit for them because they were pulling so hard for me.

Branch Rickey, the president of the Brooklyn Dodgers who had signed Robinson on October 23, 1945, persuaded city officials to allow Robinson to play in the game between the Royals and the Dodgers. Rickey insisted that he was interested only in integrating baseball and not in desegregating the South.

Blacks saw things differently. Roy Wilkins, the editor of the NAACP’s magazine The Crisis, told the Amsterdam News that the signing of Robinson meant that blacks “should have their own rights, should have jobs, decent homes and education, freedom from insult, and equality of opportunity.”

In the hours before the 3 p.m. game, black ministers in Daytona Beach asked their congregations to pray for Robinson, Hundreds of blacks walked to the ballpark in their Sunday clothes. Mothers and fathers held their children’s hands, while some broke away and ran ahead to the turnstiles. Long before the game began, it was clear that the ballpark’s segregated bleachers down the right field line would be inadequate for all the black spectators who wanted to see Robinson.

Batter up!

Robinson batted for the first time in the second inning and braced himself for an assault of racial epithets. “This is where you’re going to get it,” he told himself as he walked to the plate.

Robinson heard the loud applause from the right-field bleachers. There was some booing from white spectators but also scattered applause.

He heard one voice in particular: “Come on, black boy! You can make the grade!” Another white spectator yelled, “They’re giving you a chance – now come on and do something.”

In his three at-bats, Robinson fouled out twice and hit into a fielder’s choice. He was disappointed in his hitting but encouraged by what he heard.

“I knew, of course, that everybody wasn’t pulling for me to make good, but I was sure now that the whole world wasn’t lined up against me,” Robinson wrote in his 1948 autobiography. “When I went to sleep, the applause was still ringing in my ears.”

Daytona Beach would be the only city that let Robinson play that spring. When the Royals went to Jacksonville, they found the stadium padlocked. Deland canceled a day game because the lights weren’t working. When the Royals returned to Sanford, the game started without incident. But after Robinson scored a run, a police officer was waiting for him and ordered him off the field.

As the days passed, Robinson’s arm healed and his hitting improved. By the end of the spring, he learned he had made the Royals team. In the first game of the International League season, Robinson had four hits, including a home run. He led the Montreal team to the league championship and signed with the Dodgers the following spring.

Today, a statue of Robinson stands outside what used to be City Island Ball Park. It’s now called Jackie Robinson Ballpark.

Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

Chris Lamb is the author of Blackout: The Untold Story of Jackie Robinson’s First Spring Training.

![]()

Chris Lamb, Professor of Journalism, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.